This second post updating my earlier speculations about the future of places in the 21st century summarizes the five Shared Socioeconomic Pathways [SSPs] that inform the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2021), and considers the possible implications of these for places. The SSPs, or “narratives”, can be understood as sets of well-informed assumptions about ways societies might unfold up to 2100, and are supported by projections of population, education, urbanization and economic activity that are consistent with the assumptions of each narrative. In effect, they are forecasts of different social contexts that could impact the future character of places.

The SSPs have been developed since 2010 (see Moss et al 2010) to complement physical climate change models, notably the Representative Concentration Pathways or RCPs that have been used by the IPCC since 1990. In the Sixth Assessment Report the concentration pathways and socioeconomic pathways are integrated as a way to recognize that any assessment of the severity of climate impacts depends in part on the social, economic and political willingness to take measures to mitigate carbon emissions and to implement adaptations.

The five different pathways are an attempt to span a range of uncertainties about future relationship between political choices, greenhouse gas emissions, and temperature changes. Because their end date is 2100 it’s important to note that all projections become increasingly uncertain the further they are from the present.

The Five Shared Socioeconomic Pathways

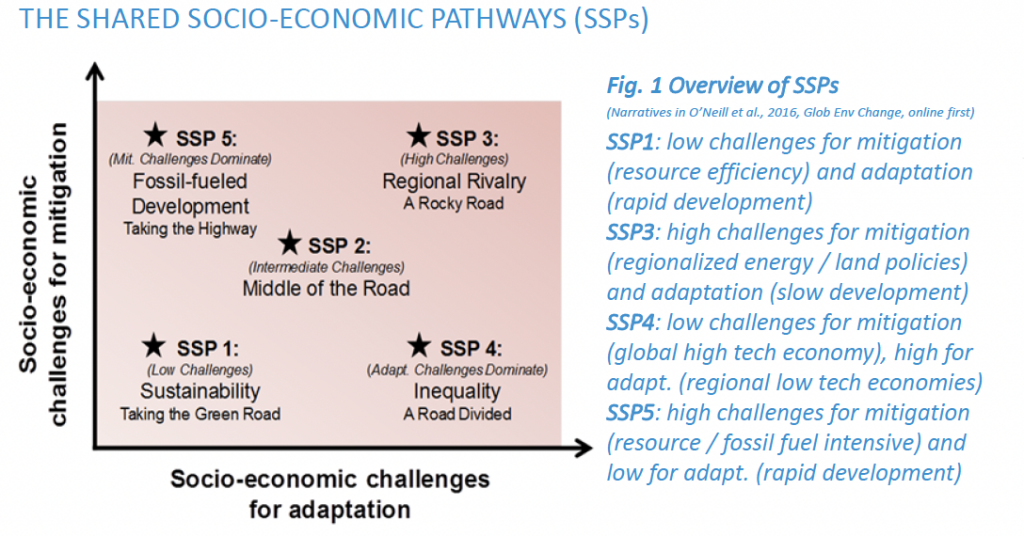

The diagram below, which is an elaboration of the original in O’Neill et al in Global Environmental Change, 2017, provides a useful visual summary of the five SSPs. I have abbreviated and paraphrased the descriptions given by O’Neill in order to emphasize aspects that have relevance for places. I have also drawn on Jiang and O’Neil, Global Environmental Change 2017 which offers projections of global urbanization to 2100 and Riahi et al, Global Environmental Change 2017, which offers projections of GDP including GINI measures of inequality.

SSP1 assumes a move towards sustainability and improved management of the global commons, with economic growth shifting toward an emphasis on human well-being and compact urban forms.This pathway is the best one for dealing with climate warming, presenting low challenges for both mitigation and adaptation.

SSP 2, which has been described as Dynamics as Usual, or Current Trends Continue, or Muddling Through, assumes social, economic, and technological trends do not change markedly from recent patterns of uneven growth, imperfectly functioning markets, with modest progress in sustainability. This is perhaps the most likely of the SSPs – a middle of the road in which governments dawdle, doing something about climate change, but putting off difficult decisions for as long as possible.

SSP3 assumes a resurgence of nationalism and geopolitical rivalries, with countries increasingly focusing on achieving their own energy and food security, and limited cooperation on global concerns. Slow economic growth and poor urban planning are expected to make cities unattractive.

