This is a brief post stimulated by something I recently read online in The Atlantic that took me by surprise because it adds an entirely different aspect to the idea of what might be considered placeless. Charlie Warzell, who writes about trends in social media, began by putting things in a context which applies to anybody reading this post: “You are currently logged on to the largest version of the internet that has ever existed…one of the 5 billion-plus people contributing to an unfathomable array of networked information…” Then he declared:

“The sprawl has become disorienting. Some of my peers in the media have written about how the internet has started to feel ‘placeless'”.

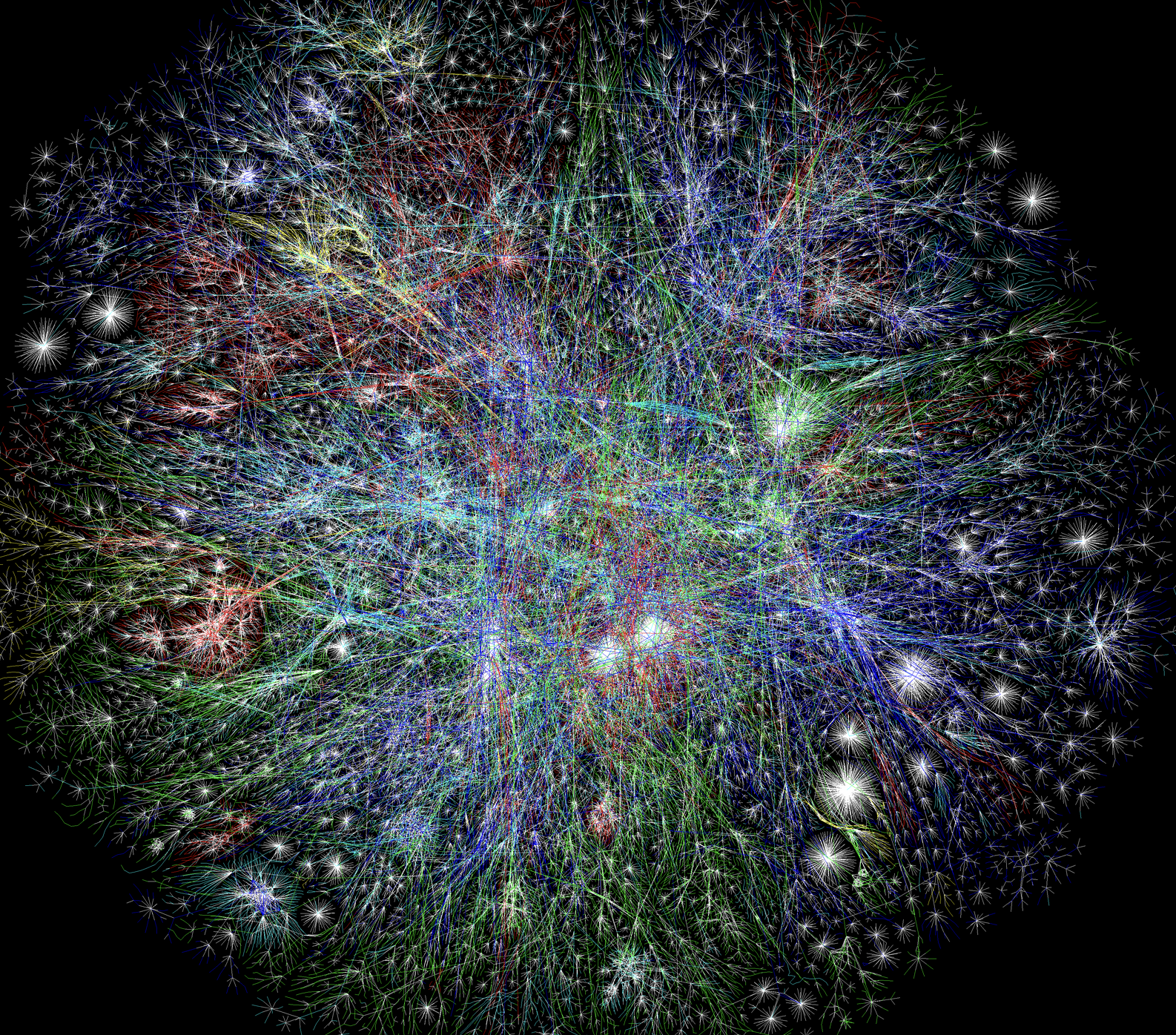

But isn’t the internet inherently placeless – a network of flows and websites that are simultaneously everywhere and nowhere.? Cables and radio waves that carry the flows are either buried or invisible; there’s no easy way to know where websites like this one are based, and the computers and devices with which they are accessed are mass produced. The large data centers that house the cloud are clusters of unremarkable, industrial buildings in obscure locations; the smaller data centers with “meet-me rooms” where intercity fiber connects with local providers are mostly anonymous. Of course, you can use your devices to search for local shops or for wayfinding, and software does prompt us to turn on location services, but these are little more than gestures to place in an overwhelmingly placeless system.

Networks and Nodes of the Placeless Internet [Source: Mountpeaks]

Bu I think that what Warzell means when he says “it “the internet has “started to feel placeless” has nothing to do with what I have always thought of as ‘placeless.’ What it suggests is that for him, as a devotee of online communication and social media, the internet once seemed to have distinct ‘places’ that gave it both coherence and diversity. He doesn’t say, but perhaps these were like communities of users, or perhaps it was just that the big apps – Facebook, You Tube, Twitter and so on – had identities that was embedded in how they conveyed information and how they were used. Anyway, his comment suggests that what he previously experienced as organized diversity of the internet is fragmenting into incoherence with no consistency, no discernible pattern. Online experiences, he suggests, are become increasingly “unique to every individual.”

Warzel references an article in NY Times Magazine by John Hermann, who also uses the word “placeless” to describe the fragmentation that he thinks is currently happening to media in the US: “As the election looms, the media — old but also new, niche but especially mainstream — is falling to pieces.” It will, he writes, “be a placeless race, in which voters and candidates can and will, despite or maybe because of a glut of fragmented content, ignore the news.”

A word cloud that gives a sense of the new meaning to the placeless internet [Source: Graph Design]

