In a previous post I discussed ideas that the power of place is intrinsic and somehow waiting for us to discover it. This is half the story. John Agnew and James Duncan in the preface to their 1989 book The Power of Place: Bringing together geographical and sociological imaginations say their intention was to raise interest in the notion of place as a medium of political and economic power. The implication of this intention is that power is created, given to or ascribed to places because places are produced and not merely pre-ordained locations. In other words, places serve as vehicles to express human powers and status. Versions of this happen on a range of spatial scales from the home to the nation, and the process of ascribing power can be from the bottom up through community action, or from the top down through as a demonstration of the authority of those who are politically and economically dominant.

Power Ascribed to Small Places

Dennis Saleebey in a 2004 paper on “The Power of Place” has written convincingly of “the power of small” for understanding person-environment relations in his discipline of social work. And he lists what he means by small: “rooms, apartments, office cubicles, gardens, cars, atria, hallways, city blocks, cells, classrooms, restaurants, bars, neighbourhood stores, and the like.” These small places are powerful because they affect us directly in various ways depending on the number of people occupying them, the level of stimulation (noises, colour, clutter), and the meanings of things such as pictures and furniture. A very specific example of the power of small places is the 2003 phenomenological study in the journal Midwifery on the Power of Place, which investigates the power that place holds over post-natal experiences of women. Not surprisingly this study concluded that women giving birth in hospitals experienced various degrees of alienation and disempowerment, while the familiar territory of home offered feelings of support, security and control. In the latter case the home place had a quality of positive power associated with having been lived in, whereas in the former the power of place was experienced as impersonal and bureaucratic.

Two examples of the power of small places. Grenoble Day Care is in Flemingdon Park in Toronto. Ourplace (the name is on the green poster) is an non-profit that provides simple transition accommodation for the homeless in Victoria, British Columbia.

A very different idea of the quality of power ascribed to small places was also at the basis of a survey and report titled The Power of Place: The Office Renaissance, commissioned in 2014 by Steelcase, an office furniture company. This concluded that, in the context of changing business practices, office spaces need to be reimagined in order to promote better employee engagement and retention, and that this could be achieved by creating a palette of places in open plan offices that augment people’s interactions with each other while providing access to resources that can only found at work. Of course, Steelcase can provide the advice and furniture needed to achieve this. In other words, better office places are powerful because they promote productivity.

Sign at a conference in Vancouver sponsored by Project for Public Spaces, 2016

Creating the Power of Place in Public Spaces

At a slightly larger and public scale, the Project for Public Spaces, an American organization devoted to placemaking through the careful design of small urban spaces, has suggested that the power of place can be invoked as a solution to unsustainable development trends of the last 75 years. The argument is that power of place can be created through approaches to placemaking that include appropriate combinations urban design, smart growth, walkability, public transportation and local food. The PPS website claims grandly: “ In fact, we can reinvent entire regions starting from the heart of local communities and building outwards.” This seems unlikely, but there is ample evidence that well-designed small urban places, including the work of PPS and urban designers such as Jan Gehl, do have the power to enliven and generate community pride of place in parts of cities that were previously moribund.

Ascribing Power to Place as an Affirmation of Community Identity

Dolores Hayden’s 1995 book on The Power of Place is an account of a different type of placemaking project, one that is more about the validation of community than urban design. It involved the creation of a non-profit in downtown Los Angeles that brought together historians, planners, artists and community members to record local history not as a conventional chronology but specifically in terms of how relatively disadvantaged African American, Latino and Asian American families had experienced it in the course their everyday lives. This history, which otherwise would have been largely undocumented, was then installed in the urban landscape through memorials and artworks, thereby simultaneously affirming the important contribution of these communities to the history of the place where they lived and reinforcing their sense of belonging to that place.

