In 1990 Jacques Attali, an adviser to the President of France, speculated that the twenty-first century would see an increasingly restless world of “rich nomads” and “poor nomads.” Rich nomads are people from privileged regions who roam the planet seeking ways to spend their free time by looking for places that offer pleasurable experiences. Poor nomads are uprooted people, mostly in the destitute periphery of the world, who hope to escape hopelessness, violent conflict, or starvation, by making their way to places that can provide sustenance and security. The consequence, he suggested (p.99), would be that: “The sense of place that gave birth to all previous cultures will become little more than a vague regret.”

We are now a quarter of the way through the 21st century. How does Attali’s prediction stand up to what has happened in the last thirty years? What are the impacts on place and sense of place? As I explored these questions I realised that we are now living in a world where displacement, or being in some way an outsider, is becoming a prevailing condition.

The Rapid Growth of Rich and Poor Nomadism

Attali’s prediction of growth in nomadism has so far proved correct. Since 1990 there has been rapid growth both in international tourism from rich countries, and in refugees and displaced people in poor countries.

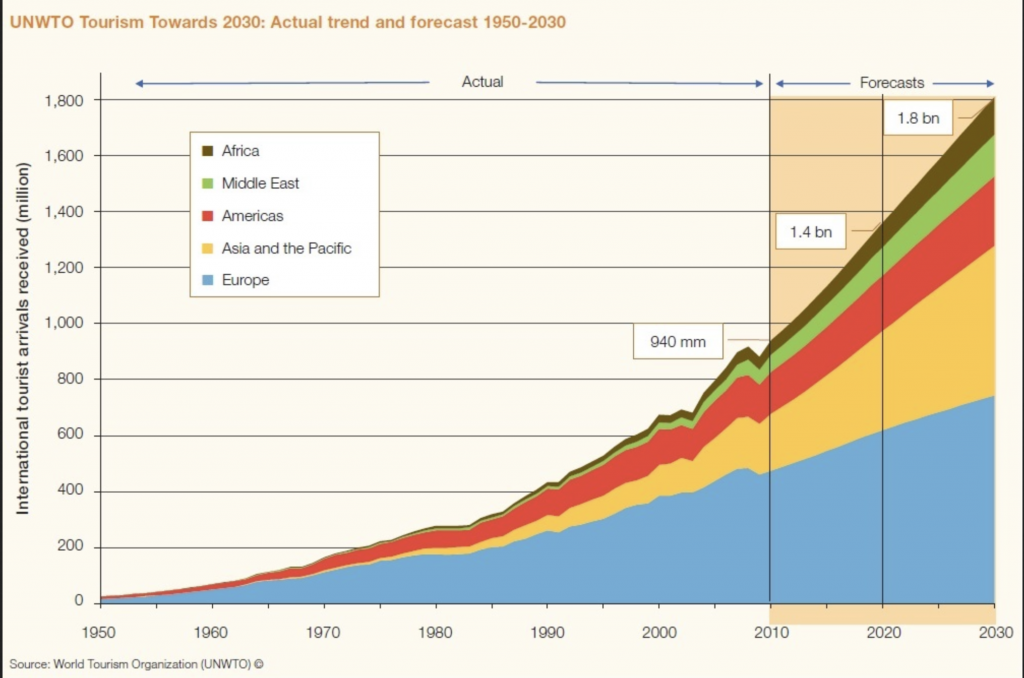

International tourism has surged in the last 70 years. The UN World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) has collected data about international tourist arrivals – people who travel to another country and stay overnight – since 1950. The graph below shows that there were about 25 million international tourist arrivals in 1950; by 1990 these had grown to 450 million. Since then the number has tripled to almost 1.4 billion, and is currently projected to grow to 1.8 billion by 2030. [A note of caution: these numbers are deceptive because it’s thought that perhaps only 5 percent of the world’s population (about 400 million) is rich enough to travel internationally, and many of those people travel several times a year.]

