A Note on Approach

It has taken me longer to post this discussion about the future of places that I anticipated. This is partly because the coronavirus intervened but mostly because what I had naively expected to involve quite straightforward projections of current trends I had identified in previous posts turned out to involve unlikely outcomes and complex interactions. I spent some time lost in a maze of speculations about technological, political and economic possibilities, and then decided to focus on just five overarching factors that I think offer a reasonable degree of certainty about what will happen to places this century, especially in the near future. These factors are: the place legacy of the present, peak population, urbanization, climate change, and, somewhat more speculatively, shifts in a shared view of the world.

Speculations about the future frequently tend either towards dystopian bleakness or utopian marvels. My approach falls somewhere between these. It is based mostly on projections of existing trends. However, in order to keep this post as concise as possible I have compressed or omitted material and data that supports or qualifies my arguments. These I detail in three other posts that serve as footnotes or appendices to this one: 1. Legacy and Population, 2. Urbanization, and 3. Climate Change and World Views.

Definitions and Assumptions

First, however, I want to re-emphasize that what I mean by places are those aspects of the world, especially built environments, which have their own names and which we know directly because we encounter them in the course of daily life and travelling. Places in this sense include our homes, neighbourhoods, cities and regions. In our daily encounters with them it is their distinctiveness that is usually regarded as significant. However, for all their apparent uniqueness, the identities of places are in some respects the product of broad social, technological and environmental processes that sweep around the world like epidemics affecting everywhere in broadly similar ways, yet with distinctively local manifestations. These processes were once slow, taking decades or centuries to spread across continents, but in the recent past they have become increasingly fast moving and far-reaching. Here I am interested in the broad, large-scale processes that are likely to affect place identities over the course of the 21st century.

My focus in previous posts on history and trends has been on Europe and North America. This corresponds reasonably well to the category of ‘more developed regions’ (Europe, North America, Australia, New Zealand, Japan), used by the United Nations in its population and urbanization projections, and which informs my discussion here. My discussion also broadens to a worldwide scale both because most future growth will be in ‘less developed regions’ (everywhere else), and because, as the Covid-19 pandemic has shown so clearly, global connectivity is now a fact of everyday life.

The pandemic has also shown that established practices and expectations can be disrupted by unexpected events. In the 21st century these include are two widely identified, potentially catastrophic disruptions to places: nuclear conflict and runaway artificial intelligence. I do not consider these, nor other unpredictable existential risks and possible technological misfortunes. I also do not consider possible tipping points when change, whether rapid or slow, become irreversible as it passes a threshold that leads to a different stable state. These could be environmental (particularly associated with climate change) or political (such as the decline of democracy and rise of autocracy, or revolutions), but are unpredictable and avoidable if appropriate measures are taken. My focus is on projections of current trends.

The Legacy of Present Places

The built environments of places are enormous investments of time, effort and money that tend to survive political and economic upheavals, at least those that are short-lived events, and last as long as they continue to have value. The consequence is that every generation inherits a legacy of places and leaves its own legacy to the future.

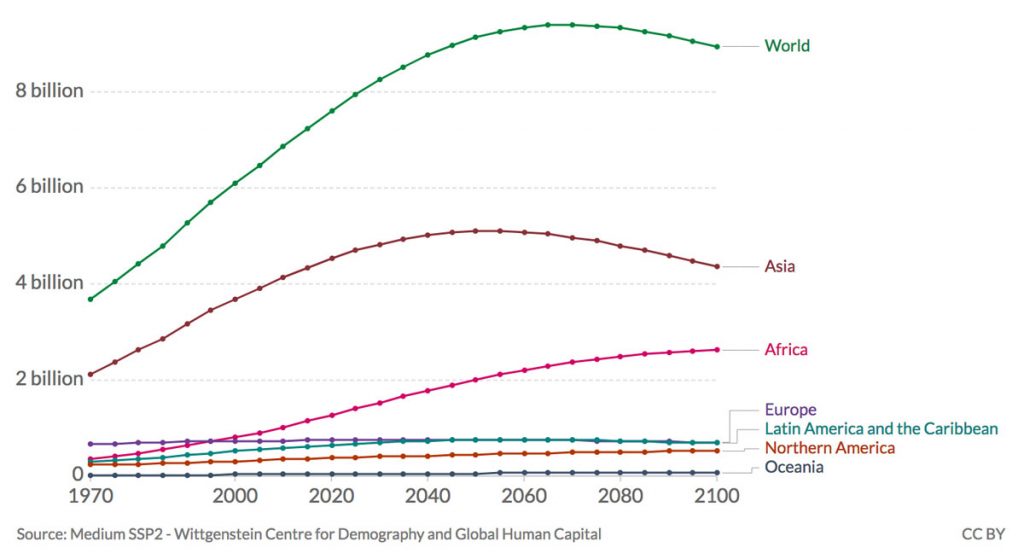

The place legacy of the present age, which I define as beginning about 1970, is the largest there will ever be. Never before have so many places been made to accommodate so many people, more than four billion, in such a short time. And a legacy of this scale will never be repeated because for the first time in the history of humanity the growth rate of global population is now in steep decline with no likelihood of reversal.

