This post summarises two considerations that are I think are essential for an attempt to forecast the future of places over the next thirty or more years,

• Continuity, or the aspects of places that persist in spite of change

• The triggers that have frequently played a role in causing changes in how places have been made

Continuity in Places

The identities of places are the product of both continuity and of change. Some aspects of their identities tend to persist, enduring for centuries or even millennia. Other aspects, the ones that comprise much of the character of places, are the result of adaptation to and accommodation of changes.

Persistence: The names of particular locations, unless they are forcibly removed by conquest and colonisation, can stick for centuries, even millennia. The same can be said of roads and street patterns, Once created, these are unlikely to be changed in any substantial way, presumably because they are public rights-of-way that are needed for places to function. Some institutions – the Catholic and other Churches, universities – have found ways to survive repeated political and economic turmoil. And it is striking that the even though the hey-day of religious placemaking was in the Middle Age, not only have cathedrals built then survived to the present, but new ones, for instance in Liverpool and Barcelona, were still being built in the 20th century. The first universities were also a product of the Middle Ages, and university campuses have multiplied and are still expanding.

Another form of place persistence happens when towns or villages were by-passed by progress yet were sufficiently resilient to survive in spite of that. The result is landscapes and townscapes left mostly untouched by changes happening elsewhere, where local architectural styles and other placemaking practices continued to be used. (Now, of course, places like this are deliberately preserved for their picturesque heritage qualities and new buildings are required to be in complementary designs).

Vernazza in the Cinque Terre in Italy, and Weobley in Herefordshire, England. Two places demonstrating persistence of identity – each with a distinctive styles of vernacular architecture that has been used over several centuries. In Weobley the oldest black and white buildings in the middle distance date from the 15th century and those in the foreground from the 19th century.

Adaptive Continuity: The second form of continuity in places happens through the accommodation of shifts in ways of building or social and economic circumstances by adding to or modifying whatever already exists. The consequence is that, although there may have been a radical change in ways of making and experiencing places, the personality of a particular place has continuity because it has been altered incrementally around a core identity that involves names and older buildings. Elements from different eras are interspersed and juxtaposed, and the resulting townscape expresses what might be called adaptive continuity.

Of course, villages and small towns have sometimes been abandoned because they are economically obsolete, or effectively disappeared because they have been swallowed by urban development. Nevertheless, most large towns and cities that were founded more than about a century ago are likely to show evidence of adaptive continuity to meet changing circumstances. The overwhelming evidence is that place want to survive and that the largest ones also want to continue growing. For places on the scale of Uruk or Tikal to be abandoned in takes the collapse of entire civilization.

The Mayan city of Tikal in Guatemala was a major centre for a millennium. At its peak about 800 CE it may have had a population of 90,000 , but was abandoned in the 10th century as Mayan civilization collapsed, probably for a combination of political and environmental reasons.

Triggers for Change in Places

As I have indicated in previous posts (here and here) the history of places also shows that, for all their continuity, there have been several fundamental changes in how places have been made and experienced over the last 2500 years. Each of these changes was the result of a radical shift that involved some combination of, I think, four major processes

• technological innovations

• new ways of thinking about the world and the role of humans in it

• the emergence of political and social structures that allowed those new technologies and ways of thinking to be turned into practices

• underlying all of these, population and urban growth drive the need for more and larger places.

