The past and the future are places

Place is infused with time. Indeed, from perspectives such as those suggested in these two illustrations, place and time are apparently the same thing. The future is a place, and the past is a place. (Carillion was a British construction companym working around the globe. Stephen Harper is a former Prime Minister of Canada, and this quote is from an interview in 2016 after he had lost an election and had resigned. Note: Carillion declared bankruptcy at the beginning of 2018. Tomorrow, it seems, was not a better place. )

More conventionally we usually think of ourselves as living in places in the present, looking toward the future with the past behind us. This conforms with the abstract idea of time as a linear flow in which we are immersed as though in a river, a conviction that has long prevailed in English speaking cultures and is implicit in ideas of progress.

An exhortation to acknowledge temporality. This is on a small electrical junction box on a street in Victoria, British Columbia.

Temporality and alternative notions of time

This is, however, not the only way of thinking about time. In Ancient Greece people thought of themselves as having their backs to the future, never sure what was coming next, while looking back to the relative certainties of the past. And according to the physics of relativity time is not smoothly linear, but distorted by motion and gravity. Similarly in our everyday experiences of places time is neither constant nor linear. What we experience is “temporality,” a continually shifting blend of memories and things inherited from the past, intentions, expectations, and occasional moments of dejà vu. (The idea of temporality has several origins, one of which is of particular importance to students of place – Heidegger’s Being and Time).

Time-Places

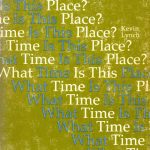

In his book What Time is This Place? Kevin Lynch investigates what he calls the “temporal collages” of superimposed pasts, present and future as they are manifest in built environments. He examines the diverse manifestations of time in cityscapes – clocks, parking signs, rhythms of movement such as rush hours, evidence of preservation and continuity in architecture, and various intimations of the future. His conclusion (p.241) is that: “…space and time, however conceived, are the great framework within which we order our experience. We live in time-places.” Time-places, he suggests, are consonant both with the structure of reality as we experience it, and with the nature of our minds and bodies. They are, in other words, manifestations of temporality.

In his book What Time is This Place? Kevin Lynch investigates what he calls the “temporal collages” of superimposed pasts, present and future as they are manifest in built environments. He examines the diverse manifestations of time in cityscapes – clocks, parking signs, rhythms of movement such as rush hours, evidence of preservation and continuity in architecture, and various intimations of the future. His conclusion (p.241) is that: “…space and time, however conceived, are the great framework within which we order our experience. We live in time-places.” Time-places, he suggests, are consonant both with the structure of reality as we experience it, and with the nature of our minds and bodies. They are, in other words, manifestations of temporality.

Ideas of past, present and future only come into the foreground when we choose to think about them or when we experience abrupt changes, for instance when familiar old buildings are demolished, our personal fortunes suddenly shift, or war or natural disasters destroy somewhere. Then the question arises of how places should respond to change. Should the old styles of buildings and streets be preserved, or is it more appropriate to replace them with something new? How are necessary additions and new buildings to be incorporated? These are questions of heritage conservation.

The Recent Origins of Heritage

In spite of its title and conclusion Lynch’s book is mostly about time rather than place, and it is mostly about the past because place-time collages are everywhere dominated by an enormous inheritance of names, street patterns, monument and buildings that are decades or centuries old. He discusses strategies of conservation, preservation and restoration for protecting these historical remnants. But he does not mention heritage.

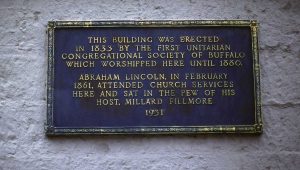

Pre-Heritage historical plaque in Buffalo, New York

From the current perspective of how to treat old cityscapes this seems like a remarkable omission, yet the reason for it is simple. The idea of heritage as we now think of it is a relatively recent one. Lynch’s book was written just before 1972, which was the year of a UNESCO Conference on the Protection of Cultural and Natural Heritage that brought the notion of heritage into popular attention. Before then heritage meant little more than family heredity, or perhaps putting a plaque on a wall to acknowledge that famous politician been born or visited there. There had been movements to restore significant old buildings, such as churches and castles, in the 19th century (Violet le Duc in France and Gilbert Scott in England), and buildings associated with famous politicians, such as their places of birth, were often protected and identified with a plaque. But none of this was called heritage, and there was no broad movement to protect what was old.

