Introduction

There have been four major events or episodes in the last eighty years that have had worldwide effects with lasting consequences for places. These are the invention and deployment of nuclear weapons, explosive population growth, anthropogenic climate change, and almost universal engagement with electronic media. I don’t consider other important events, such as the mass production and distribution of antibiotics, decolonization, the discovery of DNA and genetic modification, computing, satellites and space exploration, and the shift towards gender equality, because their consequences for places are arguably more limited. The four I have identified stand out as exceptional because, like plate tectonics, they are manifestations of fundamental processes of change that move quite slowly and in the background, yet have affected and are continuing to affect places in substantial ways on a worldwide scale.

By ‘places’ I mean here the geographical parts of the public world that are encountered in everyday life and with which people often have some emotional attachment – neighbourhoods, towns or cities, and regions. Although these consist of many juxtaposed and intertwined things – buildings, roads, traffic, trees, people, landscapes, memories and so on – we experience them as whole environments that are familiar, usually taken for granted, and can be simply identified by their names which serve as metaphors for their complex whole identities.

Places, it has been suggested, are openings to the world because they are first of all things; our experience of whole places necessarily precedes the elaboration of scientific theories or ideologies. They are manifestations of what the political philosopher Hannah Arendt called “The common-sense world which neither the scientist nor the philosopher ever eludes.” (1978, p 26). But places are also open to world. Nowhere is an island, everywhere is affected by processes and events that originate elsewhere and which function at a large scale – trade, fashions, ideologies, technological innovations, plagues, imperial domination.

This essay is about the way places and experiences of place appear to have been profoundly affected by four transformative events that have originated since the end of the Second World War, and whose consequences will continue to be felt long into the future.

1. The Background Threat of Place Annihilation

Since the 1945 bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki places everywhere have existed in the shadow of possible destruction by nuclear weapons. Hannah Arendt considered this to be one of two destructive turns in the modern age (the other was totalitarianism), and a turning point in all human existence because humanity had for the first time acquired the power to destroy itself. Worries about about a possible apocalypse from some speculative cause have probably always existed, but now the world faces the known risk of self-inflicted, worldwide, mutually assured place annihilation.

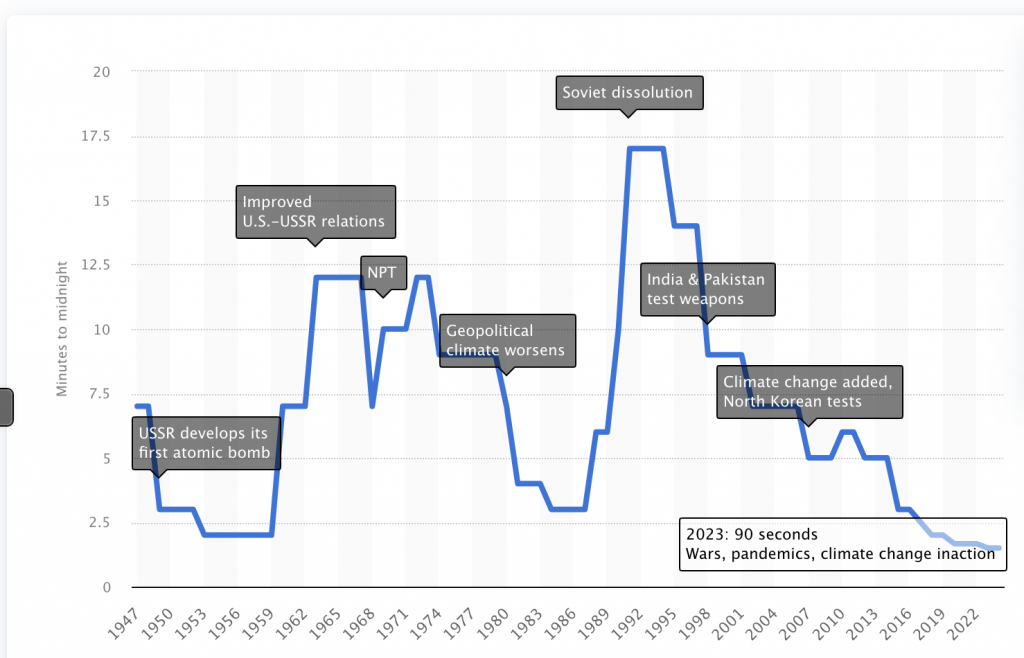

This has had remarkably little impact on places and placemaking. Since 1945 populations have grown, cities have expanded, greenhouse gas emissions have increased, life expectancies have become longer. Nevertheless the missiles and nuclear arsenals are real, and the risk of their use is the omnipresent background to place experiences everywhere; it would take little more than an impetuous decision by an upset political leader for the worst to happen. The Doomsday Clock, introduced by atomic scientists in 1947 to suggest how close the world is to the midnight of nuclear catastrophe, and which now also includes risks of extinction posed by biotechnology, climate change and AI, is currently set at 89 seconds, the closest it has ever been.