Since 1970 a frenzy of placemaking in the developed world has produced new towns, vast suburbs, downtown skylines transformed by skyscrapers, social housing projects, shopping malls, commercial strips, industrial parks, resort developments along coasts and in mountains, plus all the related infrastructures of expressway networks, airports, communication towers, container ports, high speed railways, and sewage treatment plants. The present age is also the first to bequeath to the future thousands of heritage sites and environmental areas deliberately protected from change for the foreseeable future.

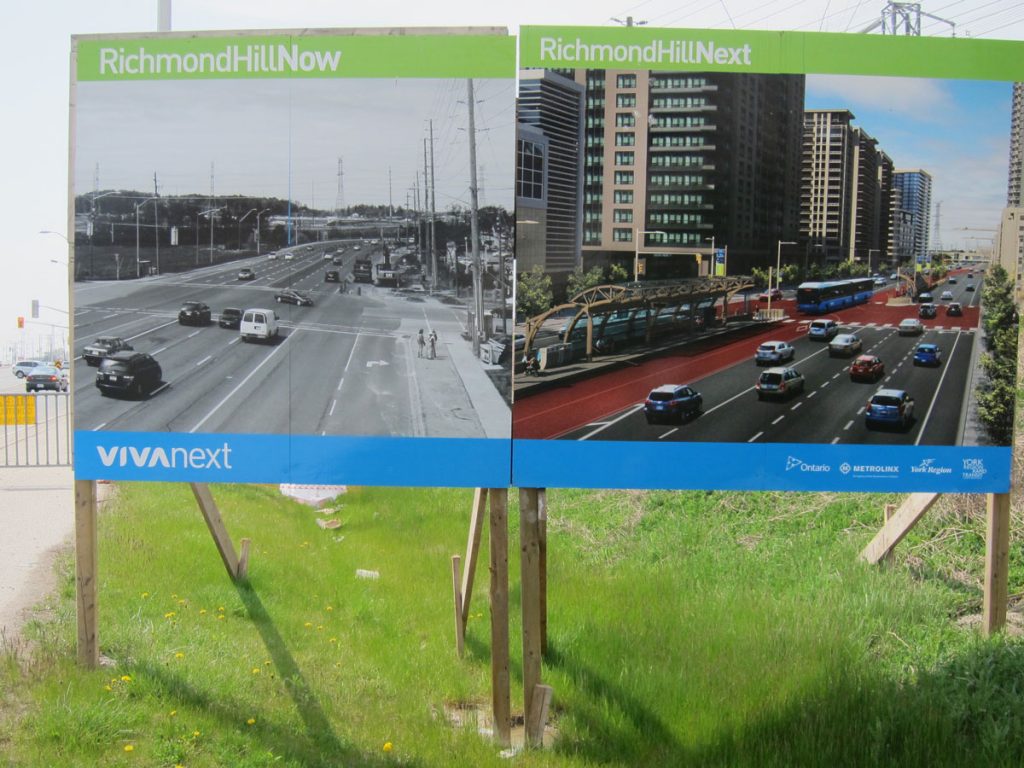

Downtown and suburban Toronto. As far as I can tell the oldest thing visible in either of these photos is one of the black skyscrapers (designed by Mies van der Rohe) to the right of the CN Tower that was completed in 1968.

This legacy is so new and so extensive it is unlikely to be modified in a major way any time soon, which means there are unlikely to be many surprises in the near future in how places will be made and experienced. In the longer run, of course, the place legacy will age, and incremental changes made in response to fashions, technological innovations and climate change will accumulate. But if the legacy of the 19th century to the present is any indication (railway lines and stations, institutional buildings, residential districts, entire towns), much of the legacy of the recent past is likely to be around for a very long time.

Peak Population and its Implications

The 21st century is demographically exceptional. Projections (by the UN here, by the Wittgenstein Centre here, and most recently in The Lancet in July 2020 based on careful analyses of fertility rates and the impacts of education and contraception) show global population growing by about another 2 to 3 billion, which is much less than the growth of the last 50 years, then peaking and beginning to decline (the Lancet article suggests global population will peak at 9.7 billion in 2064, the UN suggests a peak 10.9 billion about 2100). The huge implication of this demographic reversal after millennia of continual growth will be a shift from needing more places for more people to fewer people in shrinking places.