SSP4 foresees a future of increasing disparities in political and economic opportunity that lead to increasing inequalities both between and within countries. The gap widens between an internationally-connected society that contributes to knowledge sectors of the global economy, and lower-income, poorly educated societies that are labor intensive. Environmental quality is a concern mostly for the affluent and where they live. Social conflict becomes common.

SSP5 assumes that continuing exploitation of fossil fuels will support rapid growth of the global economy and energy intensive lifestyles. This allows substantial investments in health, education, and institutions and encourages innovations, including geo-engineering for adaptation to global warming. Of course, it will greatly exacerbate the processes of climate change.

Projections Related to the Five SSPs

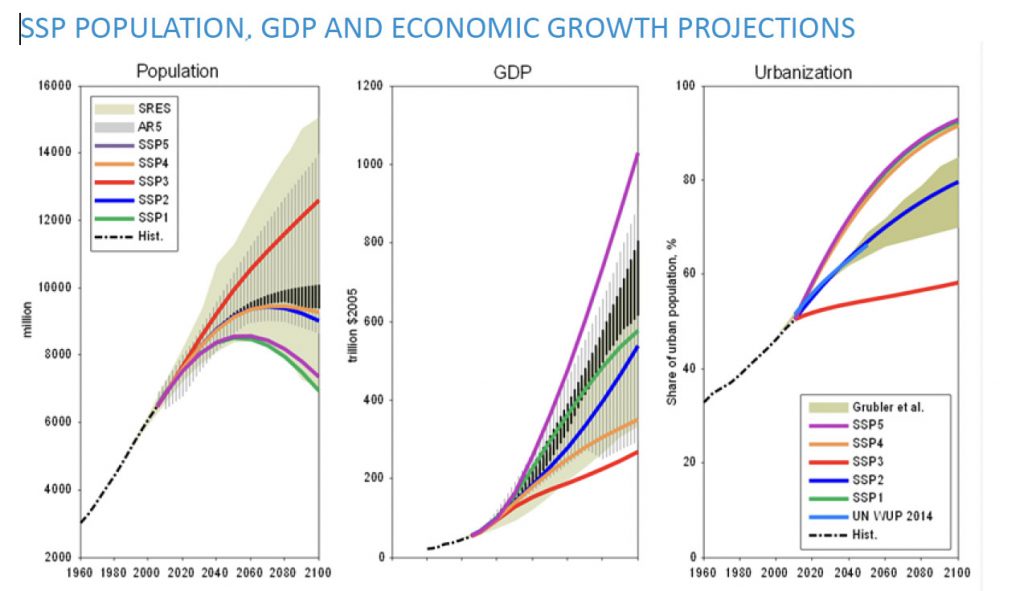

The five SSPs have been elaborated quantitatively by teams of scientists from IIASA (International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis), NASA and other research institutions. These elaborations include data bases and projections of population, education levels, GDP and urbanization, both globally and for individual nations, and they refine previous projections by the UN and other institutions, in some cases extending them from 2050 to 2100. The diagram below, for example, projects that with the fossil fueled growth of SSP5 there will be a global population decline before 2100, but substantial growth in GDP and urbanization. However under the regional rivalries of SSP3 there will be continuing population growth in the 22nd century, but slow economic growth and urbanization. The middle of the road, business much as usual future of SSP2 falls in between those extremes.