A Place Corollary: The United Nations

The United Nations was founded in 1945, in the wake of the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, to achieve international co-operation and prevent future world wars. The UN is notable as the first institution that treats the Earth as a single place consisting of the many smaller places of its member countries. Since 1950 it has systematically gathered and provided data about global and national issues affecting places, such as population and the size of cities (which I have used in this post). The UN promotes global and local sustainability, including the preservation of specific places that are considered to have global significance, such as World Heritage Sites. It therefore signals an important shift in sense of place away from a focus on what is mostly local to interactions between local experiences and global processes.

2. Population Growth, Urbanization, Population Decline

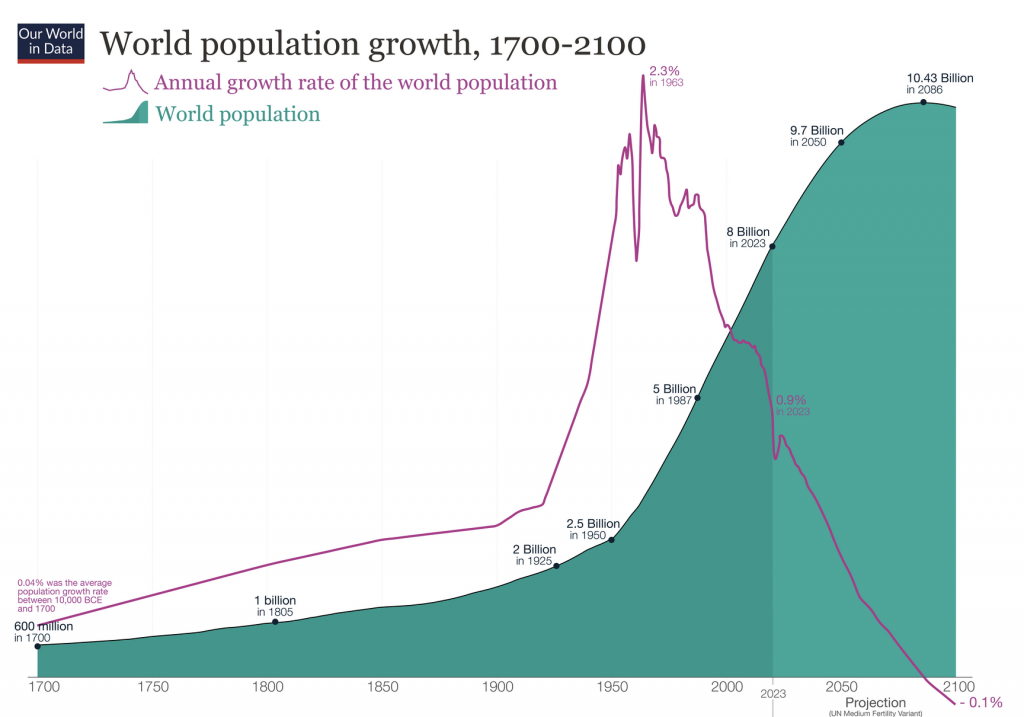

It is impossible to overstate just how exceptional global population changes since 1945 have been. It took about 10,000 years for the world’s population to grow from probably less than 4 million at the end of the last Ice Age, to about 2.3 billion people in 1940. Since then growth has been about a billion people every twelve years, a total of almost 6 billion in seventy years. Nothing remotely like this has happened before. And it will not happen again, because paradoxically, in the midst of this growth fertility rates have dropped below replacement levels in all developed countries, including China and India, so that before the end of this century populations everywhere are going to age rapidly and then for the first time ever slide into absolute decline.

(Source: Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/population-growth-over-time)

A few decades ago there were predictions of catastrophic outcomes from overpopulation. That didn’t happen because somehow resources did not run out and economic development kept pace. Nevertheless, the sudden addition of almost six billion people has had a huge impact. In 1950 there were 2.5 billion people occupying the lived-in places in the world. In 2025 there are 8.2 billion. That’s an additional 5.7 billion (70 percent of global population) who live in newly created places of some sort – high-rise apartments, new cities, suburbs. Somewhere between one and two billion new dwellings (the number depends on average household size) have had to be constructed. Building, maintaining and servicing all these these has required quadrupling supplies of resources, products, food and energy, which has in turn required the widespread construction of new non-places with no resident population and no history, such as oil fields, power plants, manufacturing facilities, container ports, shopping malls, and international airports. In short, at least three quarters of all the places where people currently live, and most of the non-places supporting them, have been created since 1950 (about half have been made since 1975)..

