Around 1990 there were two important events that have had growing implications for places. The establishment of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change in 1988 brought global warming to widespread public attention. And in 1989 Tim Berners-Lee invented the world wide web, which opened the door for the global expansion of the internet.

I discuss these at the end of this post. But first, and more briefly (because I have I discussed aspects of them in previous posts on this blog) I describe other recent trends that have affected ways of understanding, promoting, making, and experiencing places. Most seem to have grown exponentially since 1990.

The remarkable rise of academic interest in place

Since the 1990s the formerly esoteric interest in place has seen a veritable explosion in academic disciplines, including architecture, anthropology, business, geography, psychology, literature, art, political science, neuroscience, ecology, sociology, urban design and planning, and archaeology. It’s impossible to survey it all, but my sense is that much of the research is theoretical though some has spilled over into place practices and policies, perhaps most obviously place branding and placemaking. This dramatic increase in research and publication lies in the background of recent trends that have affected places.

Numbers of peer reviewed publication by decade that refer in some way to place and sense of place, as counted by ProQuest The International Bibliography of the Social Sciences.

| 1960-69 | 1970-79 | 1980-89 | 1990-99 | 2000-09 | 2010-2019 | |

| Place | 476 | 801 | 2,473 | 56,858 | 167,538 | 210,722 |

| Sense of Place | 222 | 192 | 483 | 28,815 | 80,482 | 90,811 |

Place branding (see my post here)

The practice of promoting places to attract visitors or new residents has a long history. In the 1990s, in the context of neo-liberalism and competition between world cities and other places to attract investment, it came to be called ‘place branding’, a term that captures its relationship to advertising and product branding. It involves the creation of slogans, logos, website design and marketing strategies to attract investors and tourists, and also aims to generate identity with place among residents. Most cities, regions and universities have now been place branded, and there are numerous consultancies, journals, and even an academic Institute of Place Management (defined as “a coordinated, area-based, multi-stakeholder approach to improve locations”) devoted to both place branding and placemaking.

Placemaking (see my post here)

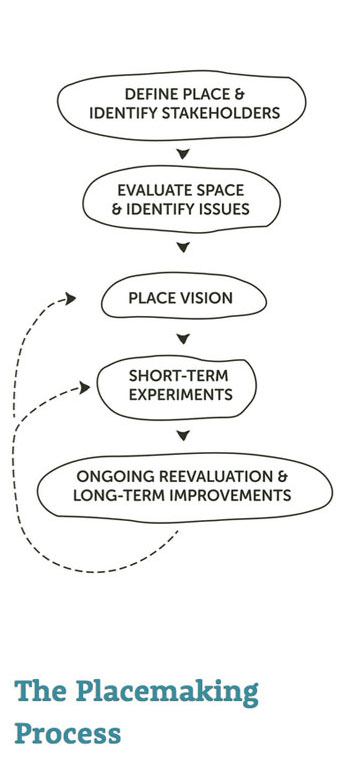

I have used the term ‘placemaking’ in this series of posts in a broad sense to refer to ways places have been built over the last two and half millennia, including architecture, plans, infrastructure, beliefs and world views. However, the term was rarely used before the 1990s, when it came to be used variously to refer to approaches that express suppressed identities of ethnic groups, to ways people transform the environments in which they find themselves into places where they live, and to the socio-economic production and reproduction of places. The American consultancy Project for Public Spaces, which considers itself the central hub of the global placemaking community (and is the source of the image on the right), provides a definition of how it is most commonly understood: “Placemaking is both an overarching idea and a hands-on tool for improving a neighbourhood, city or region.” It is along these lines that placemaking has become a widely used idea and practice in planning, urban design and development.

