[Prefatory Comment: Ah, the power of the Internet. The map of The Country of Islandia in this post was reprinted in the online version of The New Yorker November 2, 2016, to accompany an article about Islandia. It was also reprinted in Laura Miller (Ed), Literary Wonderlands: A Journey through the Greatest Fictional Worlds Ever Created, Black Dog and Leventhal, New York, 2016.]

Islandia by Austin Tappan Wright is a utopian novel originally written in the years around 1910, and first published in 1942 that is remarkable both because love of place is a central theme and because the author was the brother of John Kirtland Wright, a well-remembered humanistic geographer who was librarian and subsequently director of the American Geographical Society.

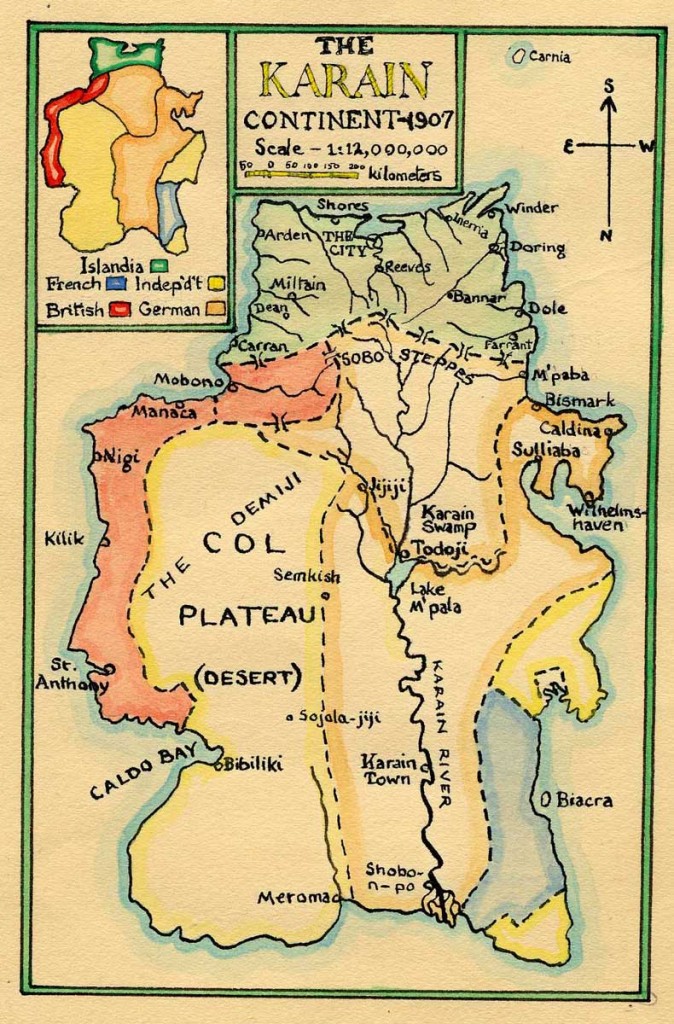

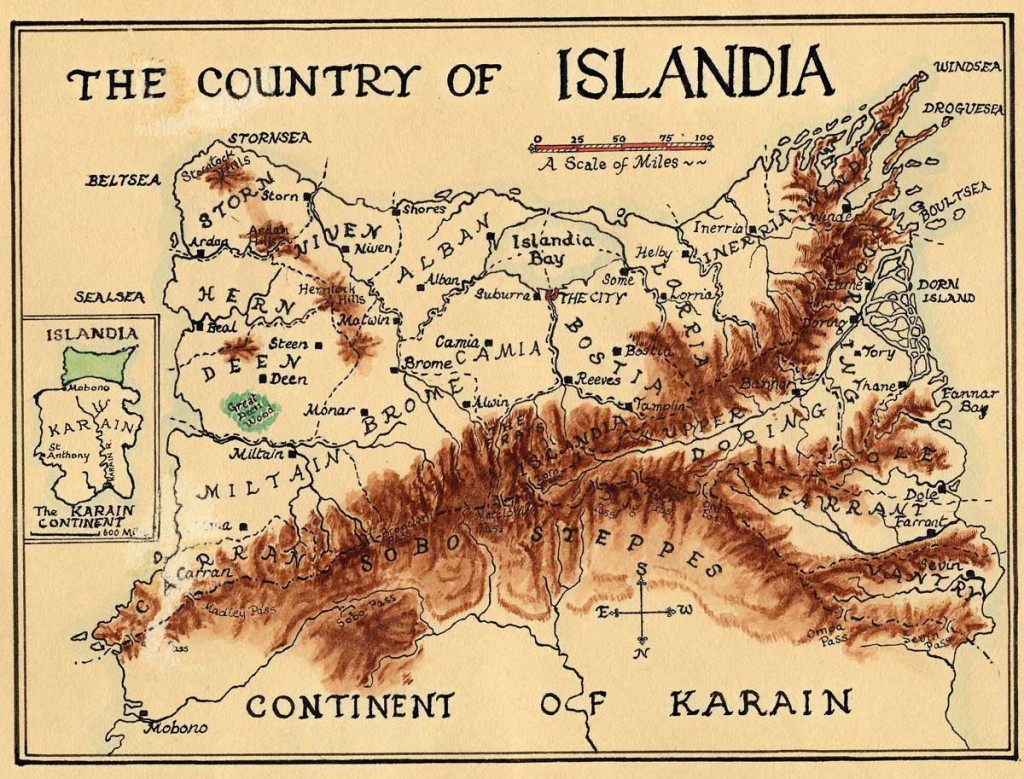

The novel is about a nation called Islandia on the imaginary Karain subcontinent somewhere in the southern hemisphere where connection with place is a driving impulse and where almost all forms of technology (which effectively means machines) that might threaten that impulse are rejected. It was written not for publication but as a labor of imaginative creation. Austin Wright, who was a law professor, also wrote a history, a glossary of the language, and a description of the country, all of which are unpublished. The novel was published posthumously in 1942 by his wife (who edited it down from 2000 pages) and daughter, and includes several maps drawn by his geographical brother. These are very murky black and white, and at some time in the 1970s shortly after I read Islandia for the first time, I redrew two of them for my own amusement and these are reproduced here. They are accurate reproductions of the originals except for the addition of color.

The geopolitical context of the novel now seems very dated – with three European colonizing powers occupying the northern part of the Karain continent (the maps were oriented in the antipodean manner, with south at the top), which is sub-tropical and occupied by black and brown peoples. Islandia is a white, temperate and isolationist nation in the southernmost part of the continent, and is separated by a range of mountains. The context of the novel is that the English, French and Germans are competing to get a potential shares of the resource wealth of Islandia, where there is political turmoil about whether to end isolationism and to allow machinery to replace traditional ways of doing things. The central character is John Lang, the first American consul to Islandia. Initially, after his experiences in the big cities of Boston and New York, he cannot understand the backward, agrarian character of the country, where everything moves slowly, travel is on foot or horse or sailboat, and work is mostly done by hand. But over the course of several years, he comes to appreciate this way of life, sides with the traditionalists, fights with Islandians against potential European colonial initiatives, and, because he was instrumental in preserving Islandian isolation, is one of few outsiders allowed to settle there.

