A Dread of Certain Places and other Negative Responses to Place

Topophobia is defined in the OED as a morbid dread of certain places. From a medical perspective it is regarded as an anxiety disorder. I have no idea how common this is, but apparently in extreme cases it can warrant psychiatric treatment.

My understanding is that has a much broader meaning than this. I first wrote about it in 1976 (in an obscure discussion paper: “The phenomenological foundations of geography,” University of Toronto, Department of Geography, Discussion Paper No 21, 1976; available at Academia.edu), in which I suggested that the components of topophilia, such as environments of persistent appeal, the pleasure gained from direct encounters with nature, or knowing places through good health and health and familiarity, all have a topophobic equivalent. Topophilia involves positive affective bonds between human beings and environments; topophobia refers to the dislike or fear of places, and includes all the negative emotional responses people have to spaces, places, and landscapes that they find distasteful or frightening. Think of Mirkwood in The Lord of the Rings. To put it succinctly, topophilia is about pleasant experiences of places, and topophobia is about the nasty experiences.

An army base near Lago de Atitlan, Guatemala in 1998, shortly after the end of a civil war in which the army had razed entire villages. The cute sentry post belies the deep topophobia inherent both in those actions and in the reactions of survivors to this particular place fragment.

Diverse Manifestations of Topophobia

Most negative language about place – for instance placelessness, non-places, dislocation, uprooting, dystopia, displacement, delocalization, disembedding – has to do with processes that have suppressed or undermined positive place experiences. Some of these are primarily about loss of topophilia, but others involve topophobia because a once pleasant place has become abhorrent. This was the case with uprooting during the Dust Bowl, or the “landscapes of death” in north-east Brazil described by Josue de Castro in his book Death in the North-East, (Random House, 1966).

But topophobia has to do with more than loss of place. In my 1976 essay I cited an article about the coal-mining districts of Appalachia, a region where it had been estimated that 50% of the population suffered from depression, compared to about 4% in the United States. A local doctor explained: “I feel depressed here myself just from the ways things look. That includes the roads, housing, everything.” (C. McCarthy, “Whose Who in Appalachia” Atlantic Monthly, July 1976). Something similar could probably be said about the impoverished settlements on reserves of aboriginal peoples in northern Canada, about ghettoes of social housing in high rise apartments, about the devastated cities of Syria. In such cases the ugliness of the place itself, the everyday challenges of surviving there, and the depression and anxiety of inhabitants, seem to reinforce one another in a vicious cycle.

A B movie with the name of the song. A good movie with the same theme is The Last Picture Show, with Jeff Bridges and Cloris Leachman, 1971.

Many experiences of places are far from agreeable, for reasons that have to do with our moods, environmental events, or the character of the setting. If you happen to be depressed or upset for some reason, landscapes will not appear cheerful. Experiences of the natural environment, so often benign and pleasant, can be filled with anxiety and even panic as the weather worsens, tornado warnings sound, a brush fire approaches, the drought intensifies, the earthquake happens. In cities we avoid urban neighbourhoods that are dangerous because they are gang territories, or simply because they are unfamiliar and seem threatening. An isolated place, caught in drudgery, far from the centres of fashion, lacking any sense of possible change or opportunities for personal growth, is stultifying for most young people. The places of childhood and home are rejected as intolerable burdens; the priority is to get away. This sentiment was captured perfectly in the song”We Gotta Get out of this Place” by Eric Burdon and The Animals, released in 1965. It is a theme in numerous movies and novels.

Topophobia can be aesthetic, such as a dislike of modernist buildings or graffiti. It can opinionated and intellectual, for instance in the attitude that stands behind condemnations of urban sprawl and suburbs. It can be physiological; a former student of mine suffered migraines whenever she went into an enclosed shopping mall. Or ideological; one of my uncles refused to go into the great country houses of England because he considered them manifestations of decadence and oppression. The forms of topophobia are no less diverse than those of topophilia, though academics and artists pay much less attention to them.

Paradoxical Topophobia

Because topophobia, like topophilia, is associated both with the personality of places and with our attitudes, our experiences can switch from topophilic to topophobic, and vice versa, as our moods change and as the place itself changes. The desire of those young people who got out of the places where they grew up – the small towns and farms and slums is often transformed later in life into nostalgia about them.

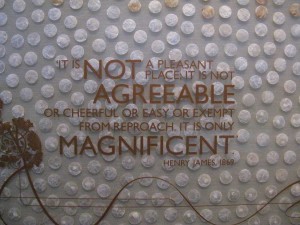

This poster with a paradoxical topophobic/topophilic quote from Henry James about London, is in the London Museum.

Indeed it seems to be possible, if somewhat paradoxical, that in some circumstances positive and negative reactions to a place can be held almost simultaneously. Beatriz Munoz-Gonzalez has a paper titled “Topophilia and Topophobia: The Home as an Evocative Place of Contradictory Emotions” (Space and Culture, May 2005), in which she considers how home in south-west Spain is place of both satisfaction and dissatisfaction, somewhere for belonging and creation, yet also a prison and place of conflict. The very term “domestic violence” captures this contradiction succinctly. (I expect to explore this contradiction more when I write a post about “Home and Place.”)

Knowing more about topophobia as a means of avoiding where we don’t want to be.

A group of musicians, dancers and electronic artists organizing performance events in London has adopted the name “LondonTopophobia.” They use trepidation and confusion about places to raise the existential question of how we find our place in the world. If I understand their intention correctly, their aim is to convey the idea that we end up where we are in part by avoiding where we don’t want to be. A related publication on Topophobia and the fear of place in contemporary art describes some of these performance events, which include making a video that treats an urban wasteland as a spectacle, a “filmic pan” of the aftermath of a car accident, a depiction by a Finnish/Sami artist of her sense of being out of place, and an imaginary journey in virtual space.

To my knowledge there has been no study of topophobia that is an equivalent to Tuan’s account of topophilia. In some respects this is not altogether surprising because most people writing about place, or painting and photographing places, have chosen to illustrate their nice qualities, and place is treated as an aspect of belonging and a source of pleasure. Topophobia is about the dark side of environmental experience, and because it is, like topophilia, not the strongest of human emotions it is quite easily pushed aside, avoided or ignored, so that we can turn our attention to nicer experiences. Nevertheless, I think it would be very helpful to know more about why we avoid where we don’t want to be.

Finally, a Google search turned up two images of Topophobia, the one on the left to illustrate a show of works of the LondonTopophobia group, the more compelling one on the right from a website called Polyvore, which seems to be about fashion or something I cannot quite grasp.