“Before you can write a good plot, you need to write a good place,” says the Swedish novelist Linn Ullman. Writing well about places is a skill required not only by novelists, but also by travel writers and all those who want to communicate their enthusiasm about the diversity and similarities of places.

Ullman, the daughter of Ingmar Bergman, considers her own life as “somewhat placeless” because she grew up in so many different places. But she thinks that precisely because of this she likes authors who are very place oriented. She admires Canadian Nobel prize-winning author Alice Munro, and specifically a comment Munro wrote in her story Face: “Something had happened here. In your life there are a few places, or maybe only one place, where something has happened. And then there are the other places, which are just other places.” (This illustration is from the Atlantic Monthly article about Linn Ullman)

Ullman, the daughter of Ingmar Bergman, considers her own life as “somewhat placeless” because she grew up in so many different places. But she thinks that precisely because of this she likes authors who are very place oriented. She admires Canadian Nobel prize-winning author Alice Munro, and specifically a comment Munro wrote in her story Face: “Something had happened here. In your life there are a few places, or maybe only one place, where something has happened. And then there are the other places, which are just other places.” (This illustration is from the Atlantic Monthly article about Linn Ullman)

Munro’s stories are set in small communities in southern Ontario, where whole worlds play out. Every story has to happen somewhere. You do not have a story of life without an actual place, Ullman declares. “You can’t separate one from the other.”

It isn’t easy to write place

If you start off trying to write a general, all-embracing account of a somewhere without any clear sense of how to do it, you will probably either grind to a frustrating halt or end up with a sterile inventory that conveys nothing of the place’s identity. To write effectively about a place you have to find a hook, an entry point. Robert Pirsig in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, which is an account of a search for quality in things he encounters as he makes his way across America on a motorbike, provided a simple example I often think about. Somewhere along his way, perhaps in Montana, he took a teaching job, and asked his students to write a short essay about the qualities of the town they live in. One soon comes back and tells him: “I can’t do this. I don’t know where to start.” Pirsig suggests writing about the main street. Back comes the student a day later and says: “I still can’t begin.” Pirsig says: “Write about the stones in the wall of city hall.” A few days later the student tells him: “It’s amazing. Now I can’t stop writing.”

A sign with important advice at a State Park in Montana, 1998.

Finding hooks isn’t easy. Not because they are obscure, but because most of us are not used to looking carefully and thoughtfully at the world around us, and noticing the significance that lies in details. To write well about places (or to photograph them) you first have to be able to see them clearly. In effect that means reading their landscapes with a critical eye. This is easy to say but actually requires an effort to overcome a tendency to ignore places that are inconspicuous because they are so familiar, and also to overcome deeply ingrained habits of seeing things according to conventional categories about what is pretty or ugly or important

Two Guides for Reading Landscape and Place

I know two useful guides for reading landscape and place in this critical way. One is a website How to Read a Landscape that was prepared in 2008 for of a course taught by William Cronon, an environmental historian at the University of Wisconsin. The course is oriented towards historical research, and pays homage to Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac, which was written about a nearby region in Wisconsin. For Cronon landscapes, both rural and urban, are documents that contain invaluable historical and environmental information for those who know to decipher and interpret it. Although Cronon’s website claims that it is not intended as a comprehensive guide, it does consist mostly of very practical suggestions from the students who participated in the course. These range from advice about the equipment needed to start making observations of somewhere, to suggestions about unpacking layers of meaning and the relationships between modes of production and consumption. Landscapes are clues to culture, to borrow a phrase from the geographer Peirce Lewis in his essay “Axioms for Reading the Landscape.” They are what a culture makes for itself rather than what it says about itself and are therefore honest statements about cultural values.

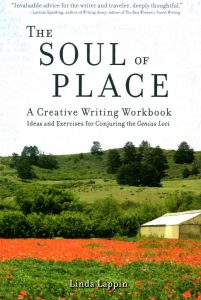

The other guide is Linda Lappin’s 2015 book The Soul of Place: A Creative Writing Workbook – Ideas and Exercises for Conjuring the Genius Loci. She is a novelist and teacher, and her orientations are towards creative and travel writing. Her book offers a number of exercises for recognizing and writing about genius loci and what she calls the personal geography of places. Lappin offers many questions that can be asked of a place – for instance: how might the natural resources and climatic conditions affect the livelihoods of the people? What color is the light? What succeeds in creating a sense of intimacy? How does it feel underfoot? How do authorities reveal themselves? And she proposes a number of short writing exercises that can attempt to answer these sorts of questions. She also suggests many possible foci (which I called hooks above) for writing about a place, for instance, a bridge, a bus station, a door, a parking area, a laundromat, a shopping mall, a tree, stairs, traffic in motion, where a saint has died. A well-chosen focus can be a microcosm for the identity of the place.