From the perspective of place there are several remarkable aspects of Islandia. The imagined landscapes of farms, mountains, marshlands, buildings, settlements, and The City (the only large urban area – on Islandia Bay) are described in vivid detail. I have always thought that Wright drew on some aspects of New England geography and its landscapes for his inspiration, but have no firm basis for that. Islandians are presented as having a deep compatibility with nature, the sort of compatibility that Wes Jackson and those who advocate life in harmony with ecological processes would advocate, and which gives them great resilience. In its rejection of machine technologies the novel has something in common with Samuel Butler’s Erewhon (also set in the southern hemisphere) and William Morris’ News from Nowhere, although there is no reference to these.

In its powerful emphasis on sense and love of place, however, Islandia is unique. In the language of Islandia there is a special word for love of place – alia (amia means love of friends, apia means sexual attraction, and ania means desire for marriage and commitment). Islandian individuals and families are strongly connected to the places where they live – they know the weather, landscapes, plants, customs and people – and they appreciate that other Islandians living in different places have a similar love for their places. Furthermore they understand that alia passes from one generation to the next, so caring for one’s place is an intergenerational responsibility. It is, in short, a quintessential account of a pre-modern, pre-industrial sense of place.

Alia is implicit throughout Islandia, elaborated mostly through specific accounts of its places, people and landscapes. It is discussed infrequently and briefly as a concept, in part because to Islandians it is so utterly self-evident that it requires no explanation. Here, however, are three extracts that deal explicitly with love of place (Dorna is an Islandian woman with whom John Lang falls in love):

779 “Alia means one’s love for one’s home place and family as a going thing.”

223 On a comparison between Americans and Islandians: “The point that Dorna made …was that we were “unplaced,” we wandered about alone in the world as homeless as fish in the sea; whereas the Islandians really had a place from which they came and where they were buried at death.”

471 In a speech made by Dorna at the National Council arguing for the continuation of Islandian isolationism: “Our whole way of life is based upon these centers – upon family and place as one. The roots of our being grow in the soil of our alia. Family and place intermingled as one make that soil.”

I have no idea now how I first encountered Islandia. It was out of print for many years, and does not seem to have a wide readership. There are a handful of comments on the web about it, mostly favorable, but also indicating that people either love or hate it. Aspects of it are very dated, the white Islandians versus the black and brown people to the north conveys racial superiority, parts of the story are simplistic. On the other hand, the case for an agrarian, place-based way of life rather than an unplaced machine-based way of life is presented in terms of the numerous misgivings that have to be overcome by the hero. Finally, it has to be remembered that this never was intended to be a novel. It was Wright’s personal imaginative account of a utopian society grounded in place that became a novel in which place is a central character.

Wright, Austin Tappan, 1942 Islandia, (New York: New American Library) (1958 Edition)