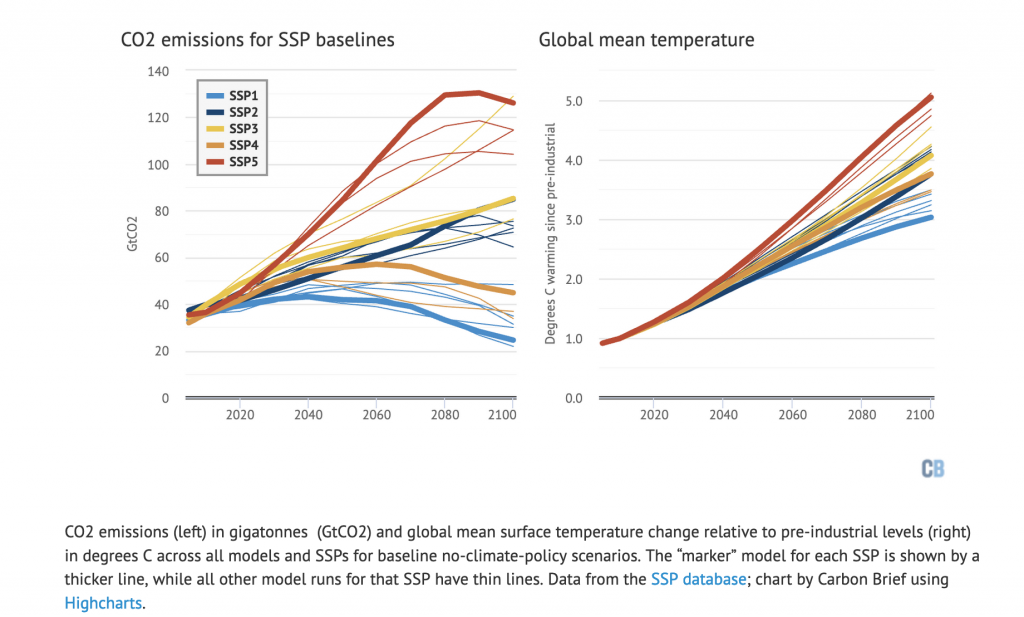

These projections do not take into consideration the environmental and climatic impacts that would be associated with the various scenarios. This has been done by Zeke Hausfather, who was involved in the research on SSPs and carbon emissions that informs the Sixth Assessment of the IPCC. His analysis, reported on his website Carbonbrief from which the following graphs are taken, shows that in all SSPs, even Sustainability, fossil fuel use will continue to play a role. And because of time lags in the effect of carbon emissions, under all scenarios global mean temperature is projected to rise by 2100 well beyond the target of the Paris Accord of 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. Even with in the Sustainability Pathway (SSP1) the increase could reach 3.1C, and with continued development based on fossil fuels (SSP5) it could be as high as 5.1C .

It is worth noting that independent projections by Climate Tracker suggest that with the continuation of current policies (roughly the Middle of the Road SSP) the global mean temperature could increase by somewhere between 2.1C and 3.9C by the end of the century, and even if all the current pledges and targets for mitigation are achieved the temperature increase is likely to be between 1.9C and 3.0C.

[Addendum: I recently came upon a 2018 paper by Kai Kuhnhenn, “Economic Growth in mitigation scenarios: A blind spot in climate science,” which points out that all five SSPs assume continuing economic growth. He advocates the consideration of scenarios that acknowledge the possibilities of no growth or “degrowth.” Given both the decline in greenhouse gas emissions that reflected a drop in economic production during the first year of the covid-19 pandemic, and the association since about 1800 between population growth, economic growth and carbon emissions, this does seem like a serious omission.]

Possible Direct Impacts on Places

Regardless of which SSP (or combination of SSPs, or some entirely different pathway) happens, the indications are that the impacts of climate warming will, in the absence of transformative modifications to current climate policy, progressively effect everyday life in places almost everywhere. Conversely, if transformative modifications are made, those too will impact life in places as they adjust to a low or zero carbon way of life. In either case, the effects will become more intense and widespread as global temperatures continue to increase over the course of this century.

Nevertheless, as I noted in a previous post, much of the legacy of present places – by which I mean all the roads, parks, buildings, towns and cities, industrial estates, names – will very likely endure in some form for many decades regardless of climate warming, and measure to mitigate or adapt to it.

However, this is not the case for places that are directly in the path of extreme weather. This was made apparent by the events of the summer of 2021, when there were heatwaves and extensive wildfires in California, British Columbia, Greece and Turkey that destroyed communities, and hurricanes and unprecedented rainfall that caused extensive flooding and disastrous damage to places in America, Belgium, Germany, and China.