The only conclusion I can take from this is that the internet has contributed to the development of a metaphorical meaning of ‘placeless’ as a way to describe whatever in the world seems to have become so unstructured and incoherent that you can no longer see where you are or how to find a way through it (which at the moment seems to apply to many things). And in the particular case of the internet, place is, to borrow a phrase from Huw Halstead, significant only in its absence.

A Footnote on the Development of this new sense of “Placeless”

That comment of Halstead’s was in an edition of the journal Memory Studies devoted to the impact of digital media on memory, in which he describes how the rapid growth of the internet in the 1990s prompted contrasting opinions from ‘cyber-visionaries’ and ‘cyberpessimists’.

The optimistic visionaries then envisaged the digital world as creating a sort of progressive placelessness that permitted greater freedom, enhanced democratic participation, and promoted global solidarity because it was unencumbered by the restrictions and antagonisms of boundaries and rootedness. This was a digital version of modernist, international style architecture, which promoted (and still does) the idea that one style is good for any climate and any location.

Cyberpessimists, on the other hand, feared that digital technologies, such as those of the internet, would lead to a different form of placelessness in which citizens would be separated from real neighborhoods and communities where daily life takes place, and memories would be cut loose from the distinctive places in which they were formed and which gave them meaning.

What the recent comments about the emergence of “the placeless internet” suggest is that with the subsequent development of social media and mobile phones, the internet came to be experienced not so much as placeless but as creating new types of communities or digital places on Facebook, Twitter, You Tube, Tik Tok and so on, and there seemed to be a coherence to this. It now seems that these and other uses of the internet have fragmented into a constantly shifting kaleidoscope that involve unexceptional everyday use for messages and searches, influencers with short half-lives, sparks of viral activity, and echo chambers filled with almost indecipherable mixture of information and misinformation about the world. It’s an expanding universe moving in many directions at once.

The feeling that the world or some aspect of it has lost its familiar patterns and become become incomprehensible is nothing new. In 1611 John Donne wrote in his poem The Anatomy of the World : “Tis all in pieces, all coherence gone.” In 1919 William Butler Yeats wrote: “Things fall apart, the centre cannot hold.” What is new is that this feeling is now being characterized as ‘placeless’.

Perhaps that is a good thing. It implies that place, no matter how it is understood, is about coherence, order and comprehensible meaning. One obvious way of resolving placeless uncertainty, metaphorical or otherwise, is to attend to places.