Non-places (see my post here)

In the 1960s Melvin Webber wrote about the “non-place urban realm,” by which he meant communities, such as those of academic, professional or business groups, formed around shared interests rather than around proximity and propinquity. In 1995 French anthropologist Marc Augé’s book Non-Places: Introduction to the Anthropology of Supermodernity expressed a different idea – that non-places are the parts of modern built environments without history, culture, or residents, such as hospitals, expressway service stations, shopping malls and airports. In these non-places experiences are contractual and temporary because we are patients, customers, have bought a ticket and are passing through on our way somewhere else. They are convenient, efficient, and largely anonymous because they have to be comprehensible to people with diverse backgrounds. They are essential in a mobile society.

Mobility, Overtourism, AirBnB

Mobility broadens experiences and reduces parochialism, yet also contributes to the need for non-places and weakens long-term commitments to particular places. The increased mobility that began with railways, and was dramatically reinforced by the invention of motor vehicles and airplanes, has continued to accelerate since 1990 at rates that far exceed population growth. The number of motor vehicles per capita has risen in all parts of part the world since 2005 (140% increase in Asia, 35% in Africa, 9% in Europe, 6% in North America). In short, more people everywhere are driving more, and place experiences involve views through windows.

Global Increases in Mobility 1990-2019.

Sources: Motor Vehicles OICA; Air Passengers World Bank; Tourists UNWTO; Cruises Cruising

| 1990 | 2019 | Percent growth | |

| Population | 5.30 billion | 7.70 billion | 45% |

| Motor Vehicles | 0.80 billion | 1.3 billion | 62% |

| Air Passengers | 1.0 billion | 4.2 billion | 420% |

| International Tourists | 425 million | 1.5 billion | 353% |

| Cruise Passengers | 3.7 million | 30.0 million | 810% |

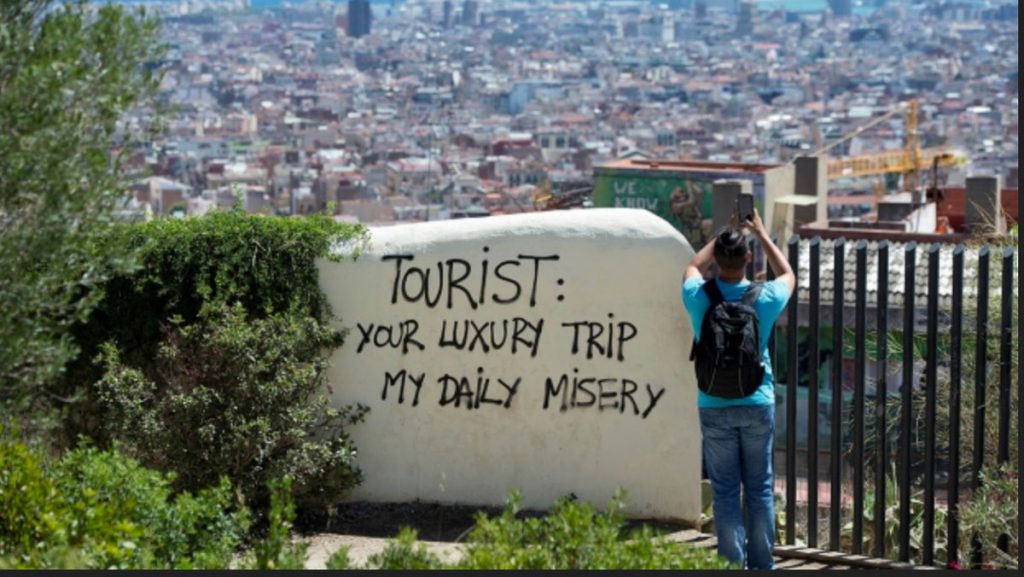

These increases in travel and tourism have led to serious overcrowding in popular destinations. Even before 1990 World Heritage Sites were experiencing problems, but since then entire cities, especially in Europe (Barcelona, Dubrovnik, Paris, Berlin, Rome, Venice, Bruges, Prague, Cambridge, Amsterdam, etc), have been overwhelmed by what, since about 2015, has been called overtourism. Places experiencing overtourism are diminished to something like a blend of theme parks and non-places, and the place experiences of tourists are reduced to glimpses through crowds and brief opportunities for selfies.