Global population projections mask considerable unevenness in both time and space. Almost all future growth will happen in Asia and Africa, and after 2050 mostly in sub-Saharan Africa. For those regions the short-term challenge will be one of making new places and expanding existing ones. But in most of the more developed countries population growth through natural increase (i.e. internal growth because the number of births exceeds deaths) has already peaked and begun to drop (the U.S is an exception; there this is not expected to happen until about 2030). This drop has been offset by immigration, particularly from less developed countries, and this has led to the recent cultural and racial diversification of populations and especially urban places.

In countries where immigration has been limited, for instance Japan, Russia, Poland, Italy and Spain, total populations are beginning to decline. The Lancet projections are that populations in Japan, Spain, Italy Thailand, Poland, Hungary and about 20 other countries will by 2100 drop to half of their present numbers. These are the forerunners of the demographic transition associated with aging populations that will increasingly affect everywhere, including less developed nations. This transition will lead to widespread adjustments to places, including fewer children and schools, more hospitals and long term care facilities, and all the attendant social problems of an ever smaller working population supporting more elderly people. More speculatively, after peak population there could be to a transition to fewer, smaller places that are environmentally and demographically sustainable.

Urban Places and Future Urbanization

Regardless of whether overall populations grow or decline, the places of the future will be increasingly urban and in large cities, continuing trends that have been accelerating for some time. There are five main aspects of this.

Urban Areas are Expanding Faster than Population: The UN Habitat Data Booklet indicates that between 1990 and 2015 urban land expansion rates were about double urban population growth rates. In other words, as populations were increasing densities were declining as metropolises spread outwards in relatively low density suburban, exurban and peri-urban settlements. This phenomenon is also apparent in the animations at the Atlas of Urban Expansion.

More People in More Urban Places: The UN, which has measured populations of ‘urban agglomerations’ since 1950, projects that at the global scale the proportion of people living in them will increase from about 55% now to almost 70% in 2050. Urban agglomerations include everything in some way urban – towns, cities, slums and shanties, suburbs, exurbs, satellite cities. This overall increase mask major differences between less and more developed regions.

New Cities and Slums in Less Developed Regions: Almost all future urban growth, about 95%, will be in less developed regions, mostly Africa and Asia, where about 2.1 billion additional people will be added to urban areas by 2050. To put this in perspective, it is equivalent to building 10 megacities the size of London or Jakarta every year for 30 years. In fact, several hundred much more modestly sized cities are already under construction or planned, more than 100 in India alone (e.g. see here and here). Most are satellites of existing urban areas. They give a sense of what future places in new cities might be like. The preferred model seems to be new cities in China (which has invested heavily in African new cities) – skyscraper offices and apartment towers, wide boulevards with ample space for vehicles, an emphasis on hi-tech industries, a mixture of moderately dense residential areas, both high-rise and low-rise, and attention to sustainability and low carbon emissions. Nothing very remarkable in terms of place identities: an article in The Guardian expressed it this way: “The bland look of nonplace is perceived by local elites to be sign of successful modernity.” According to one observer many the of new cities built thus far in Africa do not pay much attention to the socio-economic realities of local people and appear to be “planned without inhabitants in mind.” Jane Lumumba, a planner, cautions that: “What is worrying is that there is little recognition of place, economy, context and even poverty in these cities.”

Three new cities in less developed regions. Gurgaon, India; Konza Techno City, Kenya; Nova Cidade do Kimbala, Angola.

New cities will only meet a fraction of projected growth in less developed countries, much of which will be probably be accommodated in slums (places defined by the UN as lacking running water, sanitation, infrastructure, and sufficient dwelling space). There have been remarkable recent accomplishments in reducing poverty in many of these countries, but these have not been able to keep pace with population growth, and the scale of slums and informal settlements has actually expanded. In Nigeria 42 million people currently live in slums, in India about 100 million, numbers that can be expected to grow substantially. It is doubly unfortunate that many of these disadvantaged places and vulnerable populations are in regions of Africa and Asia where the consequences of climate change are expected to be especially harsh because of rising temperatures and more intense rainfalls.