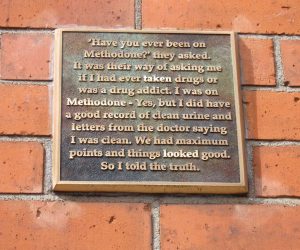

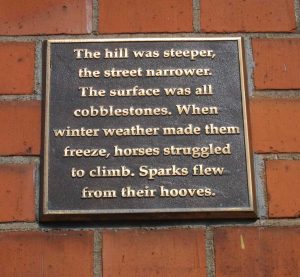

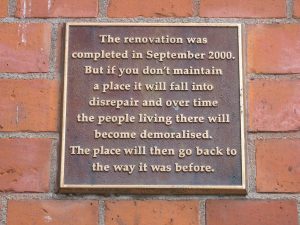

Plaques on the wall of renovated social housing in Dublin (top left) illustrate ways of ascribing power of place and responsibility to the community and its individuals.

The importance of community identity is also demonstrated in a permanent exhibition at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington D.C titled The Power of Place. The aim is to demonstrate the ways in which people have made places even as those places have changed the people in them. The places highlighted, which include Chicago, Tulsa in Oklahoma, Greenville Mississippi and the Bronx in New York, are powerful for African Americans because they are sites of individual and political struggles, and of cultural creativity. They are places where individual and community identities have been created, tested and shaped over time.

A Canadian research report Connecting the Power of People to the Power of Place offers a more academic argument to support community planning. It proposes that most people care deeply about local housing quality, transit connections, walkability and the overall quality of life in their place. It then connects these important everyday concerns with what it calls “the power of the neighbourhood” through which people can begin to work together in community organizations in order to make changes. In this sense, as in Hayden’s project and the Smithsonian exhibit, the power of place consists simultaneously in the fact that place is the shared locus of community concerns, and in the fact that place can serve as the foundation for local political actions for communities that are relatively powerless.

Place as a Production and Expression of Political Power.

At the other end of the political power spectrum the power of place operates differently. It uses specific places to impress and regulate societies. An indication of this is offered by Richard White and John Findlay (1999) in their edited book Power and Place in the North American West, where they define power as the ability of an agent, whether a person, corporation or state, to influence others or natural forces according to the agent’s will. Place, they suggest, is a spatial reality that is constructed or produced, and from this perspective it is therefore an expression of control, authority and the exercise of power through some combination of force, persuasion and manipulation. It follows that if places are produced, then they are expressions of the power of those who produced them.

The best account I know of how political power is ascribed to and presented through places is David Rollason’s 2016 book The Power of Place: Rulers and their palaces, landscapes, cities and holy places. In this he describes and illustrates with photos the messages of power in places that were created by emperors and kings from the early Roman Empire to the early 16th century. Their power was dramatically expressed in several different ways, the most obvious of which were great stone or brick palaces with extravagant furnishings. It was also conveyed by the construction of artificial landscapes of gardens, parks and forests around those palaces, and even more grandly by founding or enlarging cities that were patronized by rulers. In addition, palaces were turned into sacred sites by endowing them with holy buildings or holy objects, and monuments and memorials marked those places where rulers were inaugurated into office, or where their remains were buried.

Vaux le Vicomte, a chateau near Paris with extensive landscaped gardens, is a precursor to Versailles. It was constructed in the late 17th century as a palace and garden for Nicolas Fouquet, the superintendent of finances for Louis XIV, and its grandeur and scale make an impressive display of political power.

Political power was displayed through places in a variety of different ways. Some of it involved a personal display of grandeur and opulence as a way to awe citizens and ambassadors and visitors. Some of it was oppressive, as manifest in forts, castles and city walls, all of which served as ways to subdue and control ordinary people while simultaneously providing security from outside enemies. Some of it was bureaucratic, through the creation of impersonal laws and the institutions to administer them. Some of it was manipulative, building circuses and amphitheatres, or creating popular festivals. Some of it was ideological, merging political power with existing or new religious beliefs, and then persuading citizens and subjects to adopt these beliefs.