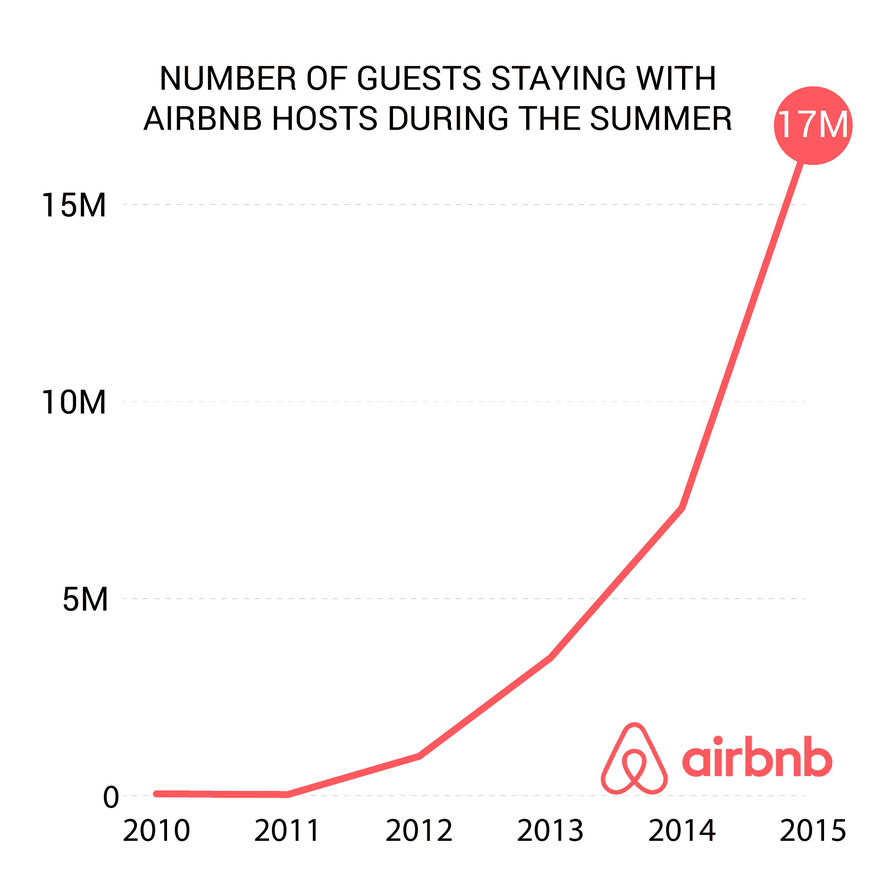

The explosive growth of Airbnb since it was founded in 2008 as a modest attempt to enable travellers to connect with hosts through the internet, has played a role in this. By 2019 it had 500 million listings in 191 countries and 81,000 cities. Airbnb’s mission is in part to create “a world where anyone can belong anywhere…” in other words to make all places equally accessible. Its international success has, however, contributed to local housing shortages and pushed up housing costs as its listings have displaced conventional rentals. While Airbnb has enhanced place experiences for travellers, it has undermined place experiences of residents unable to find accommodation or paying inflated rents.

Electronic Media and Places

Airbnb, and indeed all the booking, control and GPS systems that make current international travel affordable as well as possible, owe much of their success to the invention of the world wide web in 1989 by Tim Berners-Lee, whose intention was to create “an open platform that would allow everyone, everywhere, to share information, access opportunities, and collaborate across geographic and cultural boundaries.” In other words, to make all places equal for communications. Electronic media had been shrinking and permeating the world since the invention of the telegraph in the 1840s, but this had happened from the top-down through institutions, corporations and broadcasters. The web passed that ability on to individuals, making us all potential producers of media, who can share information regardless of where we happen to be.