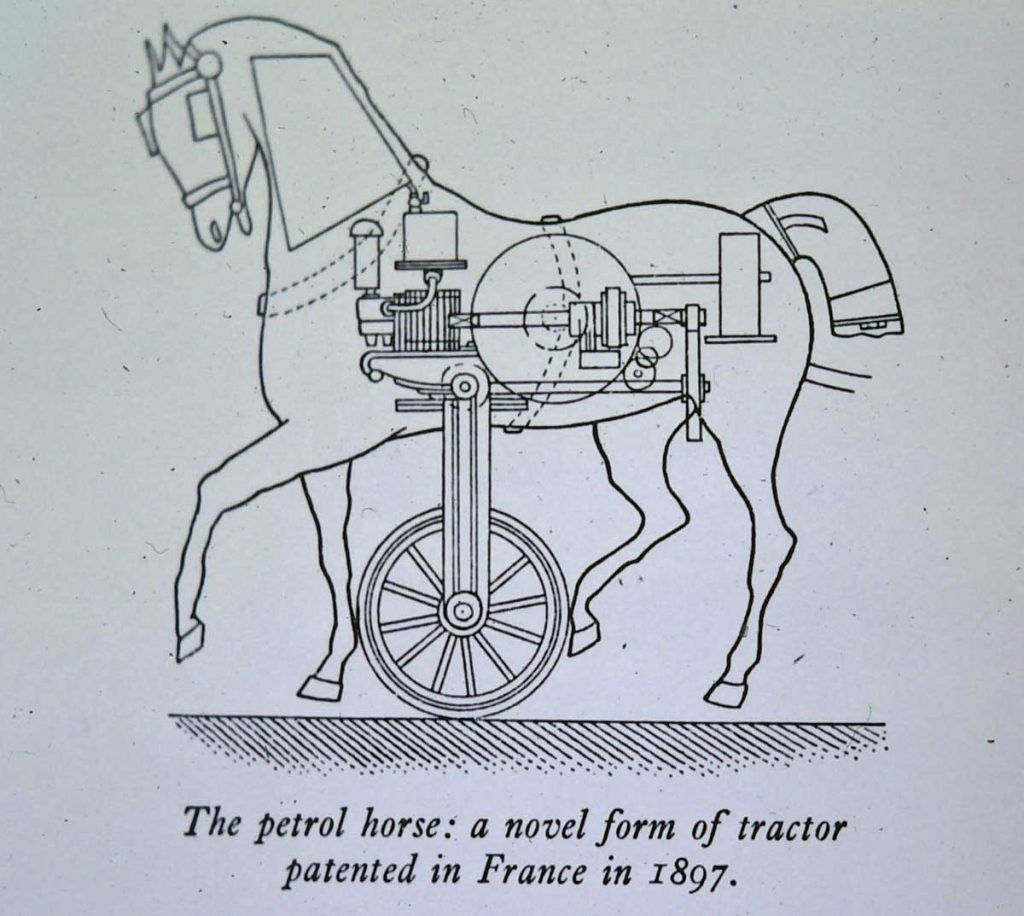

Technological Innovations: The invention of new technologies – especially media of communication (roads, printing, railways, telegraph and telephone, highways and motor vehicles) – modified relationships between places by speeding up how knowledge and practices were transferred between them. In addition, other innovations (columns, domes, pointed arches, domes, steam power, materials such as concrete and steel frames for skyscrapers) introduced new types of building that made possible new ways of making places. In hindsight, these technologically induced changes seem to be clear, but at the time their consequences can be far from obvious and are easily misinterpreted.

Ideas and Systems of Belief: The emergence of new world views or religious beliefs played a role in the emergence of every new period of places – Roman imperialism and pragmatism overwhelmed Classical Greece; Christianity provided an organisational foundation for societies to emerge from the Dark Ages; the Age of Reason drew inspiration from the Classical Period relegated religion to a secondary role and remade landscapes along geometric lines; the refinement of economic thought by Adam Smith was a foundation for the industrial capitalism in the Industrial Era that converted reason into utilitarianism for the benefit of profit; Modernism rejected historical revivals and turned capitalism towards efficiency and an international view of the future in which the distinctiveness of places was almost irrelevant.

Political and Social Values: Changes in belief systems were usually connected with shifts in political values and power. The Romans developed practices of government and administration that made possible the expansion of the Empire; failure of that system of government and the security it provided resulted in the disorder of the Dark Ages. The administration of the Catholic Church, which was the foundation for making places at the beginning of the Middle Ages, was weakened as popes and cardinals became increasingly absorbed with their own power and wealth. Authority passed to kings and princes, but in due course, they too became self-aggrandizing and detached from the people they ruled, and monarchies were overthrown in various revolutions that established versions of liberal democracies that have prevailed since the early 19th century.

In general, it seems that whenever social and economic inequality has intensified it has contributed to enduring shifts in political systems, and that these have been associated with new ways of making and experiencing places.

Growth: Population and urban growth underlie the entire history of places (as I indicated here). It is, however, not clear in what ways these have been triggers for particular changes except as ongoing background demands that have had to be resolved by making more places, for instance by creating colonies or new towns, and by making existing places larger. In these respects the very rapid population and urban growth since 1800 has had a profound impact on how places have been made. This impact has been especially pronounced since about 1970 as global population doubled and cities almost everywhere have grew both upwards and outwards at unprecedented rates and scales.

Implications for the Future of Places

The message of persistence and adaptive continuity for the future of places is clear. Notwithstanding some massive disaster, many aspects of places as they are now will continue to exist for decades and possibly centuries. Furthermore, because the world’s population has doubled from 1970 to 2020 (from 3.7 billion to 7.5 billion), and the majority of that growth has been accommodated in urban areas (from 1.4 billion to 4.3 billion), most of the current built environment and its places are products of the last half century. There will, of course, be modifications and adaptations to these as new technologies are developed, and new ideas and social systems emerge, but in some form the places made over the last half century will be a huge part of the places of the foreseeable future.

In order to contemplate the future of places, the almost certain fact of this continuity has to balanced against indications that the various triggers for change – technological innovations, systems of belief, social and political values – could be intensifying. In my next post I will examine trends hat have emerged in the last half century which are affecting ways that places are made and experienced, and are likely to continue to do so in the immediate future.