An advertisement for an art exhibition at the Sturt Gallery in Sydney in 2014

Places have been remarkably dependable sources of inspiration for poets. Poetic accounts of places imagined or real are to be found throughout the history of Western civilization – Homer’s Odyssey, Virgil’s poems about farms and farming, Dante’s Inferno, Wordsworth poems of the English Lake District and T.S. Eliot’s The Wasteland. At least two recent books of poems are simply titled Place (one by Allen Fisher, and the other by Jorie Graham).

Conversely, poetry offers insights for those whose main interest is in place,. Alexander Pope’s 18th century advice to wealthy landowners about landscape gardening to “Consult the genius of the place in all” is frequently quoted (including by me in the post on Spirit of Place on this website). Martin Heidegger, arguably the pre-eminent philosopher of place, drew frequently on poetry, especially that of Hölderlin, to inform his thinking. The geographer Tim Cresswell, who wrote Place: A short introduction about the role of place in academic geography, is also a published poet and has recently completed a thesis about “topo-poetics,” which I discuss below.

The connection between place and poetry is strong, diverse and bilateral. In this post I offer some brief, tentative thoughts on this connection, mostly by drawing on observations made by poets writing about place.

Poetic Observation and Imagination

Owen Sheers in his essay “Poetry and Place: some personal reflections” suggests that: “A poem like landscape, situates us by translating the abstract world of thought and feeling into a physical language.” His essay is illustrated with photos of Welsh mountains, so by “physical language” I think he means a language that responds to the carefully observed characteristics of a particular place yet makes imaginative connections with broader feelings and ideas.

Almost two centuries ago the Victorian art critic John Ruskin identified three forms of imagination that occur in both painting and poetry. Associative imagination selects things and ideas to compare and combine, putting them together in original ways both truthful and revealing. Penetrative imagination “seizes its materials… gets down to the root, and drinks the very vital sap of what it deals with.” Contemplative imagination conjures up distinctive images mostly from memory. Every great conception of a poet or painter is touched by these forms of imagination, which, Ruskin claimed, follow from seeing the world clearly. Poor poetry, on the other hand, lacks these forms of imagination, uses borrowed or contrived images, and “plays like a squirrel in its circular prison.”

It follows, I think, that good poetry of place sees significance in things and landscapes to which most of us would pay scant attention, and embodies the imagination needed to draw unexpected associations that amplify this significance. Here’s a brief example from Wallace Stevens’ “Anecdote of the Jar” (quoted by Tim Cresswell in his thesis on topo-poetics):

I placed a jar in Tennessee,

And round it was, upon a hill.

It made the slovenly wilderness

Surround that hill.

The wilderness rose up to it,

And sprawled around, no longer wild.

Specificity and intersubjectivity of place experience in poetry

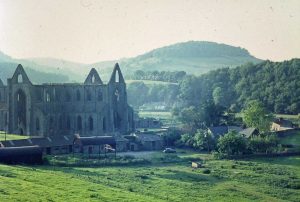

A more substantial example of the role of imagination in place poetry is William Wordsworth’s “Lines composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey, on revisiting the banks of the Wye during a tour,” written in 1798. This has autobiographical significance for me because I grew up in a small community located on the hills a few miles north of the village of Tintern, no more than a few miles from where he must have conceived his poem.

Tintern Abbey about 1970. The River Wye is just to the right of the abbey, but out of sight. This view had scarcely changed when I last visited in 2016. I grew up somewhere behind the hill in the background.

Neither Tintern Abbey nor the River Wye is mentioned except in the poem’s title, yet Wordsworth’s descriptions of “steep and lofty cliffs,” “plots of cottage ground,” “hedge-rows, hardly hedge-rows, little lines/ of sportive wood run wild,” and “pastoral farms,” evoke the specific character of the Wye valley and make it recognizable even to those who may not be familiar with it. This poem, like many poems of place, is in other words, communicates intersubjectively; it is simultaneously about somewhere particular and has a widely shared resonance.