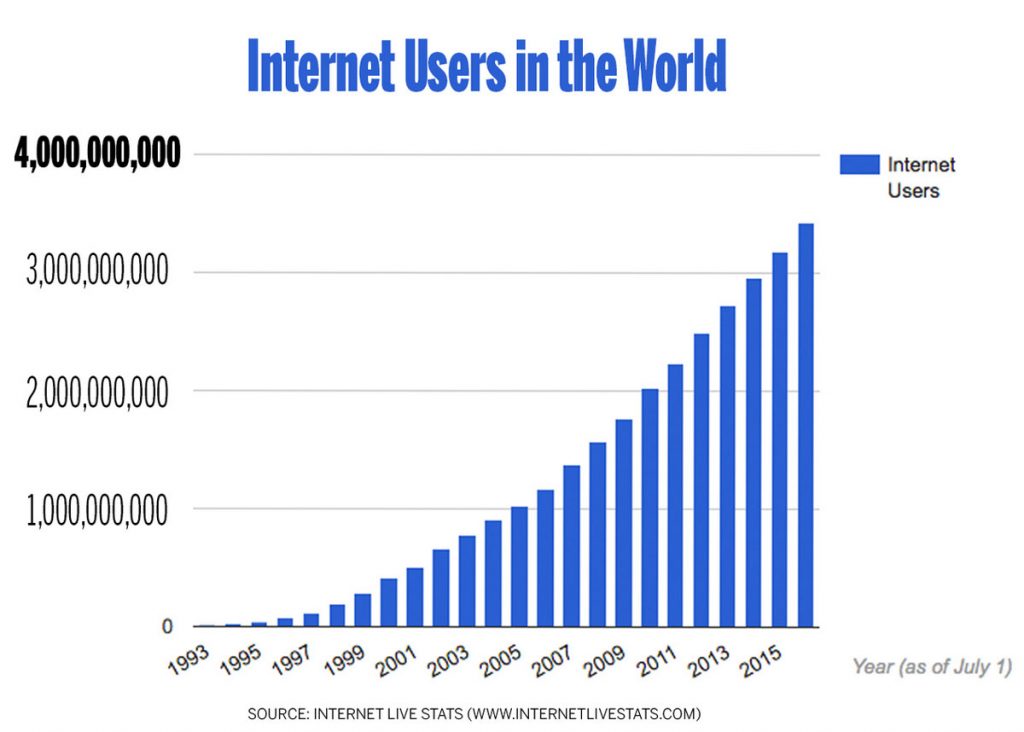

The web was supplemented by search engines (Google late 90s), social media platforms (Facebook 2004, YouTube 2005) and smart phones (iPhone 2007). Together these opened a floodgate. In 1990 there were few million internet users, mostly in universities; this has now grown to 4.5 billion active users spending an average of about 3 hours a day online. A change of behaviour of this magnitude has to have had an impact on places. But, as is known from the introduction of printing, the initial effects of innovations in communications media on the physical character of places can be slight, even though their long-term social and experiential effects might be profound. The dramatic popularization of electronic media is so recent and still in process that its effects are open to diverse interpretations.

First of all, it is worth noting that the direct impacts of electronic media on the forms and appearance of places have so far been incremental – poles, wires, satellite dishes, buried cables, wireless signals that leave all existing built forms mostly as they were. Built forms seem to be have been scarcely affected.

Electronic media have changed experiences of places, though exactly how is open to interpretation. At the most personal level Sharon Kleinman refers to the consequences of talking on mobile phones in public spaces, scarcely aware of what is around us, as “displacing place.” On the other hand, it has been suggested that locative media (smart phones, tablets), which always know our location, can combine immediate experience with online data about the place we are in, for instance about wayfinding and amenities, in effect drawing information into and out of a place in ways that enhance experiences of places.

At a larger social scale Joshua Meyerowitz argued in his book No Sense of Place, that “Where one is, has less and less to do with what one knows and experiences.” In other word social relationships are no longer dependent on local communities. The web has no landscape and no geography and the communities that form there are non-place communities formed on the basis of shared interests. These can be short-lived, sometimes generating so-called “smart mobs” of people who don’t know one another yet react compulsively to online memes about events or attractions, and this can lead to behaviour that spills over into real places, such as tens of thousands turning up to take selfies in a place where wild flowers bloomed in a spectacular way in California in 2019. Smart mob behaviour may also lie in the background of overtourism, prompted by websites that promote iconic tourist attractions.