On the contrary, the origins of the modernist movement in architecture and planning were based in an explicit rejection of whatever was old and a celebration of the possibilities of the future. This attitude culminated in the practices of the 1950s and 60s, when architects, planners and developers took the opportunity to replace obsolete old buildings and districts with something modern, whenever the opportunity arose.

By 1970 the destruction of old places, environments and buildings began to be seen as synonymous with the destruction of the past, and the 1972 UNESCO conference was a response to this sense that things of great cultural value were being destroyed. The conference hoth established the idea of World Heritage Sites and encouraged participating nations to pass legislation to preserve and protect their own heritage sites. Most of them did. The result has been that since 1972 built heritage has become an integral part of city planning, a major attraction for tourism, a concept whose merits are assumed to be self-evident, and something that should be protected whenever possible.

Place and Heritage

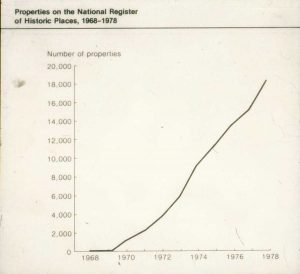

The number of properties on U.S. National Register of Historic Places, 1968-78, parallels the emergence and rapid take-off of interest in heritage preservation just before and after the 1972 UNESCO conference

This rise of interest in the protection of heritage is almost exactly contemporary with the rise of interest in and writing about place. This may not be altogether coincidental. One of the strongest motives for writing about place appears to be that both spirit and sense of place were much stronger in the past and now deteriorating. This is implicit in my own writing about place and placelessness, and in Marc Augé’s notion of non-place. It is explicit in the British RSA (Royal Society for the encouragement of the Arts) website on Heritage, Identity and Place, and the American National Trust for Historical Preservation website Saving Places. The consequence is that while it is possible to discuss place in theoretical and philosophical ways without much consideration of heritage, it is now impossible to consider the identities of geographical places with paying attention to their heritage.

While it is possible to discuss place in theoretical and philosophical ways without consideration of heritage or time, as much the theoretical literature demonstrates, it is now impossible to consider the identities of geographical places, to contemplate placemaking,or to plan or develop actual places with paying attention to their heritage. This poses problems, because for all its popularity and positive connotations, heritage is a very confusing idea.

Heritage is a Jumbled, Malleable Amalgam

David Lowenthal, who considers himself a devotee of preservation, has suggested that heritage has now become such a sacred cow that it few are willing to question it critically. While it is the basis for preserving artifacts, buildings and townscapes that have huge cultural and aesthetic merit, and identifies some links to our cultural roots that might otherwise be lost: “The heritage past is,” he suggests, “a jumbled, malleable amalgam.”

Heritage Town (the largest in America!) is a reproduction old-style Chinese food court on the second floor of Pacific Mall, a modern Asian shopping mall in Markham, in Toronto’s outer suburbs, in Canada. The photo on the right shows the tiled entrance gate underneath the exposed ducting of the modern building.

Heritage Town (the largest in America!) is a reproduction old-style Chinese food court on the second floor of Pacific Mall, a modern Asian shopping mall in Markham, in Toronto’s outer suburbs, in Canada. The photo on the right shows the tiled entrance gate underneath the exposed ducting of the modern building.

Heritage is not history, which explores and explains a past that has grown opaque over time. Instead it is the selection and clarification of bits of the past that somebody or some group has identified as important in order to infuse them with present purposes. Heritage distorts history for reasons of education, to attract tourists, or to promote some political agenda. Even when its practitioners strive for authenticity, for example by using the same sorts of tools and methods that were used in the original construction, heritage sites are fragment of an old time-place that are set apart and often fenced off from the time-place of the present.

Signs at the Oelsner Mound in Florida, and for a new housing development in Toronto.

Old European cities have a lot of potential heritage available for selection. New suburbs, even in Europe, not so much. In North America the heritage of First Nations was displaced by the imported heritage of British and other European colonists who systematically imposed the names and architecture and customs of the old country on the new one. Now many of the towns and landscapes those European colonists created are in turn being taken over by groups with entirely different cultural backgrounds. In Toronto, for example, Chinatown occupies streets with Scottish names, and South Asian communities live in districts with imported English names such as Scarborough..