Incremental Change in Slowly Growing Cities in More Developed Regions: The annual growth rate of urban populations in more developed regions has been declining for half a century. In the 1960s, when about 110 million people were added to cities and towns in Europe and North America, it was 2%. It is now about 0.5% and is expected to drop to 0.3% a year by 2040. In other words, overall urban growth in developed countries will slow to little more than a crawl by mid-century. This slowdown might seem to be belied by reality if you live in a city in Europe, Australia, or North America with a skyline crowded with cranes, and suburbs that always seem to push outwards. The explanation is that some larger cities and a few smaller ones seem to attract most of the limited growth, perhaps because of the quality of their environments or their role in the network of world cities. Other places will stagnate. Selective urban growth is expected to continue, and will happen even in countries where there will be overall population decline. It seems that bright lights are irresistible.

The character of future places is already established in plans and policies. This billboard projects change along a planned rapid transit route in a satellite city of Toronto. While change locally may be considerable, the character of the change to place is predictable.

Where growth does occur it seems unlikely that the character of urban places will alter quickly or significantly even though particular places may be substantially redeveloped. This is partly because of the enduring place legacy, partly because growth will be slow, and partly because current plans and policies will guide development along well-established lines for the next two or even three decades. Changes to built environments will be piecemeal and incremental, the result of individual projects. Their cumulative effects may in due course be considerable, but at the moment there is little evidence of radical architectural or planning approaches to suggest that they will hold any great surprises. In city centres there will probably be more densification with tall apartments and more bike lanes because these contribute to reductions of greenhouse gas emission. At urban fringes there will be more place branded, master-planned suburban developments, especially around satellite cities, where, unless something remarkable happens, personal motor vehicles of some sort will continue to be the preferred form of transport, continuing recent worldwide trends (including Europe).

The greatest changes will be social and demographic. Populations will age considerably, with fewer workers supporting more retirees, fewer child-care centres, more long-term facilities, and more elderly people complaining about the pace and character of change. Places will become more racially and culturally diverse, reinforcing the hybrid identities of urban neighbourhoods that have already developed in many world cities as immigrants from less developed parts of the world make up for shortfalls in natural increases. Increasing diversity has large political and social consequences. In the U.S. the Census Bureau projects that with current immigration policies by 2060 the “non-Hispanic White population“ will have shrunk by 19 million people while every other racial group will have increased.

Shrinking Cities: In regions and countries where immigration is not encouraged, such as Japan and Spain, or which are simply by-passed by growth, urban places will begin to shrink in population (though the largest cities such as Tokyo and Madrid are expected to maintain their magnetic properties and maintain or even increase their populations even as everywhere else declines). Without radical changes in immigration policies and attitudes regarding racial differences, shrinkage will accelerate towards the end of century as people age in place and peak population looms.

There really is no precedent for understanding the consequences of shrinkage on this scale and its political and economic consequences. But recent instances of shrinking cities in the rustbelts of America and Germany give some idea of what it might involve in detail (see here) – boarded up buildings, abandoned neighbourhoods and failing infrastructure. In a few cases, such as Youngstown in Ohio, a smaller future has been accepted and strategies for greening abandoned spaces have been created.

But I know of no discussions of what a 50 percent reduction in population on a widespread scale will mean for the places where people live and no likelihood of future growth. From the perspective of place this amounts to something like a slow progression into a post-apocalyptic future of abandoned buildings and neighbourhoods being gradually overwhelmed by decay and invasive vegetation. Should remaining inhabitants be clustered in compact settlements? How can that be accomplished? Or should some sort of very low density, dispersed pattern of places be permitted? But in this case, how can infrastructure of sewers, water supply and transit be maintained? What will happen to networks of expressways and 100-story skyscrapers that are no longer needed? Will places crumble like Rome in fifth century CE or be overtaken by vegetation like Mayan cities? Or perhaps some sort of new, sustainable approach with very different sorts of places will emerge.

The Place Consequence of Climate Change

Climate change permeates the future of places. It is a slow moving version of the Covid-19 pandemic. Both are global in range, ignore national boundaries, put the poor and vulnerable at greater risk than wealthy elites, involve exponentially increasing consequences that are easily dismissed before they become obvious by which time it is too late to do much to mitigate them effectively, demand forceful actions by governments, and have intense but erratic local effects.

Climate change has three distinct types of consequences for how places are likely to be experienced, managed and made in the future: changes in local and regional weather, mitigation measures, and adaptations.