More positive manifestations of non-place communities that impact actual places include, perhaps ironically, the Città Slow movement that began in Italy as way to celebrate local food and culture, and is now an interconnected global phenomenon. City Mayors is an online network that http://www.citymayors.com/ promotes “good, open and strong local government” by enabling cities around the world to learn from each other and act together. However, non-place virtual communities also form around anti-social, prejudicial convictions that are amplified in on-line echo chambers and filter bubbles. These, too, can spill over into real world behaviours, such as acts of terrorism and attacks on mosques and synagogues.

A more direct manifestation of the role of electronic media in places occurs in attempts to design “smart cities”, such as that by Sidewalk Labs, a subsidiary of Google, for a neighbourhood in Toronto that will be monitored with “data integration that provides ubiquitous connectivity for all” and claims to be “creating a new type of place to accelerate urban innovation and serve as a beacon for cities around the world.” Critics of smart cities, and indeed of Google and the entire tech industry, see them as engaged in data gathering that involves constant surveillance and invasion of privacy. Many cities (especially in China) are now festooned with security cameras, some using facial recognition technology, ostensibly for security (Shenzen has 159 cameras per 1,000 residents, London 68, Atlanta 16, Singapore 15). It seems likely that places in the future will be data collection machines, but whether this will be for surveillance or to improve urban management is not so clear.

More than fifty years ago Marshall McLuhan, who is perhaps most famous for coining the idea of the global village, wrote presciently about the social impacts of electronic media. He thought that the outcome of electronic communications, which circle the world at the speed of light, compress time and space and “turn the world back in on itself in a global embrace,” would be that person-to-person relationships take on the emotional and social characteristics of oral cultures as if in “the smallest village.” The global village, he suggested, was not so much an electronic melting pot (which is usually how the phrase is used), but filled with trivial electronic gossip from elsewhere, often abrasive and where personal concerns and emotions get magnified. It is, in effect, superimposed on the countless material places inherited from previous centuries when rational ways of thinking associated with print media prevailed. Skyscrapers, suburbs and megacities are not easily changed, at least in the short run. What are upset are ideas of history, geography, truth, reason and the ways we experience places. In the global village it seems that the significance of places as discrete, material entities has been diminished and compressed.

“In the age of the speed of light what cropped up yesterday, here and there, now happens everywhere at once…there is no longer ‘here,’ everything is ‘now.’” (Paul Virilio, 1997)

Climate Change and Places.

The creation of the IPCC (International Panel on Climate Change) in 1988 vaulted climate warming from a mostly scientific issue into a matter of broad concern. It is widely expected to be the critical environmental, social and economic problem of the 21st century. It has considerable implications for places.