This quality is deepened because Wordsworth then contemplates how he owes to “these beauteous forms” memories of when he was last here, recollections that offer him “tranquil restoration” and lighten “the weary weight of all this unintelligible world.” And he then reflects on how his experiences of the world have changed as he has matured and makes the chastening imaginative association that has informed much of my own thinking about place and landscape:

For I have learned

To look on nature, not as in the hour

Of thoughtless youth; but hearing oftentimes

The still sad music of humanity,

Nor harsh, nor grating, though of ample power

To chasten and subdue.

“Lines composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey” is, in effect, a concise yet profound phenomenological disclosure of the character of place experience, beginning with description, imaginatively engaging with memories, and disclosing how experiences of a particular place can open into cosmopolitan understanding.

Obviously this sort of imaginative insight is not achieved in all poems about places, perhaps only in a few, but it is perhaps a common intention. James Galvin has a distinctive take on what this involves from the perspective of a poet. “The poet of place,” he writes, “situates himself in place in order to lose himself in it. The poetry of place is actually a poetry of displacement and self-annihilation.”

Screen capture of the map of the Seattle Poetic Grid, showing locations of poems about places in the city.

Localization rather than Globalization

Poetry has a powerful capacity to evoke particular places, to inform us of their meanings, and in effect to ground us in them regardless of whether know them or not. This is in part the inspiration for the Seattle poetic grid created by Claudia Castro Luna, the city’s civic poet. This grid consists of poems about particular places in Seattle, the locations of which are shown on an interactive online map. Luna writes on the home page that the poems trace the city through the voices of its citizens because “we live in the city and the city lives in us.”

Windfall: A Journal of Poetry of Place publishes poems that capture the spirit of place, including its history of human presence, as part of the essence of the poem. The journal is, the editor claims, about localization rather than globalization, but the poems are also selected because they challenge the tendency of much modern poetry to turn to interior states of mind in which the external world is incidental.

I fully endorse the quotation on the home page of Windfall from Scott Russell Sanders: “Many of the world abuses of land, forest, animals and communities have been carried out by people who root themselves in ideas rather than places.” This view is echoed in the themes to which each issue of Windfall is dedicated (and which are elaborated in informative Afterwords). These themes include commuter and in-between places, cemetery places, peak oil, global warming and the poetry of place, dwelling in place, and most recently the political poetry of place (which considers fake news). The poetry of place may be local and grounded, but that does not mean it cannot address broad social and environmental issues.

I fully endorse the quotation on the home page of Windfall from Scott Russell Sanders: “Many of the world abuses of land, forest, animals and communities have been carried out by people who root themselves in ideas rather than places.” This view is echoed in the themes to which each issue of Windfall is dedicated (and which are elaborated in informative Afterwords). These themes include commuter and in-between places, cemetery places, peak oil, global warming and the poetry of place, dwelling in place, and most recently the political poetry of place (which considers fake news). The poetry of place may be local and grounded, but that does not mean it cannot address broad social and environmental issues.

Topo-Poetics

From his dual perspective as geographer and a published poet, Tim Cresswell coined the term topo-poetics to distinguish an approach that conveys the myriad ways in which people dwell in places. The notion of dwelling comes from the philosopher Martin Heidegger, much of whose thought has been shown by Jeff Malpas to be a disclosure of the essential role of place in being, a role that Malpas describes as topology. Topo-poetics differs from geo-poetics and eco-poetics two other approaches to poetry that responds to the earth and its environment, both because of its explicit attention to place and places, and because it acknowledges that a poem about place is in some degree itself a place.

This latter idea is also partially derived from Heidegger, and Cresswell (p19) cites Heidegger’s observation that: “Poetic creation, which lets us dwell, is a kind of building.” He then suggests that a poem about place is itself a place and constitutes a form of place-making created by its very presence on the page surrounded by blank space that is outside it.

Cresswell develops these ideas through interpretations of the work of American poet Jorie Graham, who has a book of poems simply titled PLACE; Elizabeth Bishop, who has books of poems called Questions of Travel and Geography III; John Burnside’s poetry of betweeness that explicitly drew on Heidegger’s ideas of dwelling; and Don McKay, whose poems develop a phenomenology of natural landscape through what he called “poetic attention.” Cresswell’s thesis in part required creative writing, and it concludes with a number of his own topo-poems that reflect his own understanding of place and which, he suggests, stress displacement.

