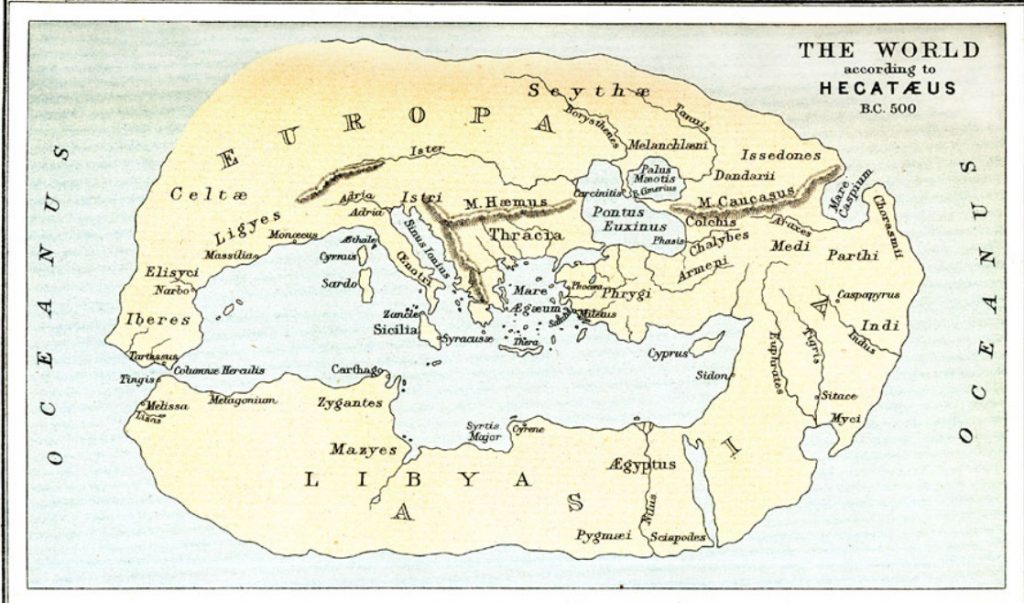

Hecataeus of Miletus published a map of the world about 500 BCE, and Eratosthenes of Cyrene is the person credited with creating the word “geography” about 225 BCE. In ancient Greece individuals were named for and identified by the place they had been born. More than two millennia later the novelist Lawrence Durrell (1969) claimed that: “as long as people keep getting born Greek or Italian or French their culture productions will bear the unmistakable signature of the place.”

Whether you agree with Durrell or not, it always seems to have been accepted that people’s personal and social identities somehow reflect the identities of the places they come from or live in. In this post I consider what is meant by identity of and with place and how these meanings have recently begun to get increasingly varied.

Three Aspects of Identity

A “law of identity” in logic holds that everything is identical with itself. This may not seem very helpful, but it lies at the root of the legal assumption that identity is what makes each of us distinct from everyone else, something confirmed when we are required to provide proof of our identity. Similarly, the identity of a place is what makes somewhere different from everywhere else.

The notion of identity in mathematics takes this a step further because it refers to instances where apparently different things can be shown to be identical (as in proofs in algebra). While this sort of strict equivalence does not translate well to what happens in everyday life, it suggests that aspects of individual identities can be shared. In psychiatry personal identity is said to involve both a persistent sameness within oneself and a persistent sharing of some characteristics with others. Similarly, characteristics of the identity of place are shared between different places.

There is also a social form of place identity – the identity of persons with places. Both individually and as groups, we identify in some way with places, for instance where we were born (essential for proof of personal identity), or the region or city where grew up or now live.

Identity of A Place

The identity of a place consists of the unique combination of intrinsic characteristics that make it distinctive. This apparently straightforward definition is in fact elusive because “a place” can refer to anywhere from a room to a region to a nation. Fortunately it is easier to get a handle on identity because regardless of the size of place it is made up of three interrelated components that cannot be reduced to one another.

• Forms consist of topography, buildings, spaces and things. They are whatever would remain if people and all their activities were removed.

• Activities, or what goes on somewhere, including processes of ecological and other changes, land uses, and movements of traffic and people. Some of these can be observed and measured objectively.

• Meanings. Aesthetic, spiritual, political, cultural and ethical values associated with places, including memories, histories, traditions, symbols and plans for the future. These may be revealed in and reinforced by certain built forms and activities, perhaps most obviously in heritage, but are difficult to deduce from them. You have to know about the values people attach to places in order to see evidence of them.