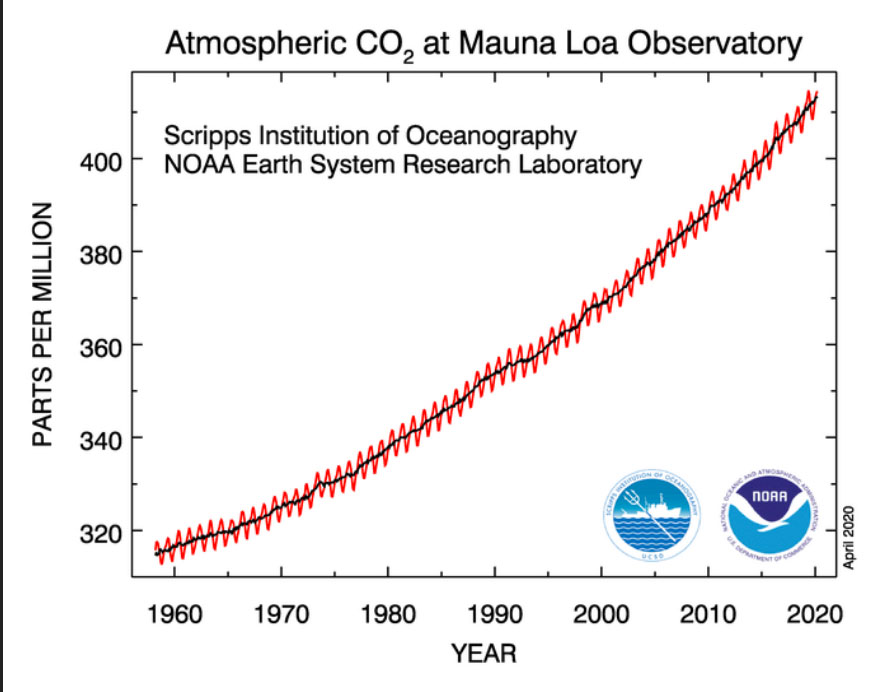

The trend which triggered awareness in 1988 of global climate change was the steady increase in atmospheric CO2 measured at a particular place – the Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii. The trend continues. (Source: https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/webdata/ccgg/trends/co2_data_mlo.png). On the right, the dome of Mauna Loa shield volcano is in the background; Kilauea, which erupted in 2018, is smoking in the middle-ground.

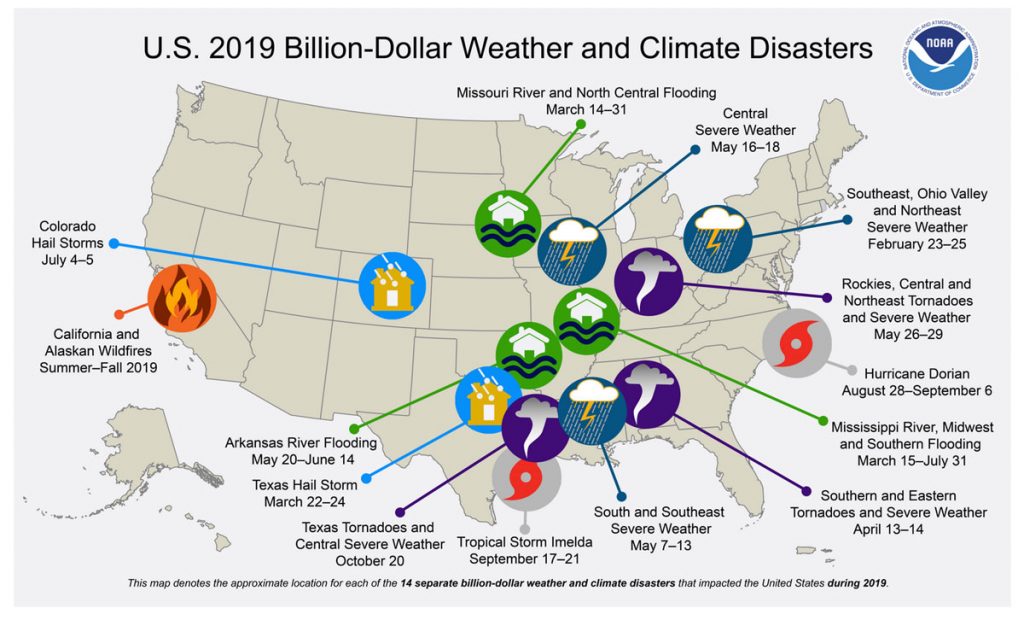

Some of those implications are epistemological. Climate change requires that all places be considered simultaneously as locally distinctive (because the increasingly intense weather events it causes are local) and globally interconnected (because all places contribute to and share the atmosphere of the earth). Furthermore, its rapid onset has converted what was formerly a background longue durée factor for places into into short-term intense weather events – coastal and river floods, severe droughts, wildfires, tropical cyclones –that are impacting places, and demand immediate place-based responses.