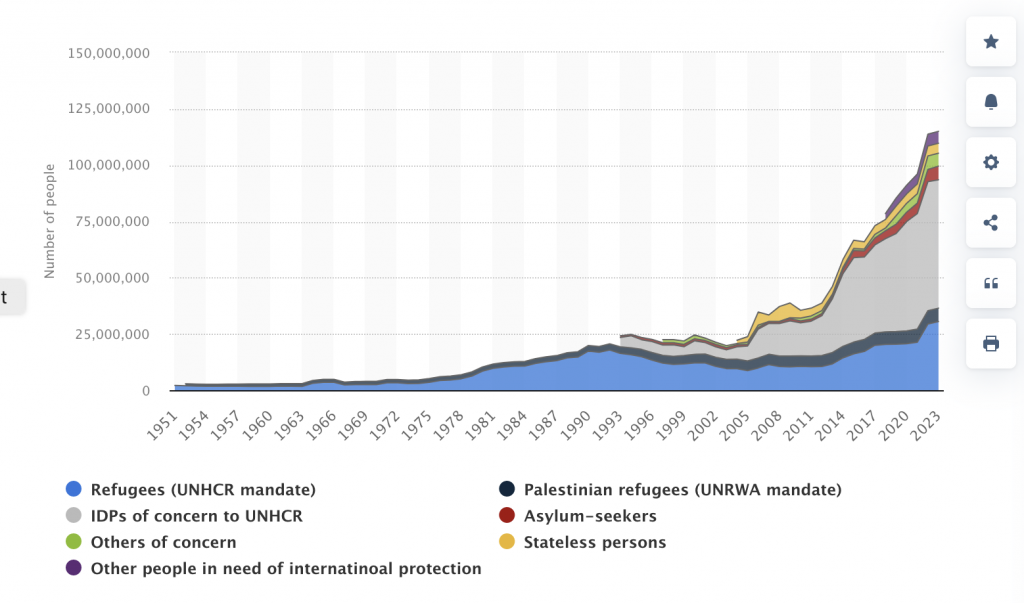

The UN Refugee Agency, UNHCR, has also tracked numbers of refugees since 1950, when there were about 2.1 million. This number grew slowly to about 20 million by1990. In 1993 UNHCR added asylum seekers and internally displaced people (those uprooted within their own country) for a total of 24.2 million poor people uprooted and on the move. Since then this combined total has more than quadrupled to about 120 million.

On the left numbers of international tourist arrivals 1950-2030. This graph was prepared by UNWTO in 2010, and does not show the impact of the Covid pandemic in 2019 and 2020, when numbers dropped to 1990 levels, but in other respects it corresponds to actual numbers. Source: UNWTO. On the right, Annual number of refugees, internally displaced persons and other poor nomads, 1951-2023. The numbers of poor nomads did not decline during the pandemic. Source: Statista.com

Place Impacts and Experiences of Rich Nomadism – Overtourism

Rich nomadism takes various forms. Cruising in the superyachts of billionaires or in huge ships; package holidays lasting from a few days to months to both popular and exotic destinations to lie on beaches, climb mountains, do yoga; business trips; students studying abroad; expats who have retired to a foreign country; individuals who collect countries or travel mostly to take selfies.

A consequence for sense of place of the recent growth in rich nomadism is that tourist places have become increasingly defined by economics. On the one hand, destinations that offer low cost vacations are popular, especially when promoted in online reviews and by agencies offering package trips. On the other hand, the income and employment provided by tourism have allowed otherwise depressed places to prosper, and they have become essential to the local economy even in cities that are major tourist destinations. The consequence is that their landscapes have been reworked with economically efficient, placeless, international style resorts, hotels, restaurants, and airports.

Since about 2010 the promotion of iconic destinations, especially through social media, combined with cut-rate air fares and packages, has led to ‘overtourism’. This has been simply defined in the National Geographic as “too many people in one place at any given time.” In effect, it is when the number of tourists is so great it simultaneously undermines the character of the places that attracted them and diminishes the quality of life for local residents. There have been vigorous protests against overtourism in Barcelona, Amsterdam, Venice, Dubrovnik, the Canary Islands, the Balearic Islands, Bali, and Mount Fuji in Japan. One small, symptomatic example of overtourism is Juneau in Alaska, a city of 32,000 where cruise ships can deposit as many as 18,000 visitors on a single day, and residents are trying to restrict cruise ships on Saturdays so that they can have the city to themselves for one day a week.