Rollason’s book is a history, but it is not difficult to find similarities in present-day displays of the political power of place. In the modern developed world much of this power is bureaucratic. Nevertheless political authority is often displayed in places that have a combination of distinctive architecture and generously landscaped spaces, such as the Capitol and Mall in Washington D.C., which, as the photo on the left suggests, has similar basic elements to convey political power as Vaux le Vicomte – a grand building and extensive artificial landscape. The main differences are that the Capitol is not an opulent private residence but a building for an elected Congress, and the Mall is a public space not a private one. The Mall is also a site for nationally symbolic monuments, such as the Washington monument and the Vietnam war memorial. Many municipalities demonstrate their political authority in similar ways on a smaller scale, with city halls designed by more or less famous architects fronted by a public square where citizens can gather on special occasions. At the state and municipal levels bureaucratic power is subtly revealed through such things as standardized highway design, and signage in parks.

Toronto City Hall expresses municipal political power in its spectacular design of two curving towers embracing the council chamber (the disc object) hovering above a podium where the Mayor and councillors can stand for ceremonies, and its large public square, here being used for a celebration of the South Asian community. The photo on the right shows the view from the podium on a day when the square is not in use for an event. Compare this use of space with that of the bank towers in the financial district, shown below, which aim to maximize the economic value of the real estate they occupy by covering most of it with rectangular buildings on rectangular lots that aim to maximise the economic use of expensive real estate . The political power of place is often demonstrated by a rejection of the economic value of the land it occupies.

Toronto City Hall expresses municipal political power in its spectacular design of two curving towers embracing the council chamber (the disc object) hovering above a podium where the Mayor and councillors can stand for ceremonies, and its large public square, here being used for a celebration of the South Asian community. The photo on the right shows the view from the podium on a day when the square is not in use for an event. Compare this use of space with that of the bank towers in the financial district, shown below, which aim to maximize the economic value of the real estate they occupy by covering most of it with rectangular buildings on rectangular lots that aim to maximise the economic use of expensive real estate . The political power of place is often demonstrated by a rejection of the economic value of the land it occupies.

Expressions of Economic Power in Place.

Unlike political power which mostly opts for distinctive architecture and open spaces, economic power is most obviously displayed through height. Thus financial districts are marked by clusters of skyscraper office buildings where wealth is concentrated and managed, and the only open spaces are ones that have been demanded by planners. In Toronto signature towers of four of the five major Canadian banks, all designed by internationally renowned architects, occupy the four corners of a single downtown intersection. Less obviously, economic power, can be displayed in sprawling campuses of corporate headquarters such as those of Apple, Microsoft and Google. But much of the economic power in late capitalist economies is discrete and distributed and has little obvious presence in places. Stock exchanges are mostly electronic hubs for trading and the signature bank towers in Toronto are now all owned by real estate investment companies, which, like pension funds, mostly eschew such popular and obvious symbols of wealth as signature skyscrapers.

Two versions of economic power of place. The concentration of bank towers in the financial district in Toronto 1995 expresses power by height and design – white tower is Bank of Montreal (Ed Stone, architect), slim tower to its right is Scotiabank, shorter and to its right is Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (Mario Pei), three black towers in front of those are the Toronto Dominion Bank (Mies van der Rohe). The photo on the right shows Building 1 on the Microsoft Campus in Redmond near Seattle, the first of over 100 low-rise buildings on a 260 acre site with its own shopping mall and sports fields. It is the sheer, mild-mannered scale of the campus that is impressive.

At a larger scale the growth and continued prosperity of world cities – New York, London, Tokyo, Hong Kong, Singapore and more than a hundred others – is a reflection of the fact that they have become the command centres of global trade and finance. Together they form a neo-liberal network of prosperous and powerful places that continue to attract wealth while other less powerful places languish on the periphery.

A sign in the City Hall of Mississauga, a suburban municipality on the west side of Toronto that is the sixth largest city in Canada, expresses its hope to participate in the global city network and to enhance its economic power of place while continuing to be “a place where people choose to be”.