First, it will affect regional and local weather patterns, most likely by making them more severe and erratic. These can take decades, perhaps centuries, to reveal themselves, though some are already apparent in record temperatures, floods and droughts. The 2018 Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, which considers what needs to be done to keep the increase in global mean temperature to no more than 1.5C, offers a bleak overview prognosis for 2100 if no actions are taken and business continues much as usual – decreased life expectancies, huge reductions in outdoor labour productivity because it will be too hot to work and almost everywhere a lower quality of life [Chapter Box 8 Table 2]. Subsequent research indicates that large parts of Africa and South Asia, and parts of the Middle East and even the coastal United States, may well become uninhabitable because of intolerable combinations of heat and humidity. Rising sea levels and associated storm surges and salt-water incursions could impact 300 million people by 2050, not only in China, Indonesia, the Nile and Mekong deltas, but also cities that include Miami, New York and San Francisco. These regional impacts will almost certainly lead to substantial population displacements, especially in South Asia and Africa where population growth is projected to continue for several more decades.

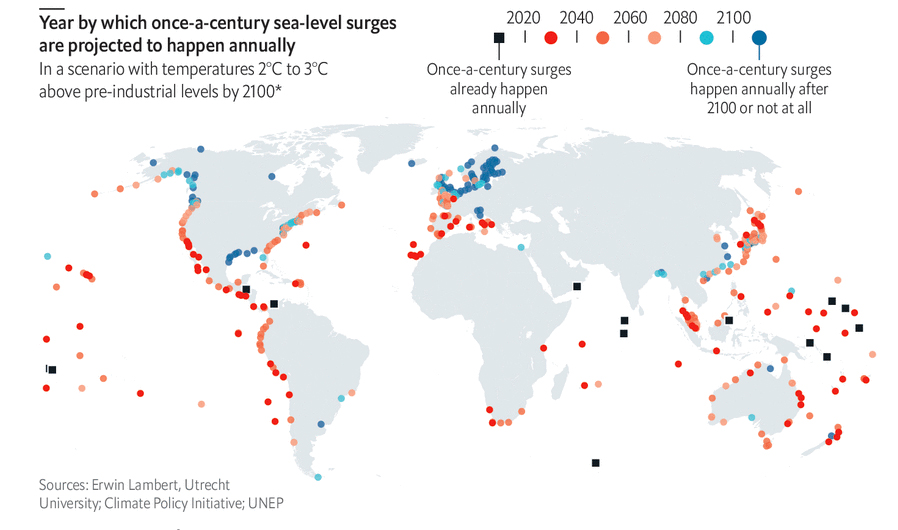

An example of widespread shifts in local conditions that are occurring and will intensify as a result of climate change. Source, The Economist.

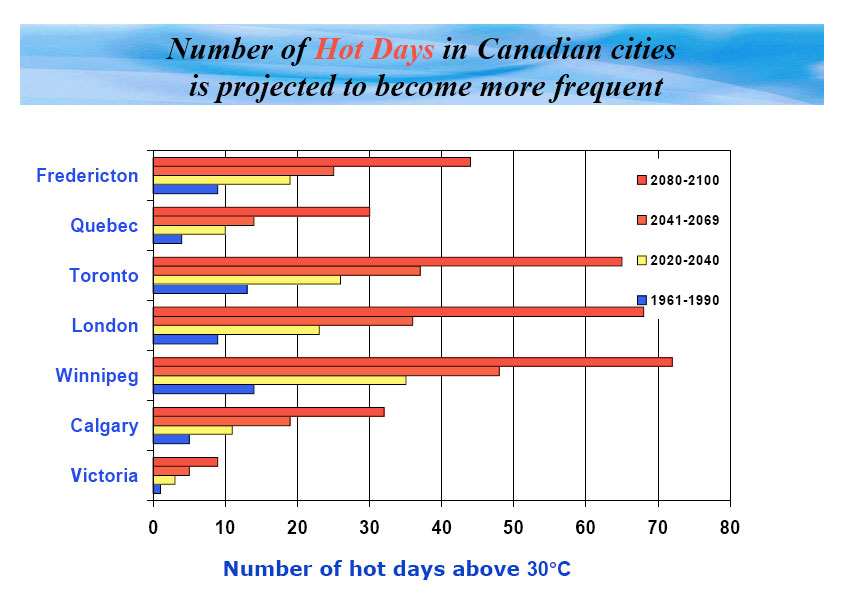

In short, if climate change is not kept within reasonable limits by stringent measures to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, it seems probable that many places around the world may, by the end of the century, have to be abandoned. And even where changes in weather are more moderate the character of everyday life could become very different. For instance, in the number of days when the temperature stays above 30C in Toronto is projected to increase from about 12 in the 1980s, to 40 in 2050 to 55 in 2100.