A shifting sense of place

A lot of place poems are about bucolic and natural places. They have a tone of what might be described as enduring rural felicity. Contemporary poets, including Cresswell, take a more inclusive view of the modern world with all its comforts and challenges. When C.D.Wright was asked about her sense of place, she replied that it is phrase that she feels is “quite drained of significance,” but she nevertheless writes about actual places because they are “so real”

.Jeremy Richards describes this sort of sensibility as a “shifting sense of place.” He suggests that a classic poet could stroll through a garden, stumble past a church, or kneel in the grass and feel sated and grounded. But today, he asks, “where is the poet’s sense of place? Itinerant, polluted, untethered? Tweeted?” Good questions when so much seems to changing and on the move. Here is Shelley Kirk-Rudeen writing about changes in Zumwalt Prairie in eastern Oregon:

There will be no one place to call home.

Everything on the move, leaving

To become native to new places

As the old homes change.

bell hooks, a well-known poet and writer who grew up in a remote area of Appalachia about which she has written several books, says simply that her identity is firmly rooted in a place that is no longer whole. Poets of place, at least those who combine careful observation with imaginative insights, do not merely celebrate place. They recognize that all places offer comforts and challenges and that these are constantly shifting.

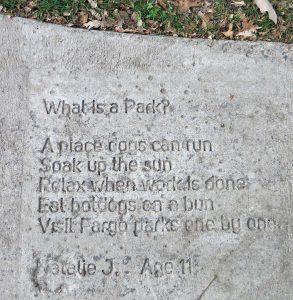

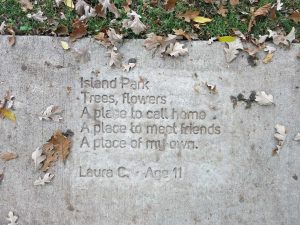

Two place poems by 11 year olds in place in Island Park in Fargo, North Dakota. There is a National Writing Project in the United States that provides a template for school students to write place based poetry. I don’t know whether these poems are a product of this but they certainly illustrate the broad appeal of the poetry of place.

References

Cresswell, Timothy, 2004, Place: a short introduction (Oxford: Blackwell)

Cresswell, Timothy 2015, Topo-poetics: Poetry and Place, Royal Holloway University of London, Doctoral Thesis in English-Creative Writing, at https://pure.royalholloway.ac.uk/portal/files/25313757/Complete_poems.2015.final_signed.pdf

Fisher, Allen, 2005, PLACE, Hastings, East Sussex, Reality Street Editions

Galvin, James, “The Poetry of Place: James Wright’s ‘The Secret of Light’ at https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/collection/poetry-and-place

Heidegger, Martin, 1975 Poetry Language Thought Harper and Row

hooks, bell, 2012, Appalachian Elegy: Poetry and Place University Press of Kentucky

Kirk-Rudeen, Shelley, 2006 “Zumwalt Prairie” in Windfall: A Journal of Poetry of Place accessed at http://www.hevanet.com/windfall/poetryofplace.html

Malpas, Jeff, 2006 Heidegger’s Topology: Being, Place, World MIT Press

Pope, Alexander, 1731 Epistles to Various Persons: Epistle IV Of the Use of Riches, to Richard Boyle, Earl of Burlington.

Ruskin, John, 1846, Modern Painters Vol II Section II, Chapters 1-IV

Sheers, Owen 2008 “Poetry and Place: some personal reflections” Geography, Vol 93 _Part 3 2008 accessed at http://www.owensheers.co.uk/pdf/geography.pdf

Windfall: A Journal of Poetry of Place accessed at http://www.hevanet.com/windfall/poetryofplace.html

Wordsworth, William, 1798 “Lines composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey” in D.C. Somervell (ed) 1920 Selections from Wordsworth, J.M. Dent and Sons.

Wright, C.D. in Jeremy Richards, ”A shifting Sense of Place: four poets discuss where their work belongs in the world,” accessed at https://www.poetryfoundation.org/articles/69640/a-shifting-sense-of-place