Although responses to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions and to adapt to impacts of changing weather may be directed by national or regional policies, their implementation is necessarily local. And if national governments, notably the United States, choose to ignore climate warming, local municipalities cannot afford to be so ideologically myopic and are building flood walls, requiring energy efficient buildings, expanding urban forests, instituting water conservation, providing cooling centres. and acting proactively to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, numerous mayors and local municipalities participate in global networks to share experiences and practices.

In short, many places are already being retrofitted and modified to respond to the local environmental challenges presented by climate change. This is consistent with recommendations in Global Warming of 1.5C the 2018 special report of the IPCC that focuses on measures needed to keep warming below that level. This report explicitly and repeatedly uses the language of places to describe strategies for mitigation and adaptation. It recommends that: “Pursuing place-specific adaptation pathways towards a 1.5C warmer world has the potential for significant positive outcomes for well-being in countries at all levels of development” (5.3.3).

These pathways have to acknowledge the various scales of places, different groups involved in them, uneven power structures, historical legacies, and the local priorities and trade-offs that shape the sustainability and capabilities of everyday life (5.3.3). For much of the mid-century urban populations will grow by 70 million people a year, and “Cities are places in which the risks associated with warming of 1.5C , such as heat stress, terrestrial and coastal flooding, new disease vectors, air pollution and water scarcity, will coalesce.” (4.3.3.3). In other words, the diversity and distinctiveness of places is critically important – one set of climate actions will not work everywhere.

Keeping global warming below 1.5C will not be easy and could require both transformational adaptations ( i.e more than incremental modifications to existing practices) and disruptive innovations that will have to be related to the communities, location, context and vulnerability of specific places (4.2.2.3). Indeed, while responses have to be coordinated between all levels of government – international, national, regional and municipal – to be effective, “progressive localism” is especially important because the “proximity of local governments to citizens and needs makes them powerful agents of climate action” (Cross Chapter Box 13, Cities and Urban Transformation).

A Note on the Coronavirus Covid-19 Pandemic and Places

Previous epidemics, even though their social consequences might have been great, do not appear to have had long-term impacts on how places were made or experienced. While the Covid-19 pandemic may follow this pattern, there are indications, even as we are the midst of it, that it has interrupted some trends that have been affecting places and has reinforced others.

It has interrupted the upward trend in international travel and tourism. This will persist as long as travel restrictions remain, which is likely to be until a vaccine is widely available, perhaps in two years. While this immediately reduces problems of overtourism, it will also undermine the economies of places dependent on tourism.

Mark Carney, the former governor of the Bank of England, thinks travel restrictions will accelerate the fragmentation of the global economy with the effect that “local resilience will be prized over global efficiency.” If so, this will reinforce a background trend to localism that has been underway for some time (see my post here). This would be supplemented by increasing local tourism, possibly aided by initiatives in place branding and placemaking and the “progressive localism” recommended the by the IPCC as an essential part of any strategy for climate action.

The pandemic has led to a surge in the use of electronic communications both as the preferred means for getting local and international news, and for establishing versions of non-place communities for social interactions on Zoom, and for working at home. If the latter turns out to be productive it will have implications for the need for offices and commuting. Proposals for using mobile phones for for tracing contacts have raised concerns about surveillance that will make all places part of an electronic panopticon.

More generally, the pandemic has brought into the spotlight the interconnections between global processes and their consequences in the places where we live. Climate change is a slower-moving version of these interconnections and consequences, potentially with even more devastating outcomes. In this respect, the novel coronavirus, is both a cause of immediate disruptions and suffering, and a wake-up call about the necessity of taking early actions to mitigate global disasters whose consequences are visited on everyday lives in particular places.

References

Marc Augé 1995 Non-Places: Introduction to the Anthropology of Supermodernity, Verso

Sharon Kleinman (ed) 2007 Displacing Place: Mobile Communication in the Twenty-First Century, Peter Lang

Marshall McLuhan 1964 Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man, Signet PressJoshua Meyerowiz 1985 No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behavior, Oxofrd University Press

Paul Virilio 2000 Landscape of Events, Cambridge University Press