A Projection of the number of days above 30C in Canadian Cities (Winnipeg and Toronto could increase from two weeks 1961-1990, to more than two months 2080-2100); a student Friday Climate Strike in 2019. Source of Hot Days: Health Canada

Secondly, climate change can impact places through measures that are implemented in an attempt to reduce global warming. The main purpose of the IPCC 2018 Special Report is to argue that if “far reaching” mitigation measures to reduce carbon emissions are taken before 2030 this should limit future temperature increase to 1.5C and this bleak future can be avoided. Many places around the world are already applying mitigation measures, for instance, replacing coal and oil energy production with renewables, and increasing residential densities to reduce urban sprawl, and implementing programmes to retrofit old building to make them more energy efficient. Some of these have had an obvious impact on places, such as fields of solar panels. Some such as retrofitting buildings to be more energy efficient are largely invisible. Others such as densification are often combined with other planning strategies, such as finding ways to accommodate growth, so their impacts on built environments are difficult to distinguish.

In spite of these measures substantial gaps remain between what has been done, what governments have promised to do, and what appears to be necessary to prevent potentially severe and irreversible consequences of climate warming. The far-reaching mitigation measures needed to achieve the 1.5C goal require more extensive wind farms and solar fields, an end to deforestation, greatly reduced beef and dairy farming, and radical changes to the character of urban places including much greater densification, limited use of personal vehicles, doubling urban forests, and somehow redistributing employment and commercial activity into local centres in order to reduce commuting. These sorts of urban initiatives might be possible in the new cities of Asia and Africa, and indeed some are being adopted. They will be much more difficult to implement in existing cities, regardless of whether these are in less or more developed regions, because substantial places legacies have a rigidity that make anything more than incremental measures both difficult and expensive. However, shrinking populations and cities could provide some measure of mitigation.

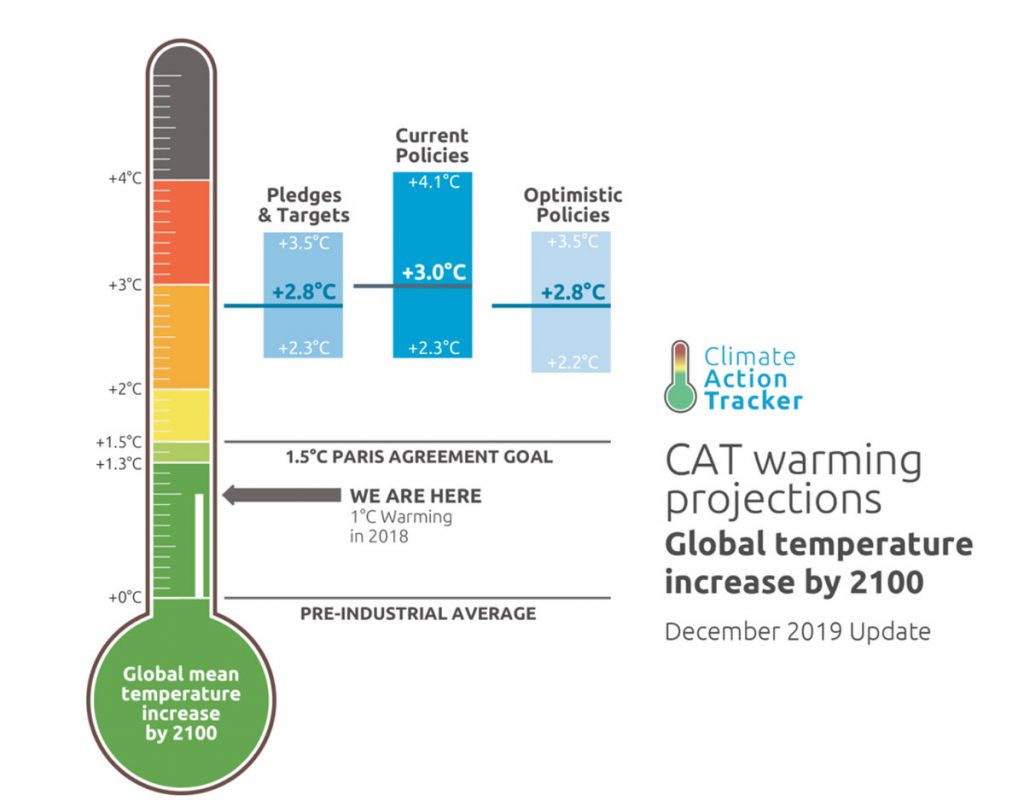

Furthermore, there are already indications that these sorts of measures, for all their benefits, could be insufficient. The IPCC Special Report was based on the assumption that the build up of greenhouse gases over the last two centuries will lead to a temperature increase, thus far about 1.0C, somewhere between 1.5C and 4.5C. Subsequent research re-examining this assumption has concluded that the range of warming will be narrower than this, but that the best case is a minimum increase of 2.6C, an increase that suggests a bleak future of challenging weather conditions for many places in the world.