Overtourism raises the significant issue for place of whether some types of attachment to, or association with, a place are more important than others, and whose voice should carry the most weight about its identity. Should it be the year-round residents who have roots there? Should it be those who depend on income from tourism? Or should it be the international tourists for whom a place’s attractions are regarded as a global amenity that should be readily available for anybody to experience?

The response of UNWTO and tourist operators is to regard overtourism as a management problem about the balance between competing interests, and to suggest strategies such as charging tourists, rationing access to major attractions, encouraging visits outside the peak season, and promoting other destinations (see this article in The Economist). However, as long as international travel is easy and inexpensive, and social media amplify the attractions of particular destinations, it is not clear that overtourism can be controlled. The likely result is that sense of place in the most popular destinations will be sacrificed to an other-directed veneer that satisfies visitors.

For tourist agencies and operators none of this seems to matter much, because they regard travel as wholly beneficial, a way to learn about other cultures. This is in line with the National Geographic argument that travel should be considered an essential human activity: “It’s not the place that is special, but what we bring to it and, crucially, how we interact with it. Travel is not about the destination, or the journey. It is about stumbling across a new way of looking at things.”

This splendid sentiment glosses over the fact that for many travel is a way to escape the humdrum, familiar places of everyday life. Moreover, for some rich nomads a new way of looking at things is based mostly on collecting places in order to brag about how many countries have been visited. For instance, the Most Traveled People club (one of several for place collectors) is for people who aspire to travel “Everywhere,” which is actually a list of 1500 places around the world, many of them obscure or difficult to get to. Place is thus reduced to little more than a push pin on the map of the world (see these two screen captures below from the MTP website).

Of course, some rich nomads do travel thoughtfully, do appreciate and learn from the places they visit. Nevertheless, mass tourism, bucket lists, collecting countries, all of which have intensified in the last two decades, suggest that international travel is turning many places into commodities to be consumed. And protests against overtourism are an indication that sense of place is at a tipping point as the everyday experience of being attached to a place is displaced by place collection for outsiders.

Poor Nomads are Placeless People

At the opposite end of the spectrum poor nomads, like many rich nomads, experience places in passing, but on the ground, on foot or by whatever inexpensive means can be found. Their experiences begin not with websites and brochures and cut-rate flights, but with the trauma of being uprooted, displaced by conflicts, political repression, drought, or some other event that has made life in their home place intolerable. For them travel is dangerous and arduous, involving violence, exploitation, risks of death, constant uncertainty about what might come next.