The Horton Building in suburban Toronto is now part of a suburban Chinatown. Lever House, the first (1952) modernist skyscraper in New York City, undergoing restoration about 2001.

Furthermore, the cut-off dates for what constitutes heritage are steadily being moved closer to the present with paradoxical consequences. Modernism is a 20th century architectural ideology that was explicitly based in a rejection of the past and a celebration of the future, yet iconic modernist buildings, such as Lever House in New York and the Bauhaus are now preserved as important architectural heritage.

I don’t recall the source of this cartoon, which captures well some of the difficulties with heritage preservation.

The strange context of heritage preservation in the context of skyscraper condominiums in Toronto, from a planning document

A Critical Perspective

Heritage seen through the lens of temporality is not easy to unravel. Perhaps it is best regarded as no more than another manifestation of time in place that protects some aspect of landscape, or is a good example of an architectural style, or where something regarded as important happened. It usually involves some blend of nostalgia, aesthetics and supposed educational value, even if the less savoury and smelly aspects of the past are usually omitted. The essential question to be asked of all heritage preservation is whose heritage is being preserved. The achievements of the wealthy and powerful prevail over those who were oppressed and impoverished, in part, of course, because cathedrals and castles are invariably are architecturally more durable than tenements and hovels, but also because they represent positive accomplishments that we are expected to admire regardless of who was oppressed in order to make them.

The Practical Importance of Heritage for Places

Regardless of these theoretical equivocations about the jumbled arbitrary character of heritage, the practical fact is that heritage has, since the UNESCO conference in 1972, become an essential aspect of any places that have a history that can be traced back more than a few decades. The protection of heritage has become an essential consideration in urban planning almost everywhere. In many (perhaps the majority) of countries it is a legal requirement. It is a powerful basis for arguing against new developments that might otherwise ignore local history and contexts and for maintaining whatever remains of the older identities of places. Local heritage organizations research local history, identify building and sites that can be considered significant for architectural or other reasons, advise local planning departments and councils, and constitute a lobby to ensure that the past in places is not forgotten.

It is now impossible to discuss particular places without considering their heritage. And I admit that I really enjoy much of what has been accomplished through heritage protection. It slows down development and encourages thoughtful consideration of the merits of old landscapes and buildings. On the other hand it is wise to remember that heritage designation is frequently arbitrary and not always beneficial. For private homes it can result in increased insurance and maintenance costs that are beyond the owners means; for business properties or institutions it can limit changes that are needed to keep them economically viable, a particular concern for churches with declining congregations. The only options then are to apply for de-designation, or, more drastically to let somewhere to decay in place so that it can be demolished and redeveloped. Designation as a World Heritage Site is both a wonderful accolade and a potential curse because it turns somewhere into a global tourist magnet, attracting tour buses and cruise ships and gift shops and fundamentally changing the character of the place it is meant to protect from change.

Crowds at the Parthenon in 1990, which was being renovated and sprayed (by the man in the red shirt) with a chemical to prevent damage from air pollution

A marker for a vanished place, all that remains of Amulet in Saskatchewan, a small settlement with school, banks, a hotel, grain elevators and houses that existed from 1910 to 1973.

In short, for all its benefits, heritage preservation poses problems for the identity of places. ”Restoration.” exclaimed the nineteenth century English art critic John Ruskin, “is the most palpable damage a building can suffer.” All attempts at restoration and preservation are attempts to stave off the passage of time. In his remarkable book How Buildings Learn, Stuart Brand reminded us that change is a fundamental aspect of architecture – buildings, at least the ones that have not been designated, are added to and modified as fashions and needs shift. This is no less true of neighbourhoods and cities. All places are in fact time-places and expressions of temporality in which continuity and change are always present in a state of tension. Fragments of time-places can be set aside for protection, but everything cannot be protected and the larger context of place will continue to change.

Brand. Stuart, 1995 How Buildings Learn: What Happens after they are Built, Penguin

Lowenthal. David, 1996, Possessed by the Past: The Heritage Crusade and the Spoils of History, Free Press

Lynch, Kevin 1972 What Time is this Place? MIT Press