Thirdly, regardless of the effectiveness of mitigation measures, place-based adaptations to more severe and erratic weather events resulting from climate warming will be necesssary. The IPCC Special Report refers to them as “transformational adaptations” and though they are not elaborated in detail they will have to be adapted to the environmental circumstances of particular places, for instance, sea walls to combat rising sea levels in coastal cities, and innovative building technologies to deal with melting permafrost in the Arctic. It is apparent from current practices that some, such as larger storm water drains to deal with intense rainfall events, or the warning systems and evacuation plans for floods and storm surges caused by typhoons in Bangladesh, will have few obvious impacts on the physical characteristics of places. However, others could involve major construction projects, for example barriers to prevent damage from storm surges, or installations for carbon capture. The most significant adaptations will involve the relocation of entire places from areas rendered uninhabitable because of extreme temperatures or because they are prone to sea level rise and flooding The latter include a number of world cities or at least large sections of them. As many as 13 million people in America might have to move elsewhere; more than 100 million in Africa (see here). Where they might relocate is not clear. Perhaps they could move to shrinking cities, but the increasingly exclusionary politics of many countries suggest that this is an unlikely outcome.

The Covid-19 pandemic has shifted attention away from climate change, and even though several countries have indicated that it remains a priority the likelihood is that it has been pushed down political agendas at the very time that mitigation measures are urgently required. A probable outcome is that measures already being implemented will continue to be made – shifting to renewable sources of energy, increasing densities, adding bike lanes, retrofitting old buildings, building sea walls, and so on. However, if the assessments in the IPCC Special Report are correct, these will be insufficient to keep global warming under 3C by 2100. Long before then the challenges of population growth and urbanization in Africa and Asia will have been exacerbated by extreme weather, and more intense droughts and heat waves around the Mediterranean will have accelerated shrinkage and abandonment of places. Climate induced mass migrations seem inevitable. The brief and blunt forecast is that over the course of the 21st century extreme and unpredictable weather caused by climate warming will make everyday life increasingly stressful in places almost everywhere .

Indications of A Changing Worldview.

Any chance of finding ways to mitigate the severe outcomes of the combined effects of climate change, aging populations, uneven growth and shrinking places (as well as plastic accumulation, overfishing, species extinctions, etc) must depend on a widespread change in attitude away from the current business-as-usual, rationalistic, economic growth model. In the past changes in places and ways of placemaking have often been preceded by a shift in how the world is viewed, and from this perspective there is, I think, evidence that a different set of attitudes is emerging that could have implications for the future of places.

First, rationalist interpretations of reality and truth, which have prevailed for several centuries, and lie at the base of many modern institutions and practices, have been challenged both by philosophers of science, and by movements for gender equality and racial equality such as Black Lives Matter. The supposed objectivity of rationalism is no longer universally accepted and has come to be understood as a product, at least in part, of white, patriarchal, European and North American elites. It may have practical value but also reflects significant biases. The implication is that there are cracks in the foundations of business-as-usual, conventional assumptions about the world works and should work. Ai Weiwei has expressed this eloquently: “Abandonment of rational thinking leads to a collapse in which fear and joy, ignorance and wisdom, all blow in the wind.”

Secondly, there is a long-term trend to environmental responsibility that has come to challenge age-old convictions that nature needs to be dominated and exploited. This shift began in the late 19th century both with the emergence of the idea of ecology and with the creation of national parks to protect wilderness. More recently it has been reinforced by the environmental movement that began in the 1970s, and involves the protection of threatened species and natural areas, ecosystem planning, the widespread acceptance of the importance of sustainable practices, and awareness of the human causes of climate change. While it is far from being a truth universally acknowledged that natural processes should be worked with rather than against, the historical evidence of a trend towards environmental responsibility is clear, though it may be too fast for those with vested interests in environmental exploitation and too slow for those with an environmental conscience. Nevertheless it seems very likely that this trend will be accelerated by the need to cope with climate warming, declining populations and expanding cities.

Thirdly, the incredibly rapid adoption of electronic communications and international travel has shrunk the world and made universal, rapid global connectivity a fact of everyday life. Electronically there are no isolated places, everywhere is connected. These are insights consistent with ecology that are reinforced by the fact that our food and most other things depend on worldwide supply chains, racial diversity in cities, and the way a viral mutation in a bat in a remote cave in Asia has consequences that swirl around the globe.