The other guide is Linda Lappin’s 2015 book The Soul of Place: A Creative Writing Workbook – Ideas and Exercises for Conjuring the Genius Loci. She is a novelist and teacher, and her orientations are towards creative and travel writing. Her book offers a number of exercises for recognizing and writing about genius loci and what she calls the personal geography of places. Lappin offers many questions that can be asked of a place – for instance: how might the natural resources and climatic conditions affect the livelihoods of the people? What color is the light? What succeeds in creating a sense of intimacy? How does it feel underfoot? How do authorities reveal themselves? And she proposes a number of short writing exercises that can attempt to answer these sorts of questions. She also suggests many possible foci (which I called hooks above) for writing about a place, for instance, a bridge, a bus station, a door, a parking area, a laundromat, a shopping mall, a tree, stairs, traffic in motion, where a saint has died. A well-chosen focus can be a microcosm for the identity of the place.

Lappin also discusses what she calls the house of the self, the importance of the picturesque and the sublime, and both postcards and tweets as ways of conveying genius loci. However, for me her most substantial advice is about “Reading the Landscape.” She stresses the importance of identifying patterns and textures, ways of finding images to convey the impressions landscapes have on you, looking for evocative suggestions in place names, and William Least Heat Moon’s idea of “deep maps.” By deep map he means an intensive vertical examination of one place (in his case it is the region around the geographical center of the USA, which is in Kansas), in all its manifestations of genius loci, all its histories and stories and imaginative possibilities.

A store in Washington D.C. that blends writing and place.

Seeing, Thinking and Describing Places

I indicated some of my own thoughts about reading landscape some years ago in an essay “Seeing, Thinking, Describing Landscapes” (available online at Academia.edu). While I emphasized the importance of seeing clearly, albeit in a much briefer and more abstract way than Lappin and Cronon, my main point was that seeing, thinking and describing/writing are activities that reinforce one another, often through a series of iterations. They involve what the Victorian art critic John Ruskin described as “a curiously balanced condition of the powers of the mind.” In other words, seeing clearly involves thinking carefully, responding to patterns in what has been seen, relating observations to theory, reading what others have written, and finding effective language to express your interpretations and observations. Indeed the intention of writing will inevitably direct attention towards certain aspects of a place depending on whether the aim is prepare a planning report, a short story or a travel blog. Moreover the act of writing will often reveal shortcomings in thoughts and observations that have to filled by going back to look again from a different perspective.

Final Comments

Every story has to happen somewhere. I believe the exercises in Lappin’s The Soul of Place, and the suggestions in Cronon’s website, are excellent foundations for learning to read and then write about places and their landscapes. To follow every step they propose would, however, be very challenging. I find it easier to pick and chose from the types of questions and hints they offer, and to allow these to challenge my habits of thinking and to help me to see with what Goethe called “clear fresh eyes.”

NOTE: I see similarities between learning to read landscapes and learning to draw as it has been proposed by Kimon Nikolaides in The Natural Way to Draw and Betty Edwards in Drawing with the Right Side of the Brain. The gist of their argument is that anyone who can use a pencil to write has the motor skills needed to draw well; what most of us lack is the ability to observe carefully. If you can see well, you can draw well, and they both offer sequences of exercises that facilitate drawing well through seeing well. Nikolaides thought it might take months to achieve substantial results, but Edwards shows more encouragingly that for some people a breakthrough can happen with only five days of focused effort.

NOTE: I see similarities between learning to read landscapes and learning to draw as it has been proposed by Kimon Nikolaides in The Natural Way to Draw and Betty Edwards in Drawing with the Right Side of the Brain. The gist of their argument is that anyone who can use a pencil to write has the motor skills needed to draw well; what most of us lack is the ability to observe carefully. If you can see well, you can draw well, and they both offer sequences of exercises that facilitate drawing well through seeing well. Nikolaides thought it might take months to achieve substantial results, but Edwards shows more encouragingly that for some people a breakthrough can happen with only five days of focused effort.

References and an acknowledgement:

Edwards, Betty 1989 Drawing with the Right Side of the Brain

Fassler, Joe 2014 “Before you can write a good plot, you need to write a good place” An interview with Linn Ullman, Atlantic Monthly April 2014 available online here

Goethe, J.D 1970 (1786-88) Italian Journey (trans W.H. Auden and E. Mayer) (Penguin)

Lappin, Linda 2015 The Soul of Place: A Creative Writing Workbook – Ideas and Exercises for Conjuring the Genius Loci. Palo Alto: Travelers’ Tales

Lewis, Peirce, 1979 “Axioms for Reading Landscape” in Don Meinig (ed) The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes, Oxford University Press

Nikolaides, Kimon, 1941 The Natural Way to Draw, Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Pirsig, Robert 1974 Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Relph, Edward 1984 “Seeing, Thinking and Describing Landscape” in Environment, Perception and Behavior, eds. T. Saarinen, D.Seamon and J. Sell, University of Chicago, Department of Geography Research Series, No. 209, pp.209-223. Available here at academia.edu.

Ruskin, John, 1843 Modern Painters Vol III, Chapter 17, Section 5

And my thanks to Linda Lappin who generously sent me a copy of her fascinating book which has got me reading landscapes in all sorts of new ways.