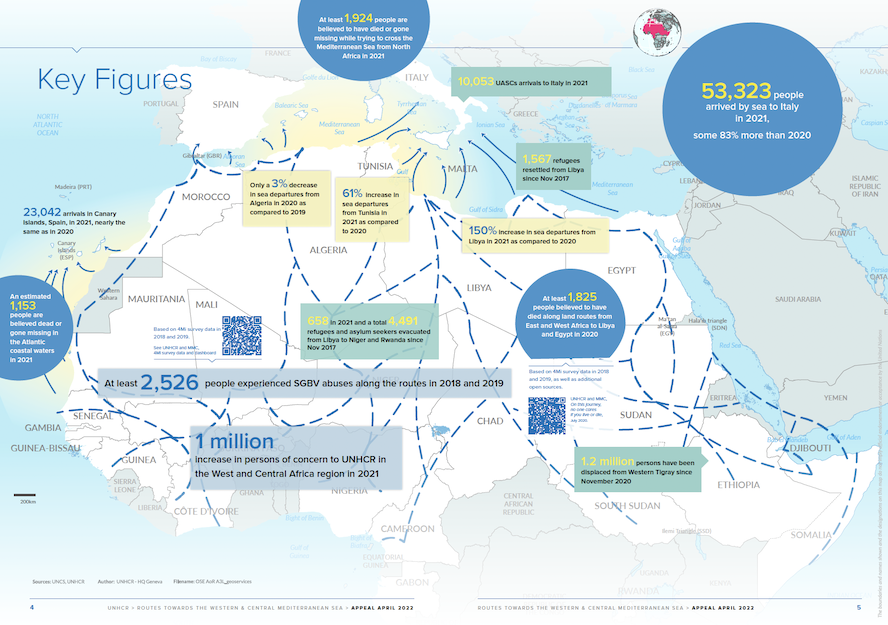

These challenges are apparently outweighed by the possibility of getting to somewhere that offers some hope for the future, preferably in one of the developed countries. Particular places encountered on the way are to be coped with and passed through as quickly as possible. For those heading to Europe the Sahara Desert and then the Mediterranean are very difficult and dangerous, in 2023 probably 270,000 attempted the crossing and about 10,000 are thought to have died. The Darien Gap in Panama was long considered to be impassable because of its mountains, jungles, poisonous snakes, and rough rivers. Yet hundreds of thousands, many of them families with children, are now attempting to cross it every year in a desperate effort to get to United States (see this recent account in The Atlantic about “Seventy Miles in Hell ).

Lyndsey Stonebridge, in an authorative book on the rise of refugee movements in the 20th century, describes refugees as “placeless people.” When they cross the frontier of their home country they become effectively placeless and stateless, and lose their rights as citizens and persons. Many end up in placeless refugee camps or asylum centres, often located in remote areas of a foreign country that may not even be legally part of that country, where they are condemned to be outsiders (see, for example, Kari Burnett, Feeling like an outsider: a case study of refugee identity, and Guntars Emerson et al, “Refugee Mental Health and the role of place in Global North Countries).

International refugees get most media attention, but well over half of all poor nomads are people displaced within their own own countries. These too have been “forcibly displaced” (UNHCR’s term to describe the coerced mobility of people who have been uprooted and forced to move as a result of warfare, persecution, conflict, violence, extreme weather). Wherever they travel or try to resettle they are likely to be more or less unwelcome, out of place, outsiders, even though they are nominally still citizens of in their own country.

A Concluding Comment about the Prevalence of Different Forms of Displacement

While I was writing about rich and poor nomadism I began to see both of them as manifestations of displacement, which in its various forms has become a significant aspect of how place is experienced in the 21st century.

Forced displacement as a consequence of conflict and repression has been extensively researched as a consequence of social injustice and repression. (See for example, Adey, P, et al, eds, The Handbook of Displacement, Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 2020; chapter summaries available here). But from the broader perspective of sense of place displacement applies to a range of apparently dissimilar events and experiences. The sense of place associated with both poor and rich nomadism has in common some degree of cultural outsideness and disconnection from the places where people were born and grew up.

This is obvious when displacement has been coerced. For tourists spending a few days or weeks away from home, for expats who choose to live in a foreign country, for guest workers, students studying abroad, and migrants, the displacement is voluntary chosen perhaps because it offers some excitement and a challenge. But it still involves disconnection and the experience of being an outsider, of not fully belonging somewhere.

I recognise that displacement is is not a new phenomenon, people have always traveled for pleasure, trade and discovery, moved to other places in other countries, and been uprooted by wars, oppression and environmental disasters. However, now, in the 21st century as rich and poor nomadism continue to grow, as climate change makes more and more parts of the world unliveable, attachments to places have become increasingly tenuous, not necessarily broken but weakened, and displacement is becoming the prevailing sense of place.

[I intend to dedicate a future post to the notion of displacement.]

Adey, P, et al, eds, 2020 The Handbook of Displacement, Palgrave Macmillan Cham, 2020;

Attali, Jacques, 1990 Millenium: Winners and Losers in the Coming World Order, Times Books, Random House, New York.

Stonebridge, Lyndsey, 2018 Placeless People: Writings, Rights and Refugees, Oxford University Press