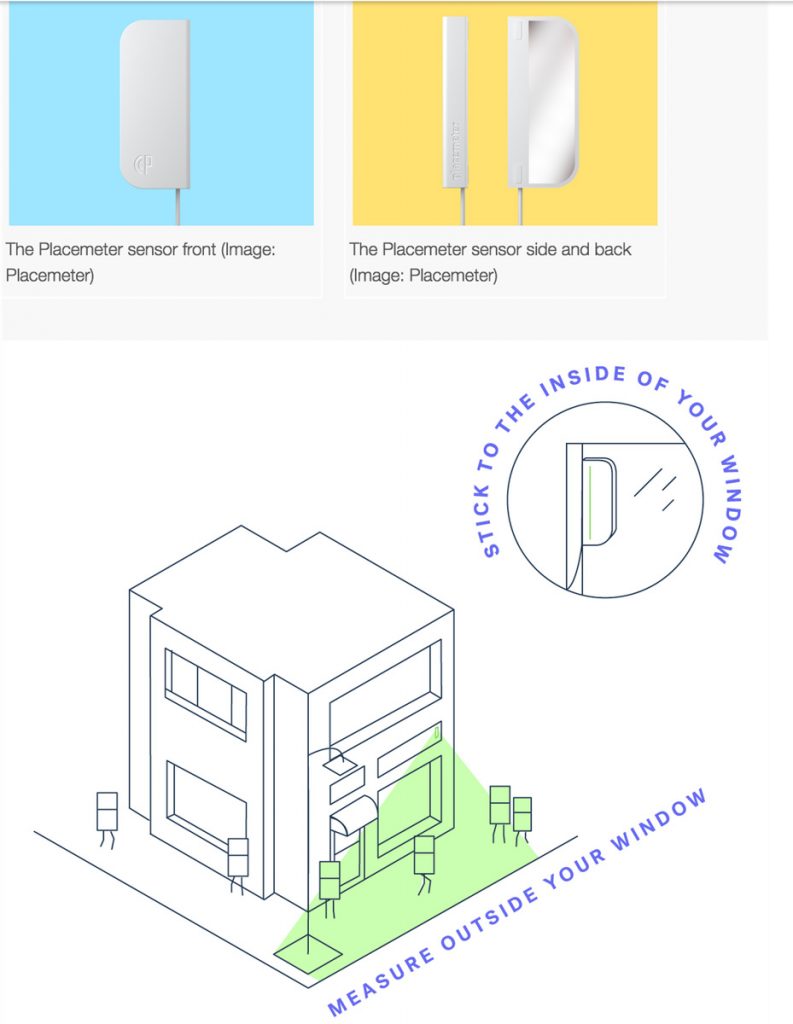

Three places that respectively stress forms, activities and meanings in their identities. The chapel at IIT in Chicago, designed by Mies van der Rohe. A system for measuring pedestrian flows outside stores devised by the survey firm Placemeter (see References at the end of this post). The grave of John McRae, who wrote the remembrance poem In Flanders Fields, in a WW1 cemetery near Ypres.

The identity of every place, no matter what size and no matter how bland or spectacular it seems, is comprised of these components. The relative weight of them varies. In some cases spectacular forms are dominant, others (for instance sports stadiums) may be little more than empty spaces until filled by events, and some otherwise innocuous places (for instance, military cemeteries) are filled with meaning though their forms are minimal and they have almost no activities.

The identities of places change over time as buildings are added, trees grow, new technologies are introduced, fashions shift, and events happen that are incorporated into place memories and meanings. These changes are mostly incremental so that place identity, somewhat like personal identity, has continuity and persistent sameness. In addition, aspects of the components of place identity, such as landforms, architectural styles, types of land use, festivals, and religious beliefs are widely shared, so that different places have enough in common to make them more or less comprehensible even if their environments and cultures are unfamiliar.

Identity with Place

The identities of places can be considered quite dispassionately, especially if the focus is on forms and activities, for example, in planning reports. In contrast, identity with place involves emotions and feelings. The composer Frédéric Chopin identified deeply with his homeland of Poland. He left in the 1830s because of political upheavals there and never returned, but always carried a jar of Polish soil with him. When he was buried in Paris, his heart was, in accordance with his wishes, taken to Warsaw for burial.

This park in Salt Lake City suggests several layers of identity with place. It is on the site where Brigham Young, who had led the Mormons across America in search of somewhere they would “make the desert blossom like a rose,” looked out his wagon and declared “This is the right place.”

Such intense identity with place may be rare, but where we come from is a basic fact of existence that enters in our personality. For some it may be little more than a line in a passport, but for others it is essential to self-identity, reinforced by memories of landscapes and events, accents, attitudes, and beliefs that comprise an individual’s geographical past. Elena Liotta, a psychoanalyst, writes in her book Soul and Earth” (2009): “A place takes on meaning as a result of the sensations and emotions elicited and the consequent attachments formed…External space becomes interior space, a subjective space and time of experience, memory and emotions” (p.6). And…“If one knows how to look the beginnings hold everything” (p.41). In other words, where we come from echoes through our subconscious.

Shifting Attachment to Place

Identity with place overlaps with the idea of what environmental psychologists and others have called “place attachment” (see Lewicka 2011, Manzo and Devine-Wright 2014, Seamon 2014). Their research demonstrates that for an individual place attachment is rarely static. It changes character as circumstances and intentions change, emerging out of involvement in typical daily goings on somewhere, and growing into becoming a member of a community in a place.

There is always a tension between mobility and place attachment, between roaming and putting down roots. Over a lifetime these processes of forming attachments to a place may be repeated several times in various locations. This is the case for migrants who form identities with very different places that are separated by oceans and continents. For groups of migrants this process of identifying with a new place often involves changing the identities of a place by grafting names, temples, stores and restaurants, and culturally specific activities onto the forms and landscapes of the places they have moved to.