Connectivity has reorganized how people relate to places because it demonstrates that what happens here, in this particular place, can contribute to broad effects that rebound onto other places and back to this place. Connectivity has practical significance. The IPCC Special Report on climate warming notes that: “local knowledge, the understanding and skills developed by individuals and communities specific to the places where they live, is necessary to inform decisions about adaptations to climate warming.”

What this suggest to me is that a new basis for ways of making and relating to places could be emerging, one that is informed by environmental contexts and ecological implications, is socially inclusive, understands that there really are limits to growth, and acknowledges that places are simultaneously both open to the world and openings to the world. Its diffusion will continue to be challenged by interests vested in fossil fuels and by illusions of perpetual economic growth. There will continue to be electronically connected non-place communities promoting discrimination and exclusion. There will continue to be inequalities between places that grow and the others that stagnate or shrink. But the realities of the consequences of climate change and slowing growth will become increasingly difficult to ignore because they will play out in the places of everyday life. As this happens connectivity will ensure that local experiences and knowledge about new ways of managing places should come to be widely shared.

This developing worldview might in the long term affect how future places will look and function, but that is mostly a matter of speculation. In the meantime it can offer valuable insights about finding ways to deal with the challenges presented by peak population, aging and more diverse communities, shrinking cities and the exigencies of climate warming, ways that think from places outward.

Postscript to the Future of Places

My assumption behind this post and those on the history and future of places, has been that place is not some sort of incidental amenity. Its value spans generations and cultures, and is manifest in attachment, belonging and dwelling somewhere, in putting down roots, in being part of community that shares responsibilities, in a commitment to home and efforts to rebuild it after disasters. Although this value is not universally shared (some pay little attention to place because their interests are focused on economic gain or other matters), evidence from archaeological sites and historical records shows that places always have been important aspects of how people everywhere have experienced and modified the world.

One conclusion to take from this is that people will find a way to make places that are relatively distinctive and meaningful no matter how bleak or difficult circumstances might be. Some aspects of those places are personal – gardens, decorations, memories. But their larger forms and appearances in villages, towns, neighbourhoods and cities are determined by prevailing social and cultural beliefs, circumstances and practices. While these constantly change in small ways, from time to time they undergo substantial changes as populations have grown, civilizations have expanded or shrunk, technological innovations have happened, and new ideas about what is valuable and beautiful have emerged. The consequence is that each historical era has left a place legacy that is a record of more or less distinctive practices of placemaking, albeit biased towards wealth and power because those attributes are vested in enduring structures.

Given this historical record, it is to be expected that the future of places will consist in part of a legacy of existing places, and in part of innovative placemaking responses to changing social and environmental circumstances that, according to current projections, will include the considerable challenges of population decline, increasing urbanization, and the diverse impacts of climate warming. All of these are global in scope but local in both cause and impact.

It is, however, not clear how these challenges will be met over the course of this century and therefore what changes will happen to places. This lack of clarity is in part because of the absence of any widely shared vision of the longer-term future as attention is focused on short-term concerns, such as elections and the Covid-19 pandemic. In a addition there are concerns about the possible decline of democracy, geopolitical realignments, faltering globalization, the disruptive effects of social media and electronic communication, growing inequality and concentration of wealth, and genetic engineering and artificial intelligence. All of these could have impacts on life in places and the ways places are made, but there is really no way of anticipating these or how or when or if they might happen.

This complexity and uncertainty combined with a lack of a general long-term vision restricts what can be said about the future of places to the relatively predictable but limited ground of forecasts about population, urbanization and climate. My hope is that a latent, emerging worldview which conflates environmentalism and localism is emerging, and that this will in due course inform how places are made. But this not equivalent, for instance, to the rise of rationalism with its renaissance aesthetic and notions of progress in the seventeenth century, and provides few hints about how urban neighbourhoods and places in 2050 or 2100 might differ in appearance and character and the patterns of everyday life from those of 2020.

What can be said with some degree of confidence is that places in the future will be mostly in very large cities. In more developed regions their character looks as though it is going to be more of what exists now until about 2050, and then will be marked by forms of abandonment as populations slide into decline. In less developed areas some places will be in characterless new cities, but many will be slums of some sort. Unless very substantial actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions are taken in the next few years, which seems increasingly unlikely, almost all places everywhere will experience hotter and more extreme weather or problems associated with rising sea levels. In some cases this will be so extreme that large parts of the population will be forced to migrate to elsewhere in more moderate climates, where they are unlikely to be very welcome.

To put it succinctly, projections of population, urbanization and climate change, which are probably the most dependable projections available, suggest that the future of places in the twenty-first century, will for many people, be extensions of what exists now, but increasingly filled with unprecedented difficulties for which past and present practices will offer few solutions.