A sign in the City Hall of Mississauga, a suburban municipality on the west side of Toronto that is the sixth largest city in Canada, expresses its hope to participate in the global city network and to enhance its economic power of place while continuing to be “a place where people choose to be”.

Success in the world city network and for other places in its margins, means growth. Since about 1990 this has come to be associated with place branding as a way to attract investment and grow the economic power of a place. This connection is sometimes made explicit, for instance on the website of Resonance, a company that uses strategy, storytelling and design “to build brands that grow places, products and people,” and which includes a short video “Place Branding: Chris Fair (a consultant) on the Power of Place.” A narrower example is Foursquare, a business that offers an app for mobile phones to unlock the power of place for marketers and developers by providing instant access to local businesses and amenities.

There is a very different, bottom-up notion of the economic power of place for communities outside the world city network. The Power to Change is a UK group that aims to put business in community hands by addressing the unique working needs of people in specific locations. Early in 2017 they offered an online discussion and blog of power of place in order to facilitate community collaboration for growing businesses. Their argument is that addressing social challenges and building cohesive communities necessarily happens in particular places, and that supporting local businesses in these places is an essential part of that process. This understanding of the economic power of place aligns well with Dolores Hayden’s community power of place because both involve the community working to make a place even as the place defines the community.

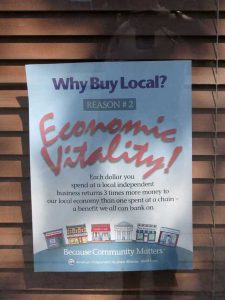

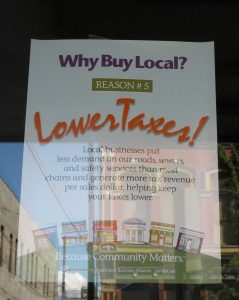

Community based economic power of place. Two of a series of signs in store windows in Ellensburg, Washington, in 2011 that advocated local initiatives to grow business.

References

• Agnew, John and Duncan, James (eds) 1989 The Power of Place: Bringing together geographical and sociological imaginations, Unwin Hyman, Boston

• Foursquare, Unlocking the Power of Place for marketers and developers, accessed 2017 https://medium.com/foursquare-direct/unlocking-the-power-of-place-for-marketers-and-developers-introducing-pilgrim-sdk-by-foursquare-ee879c502088

•Gehl, Jan1987 Life Between Buildings: Using Public Space, van Nostrand Reinhold

•Hayden, Dolores 1995 The Power of Place: Urban Landscapes as Public History MIT Press

•Lock, L.R. and H.J.Gibb 2003 “The Power of Place” Midwifery Vol 19(2) accessed 2017 at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12809633

•Neighbourhood Change Research Partnership 2016 Connecting the Power of People to the Power of Place: How Community Based Organizations Influence Neighbourhood Collective Agency, accessed 2017 http://neighbourhoodchange.ca/documents/2016/12/neighbourhood-collective-agency.pdf

•Power to Change, 2017 The Power of Place accessed 2017 http://www.powertochange.org.uk/blog/the-power-of-place/

•Project for Public Spaces, 2011 The Power of Place: A New Dimension for Sustainable Development accessed 2017 at https://www.pps.org/blog/the-power-of-place-a-new-dimension-for-sustainable-development/

•Rollason, David 2016 The Power of Place: Rulers and their palaces, landscapes, cities and holy places Princeton UP

• Saleebey, Dennis 2004 “The Power of Place: another look at the environment,” Families in Society, Vol 85 (1) Jan-Mar 2004

•Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, Power of Place, A Permanent Exhibition, accessed 2017 https://www.si.edu/Exhibitions/Power-of-Place-4843

•Steelcase 2014 Power of Place: The Office Renaissance accessed 2017 at https://www.steelcase.com/research/articles/topics/employee-engagement/power-of-place/

•White, Richard and John Findlay (eds) 1999 Power and Place in the North American West, University of Washington Press