For all the local damage and displacement of populations that these sorts of extreme weather events cause, they are a remote concern for the great majority of people. And given the general character and global scale of the SSPs and climate models it is difficult to grasp how they might impact particular places. In large cities, a few more extremely hot days every summer, more rain in winter, sea levels that rise a few centimetres a decade, can go largely unnoticed. So for the next two or three decades, regardless of which SSP comes closest to real life, the combination of the legacy of existing buildings and streets, slow and intermittent changes to the weather, and mostly unseen though critical mitigation strategies such as conversion to electrical generation from coal to renewables, means that most places and everyday life in them will stay much as they are now. Inconveniences caused by changes in weather and climate will seem incremental.

As the century progresses this will cease to be the case. Temperatures will rise, extremely hot days will stretch into weeks and months, intense rainfalls will overwhelm drains and flood walls, extreme weather will become more erratic. Consider that the extreme events of the summer of 2021 were a consequence of a global mean temperature increase of just 1.2C over pre-industrial levels. The SSPs and various analyses of current policies indicate a possible increase in global mean temperature of between 3.0C and 5.0C by the end of the century. A reasonable assumption is that extreme weather events will become far more intense, widespread and impossible to predict, and will have devastating impacts on everyday life in places. Nowhere will be immune from them.

Indirect Impacts

Economic projections associated with the SSPs project a growth rate of between 1% and 2.8% a year in global GDP to the end of the century. However, the growing costs of damages associated with extreme weather, and the expenses incurred by governments for emergency assistance that will not be paid off for the last event before the next one happens, raise doubts about this optimism. The costs of climate change will eat into government resources available for dealing with other social and economic priorities, such as housing, public health, heritage preservation and the arts. The gap between what people expect of federal or regional governments, and what those governments can provide is likely to grow, and responsibility for what happens in specific places will shift to more local levels.

Global Trends 2040, SSPs 2100 and the future of places.

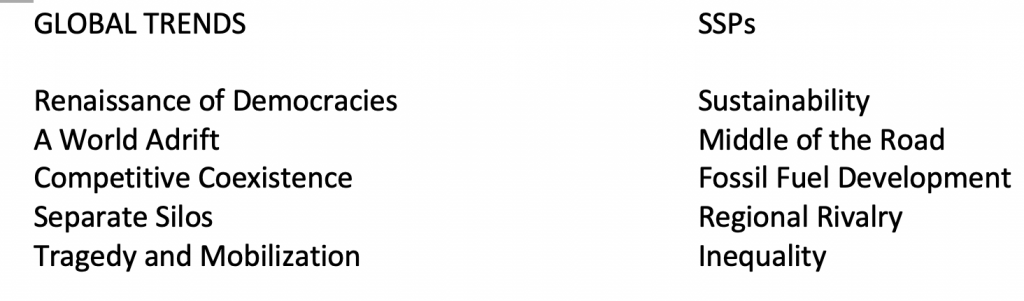

A combined total of ten different scenarios of the future are suggested by Global Trends 2040 (summarized in a previous post) and the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report. Of those ten narratives only two suggest a possible improvement in the quality of everyday life in places.

A Renaissance of Democracies associated with a revival of civic mindedness, especially if combined with technological breakthroughs to combat climate change, could involve a resurgence of pride of place that is also attentive to the necessity of global responsibility. In such circumstances, even as cities grow, populations age and economic growth slows, the physical forms and services of many existing places could be improved to reduce inequities, provide more security and maintain continuity with the legacy of the past.

In contrast, a Sustainable future necessarily requires transformations to current ways of living in order to give priority to conservation over production and consumption. There will be changes to food production and generation of electricity, which are the largest sources of carbon emission, but those that most obviously effect the places where the majority of people will live include larger cities with denser, walkable and bikeable neighbourhoods, more public transit, wide tree-lined sidewalks, green roofs, and a way of life that is more attentive to local and regional circumstances.

The message of all the other narratives is not encouraging. Socially, environmentally, politically and economically the prevailing sense they convey is that life almost everywhere will become more difficult as challenges expand, and opportunities shrink. Even proposals for positive change will be increasingly contested and difficult to implement. The uneven impacts of climate change will reinforce political divisions as those in climatically disagreeable places attempt to migrate to places where the weather is relatively benign and they will probably not be very welcome. Silos will emerge and inequalities intensify.

It is difficult to avoid the conclusion that as climates warm over the course of the 21st century daily life in places almost everywhere is going to become progressively more challenging.