Decline of the Born and Bred Narrative of Identity with Place

The tension between mobility and attachment has been clarified by Stephanie Taylor’s research (2010) into the relationship between women’s identities and place in contemporary societies. This brings into question what she refers to as the “born and bred cliché” that home town, home country, or native land “produces a sense of belonging and sense of identity as a person of that place” (p.22). This link has been weakened by increased mobility and changes in the character of place attachment

Place, she argues, is shifting from its former meaning as a geographical context to a community constructed through choice. Place now is as much chosen as it inherited. Retirement communities in locations with pleasant climates, the choice of place to go to university, and gay villages are indications of this. Taylor suggests that for the women she studied identity with place has evolved to become an open-ended process, partly personal and partly related to changing social contexts. A place, she suggests, is chosen because it matches who a woman want to be.

Gay Village Toronto, 2002

Advertisement on a bus for Otago University, 2014

Diversification of Identity and Place

That identity with place is shifting away from the born and bred narrative is reinforced by an annotated bibliography prepared by Marco Antonsich (2014). This focuses on work by geographers, but also includes contributions by philosophers, psychologists and others. It demonstrates the increasingly wide range of recent research on identity and place, which he puts into three broad categories.

• Phenomenological accounts by humanistic geographers and the empirical research of environmental psychologist into place attachment that stress aspects of belonging to a physical environment such as a home or neighbourhood. In various ways these tend to contribute to the born and bred narrative.

• Geographies of difference associated with gender, sexuality, race and class that raise issues about inclusion and exclusion in place identity. This research emphasizes the roles of society and politics rather than a geographical setting in place experiences, and that for some groups these can mean identity with place can be a negative rather than a positive experience. For refugees and migrant workers living in camps, prisoners, the homeless or poorly housed, women experiencing violence at home identity with place involves unpleasant necessity, drudgery, disconnection, tension rather than belonging.

• Investigations of globalization explore how processes of global economic flows transnationalism and cosmopolitanism challenge the role of geographical contiguity in place identity because they involve attachments and relationships to several different places. For migrants these can be profoundly different, both environmentally and culturally. However, electronic communications, international travel and social media have facilitated identity with many places, eased the intensity of differences, and made choice of places increasingly possible, not for everyone but for many.

On the left, “A place where people want to be” is Mississauga, a city adjacent to Toronto. “Vote Green because we love this place” was an election poster in British Columbia, 2018.

Comment

It’s obvious that the identities of actual places, both large and small, have undergone huge changes in the last half century. Skyscrapers, suburbs, big box stores, tourist resorts, container ports, deforestation, homeless camps, deindustrialization, gentrification, industrial scale agriculture, mass migration from less to more developed countries, international airports. These may have change the identities of places. They have not undermined the logic of place identity. The basic components of forms, activities and meanings still apply, and sharing aspects between places has simply intensified with increased international travel and communication.

It is less obvious how changes in the identities of places have affected and been affected by shifts in how people identify with places. Inherited, born and bred identities with places, which prevailed for much of history, have recently given ground to attachments with many places, either because of migration or through options to work in or travel to different parts of the world. Over the course of one or two generation, identity with place has for many people become a matter of choice rather than necessity.

Lockdowns and travel restrictions because of the Covid-19 pandemic have halted this trend. The identities of places have changed little, but our relationship to the places where we live has been abruptly brought in sharp focus as the choice to move elsewhere has been dramatically reduced. My sense is that responses to this are mixed. There is support for whatever is local – businesses, outdoor recreation, volunteering for those in need, street performances by musicians. But there is also a frustration with, in effect, being confined to a place and with lost opportunities to travel. As the pandemic subsides the outcome seems likely to be a surge of enthusiasm for travel to other places, a return to trends previously underway to form identities with many places and to choose places with communities of like-minded people. My hope is that these trends might be tempered by an enhanced identity with the places we live in them because we have learned out of necessity to appreciate their value.

Antonsich. M., Identity and Place, 2013 in B. Warf (ed.) Oxford Bibliographies in Geography, New York: Oxford University Press, available online here.

Durrell, Lawrence, 1969 Spirit of Place: Letters and Essays on Travel, London: Faber and Faber.

Lewicka M,. 2011 “Place Attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years?” Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), 207-230

Liotta, Elena. 2009 On Soul and Earth: The psychic value of place. London: Routledge.

Manzo, Lynne and Devine-Wright, Patrick (eds), 2014 Place Attachment: Advances in theory, Methods and Applications, New York: Routledge.

Placemeter was a company that from 2013 developed “computer vision and machine learning algorithms to transform video streams from public cameras into data about the volume and direction of pedestrians, bicycles, bikes, and vehicles.” I believe it was acquired by Netgear in 2016.

Seamon, David, 2014 “Place Attachment and Phenomenology: The Synergistic Dynamism of Place” in Manzo, L. and Devine-Wright, P (eds) Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications, New York: Routledge

Taylor, Stephanie, 2010 Narratives of identity and place, London: Routledge,