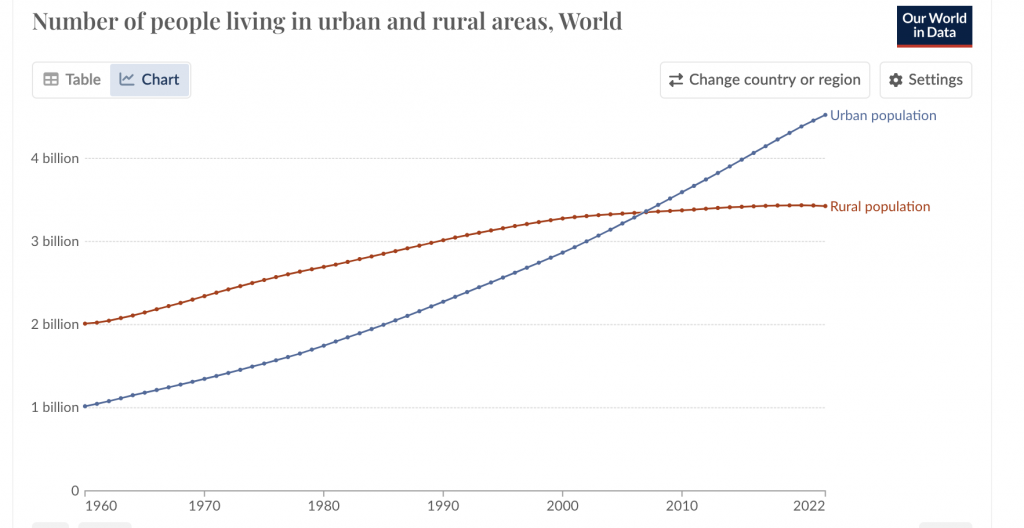

The clearest effect of this surge of population growth has been to turn the world urban. Four billion of the additional 5.7 billion people have been accommodated in cities and towns. When the UN made its first systematic estimate in 1950, 29.6 percent of the world’s population was urban. Around 2006 for the first time in human history more than half the world’s population was living in cities. The percentage is now 56 percent, and is expected to keep climbing, even where populations are declining, to the 80 percent levels of developed countries.

(Source: Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org/urbanization)

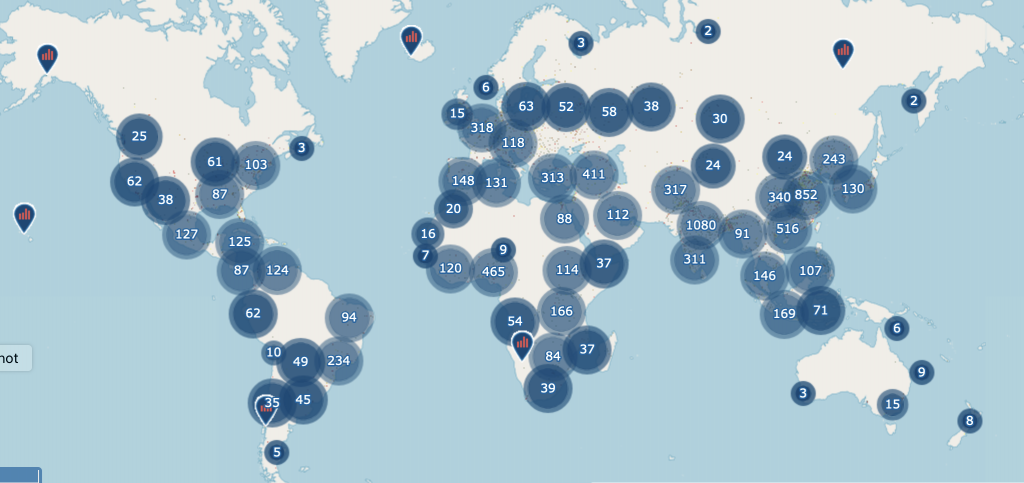

The effect of urbanization has been that cities around the world have metastasized into denser and ever larger megalopolitan regions that can be a hundred or more kilometres across with several centres linked by quasi-urban corridors of suburbs, industrial subdivisions, discount malls and distribution centres. In 1950 there were two megacities with populations of more than 10 million and another 74 cities with more than a million people. There are now 44 megacities and over 600 cities with a million or more. Together these house a quarter of the world’s population.

What all this growth means is that while place in 1950 could be reasonably be understood in terms of rural settlements and small towns or cities that had communities of neighbours sharing a local sense of place, it now has to be understood as primarily an urban phenomenon involving strangers living in high density, artificial environments which take hours to drive across, comprised mostly of buildings in the placeless styles of modernist architecture, where communities are based as much on shared interests as proximity.

(Source: https://human-settlement.emergency.copernicus.eu/ucdb2018visual.php#)

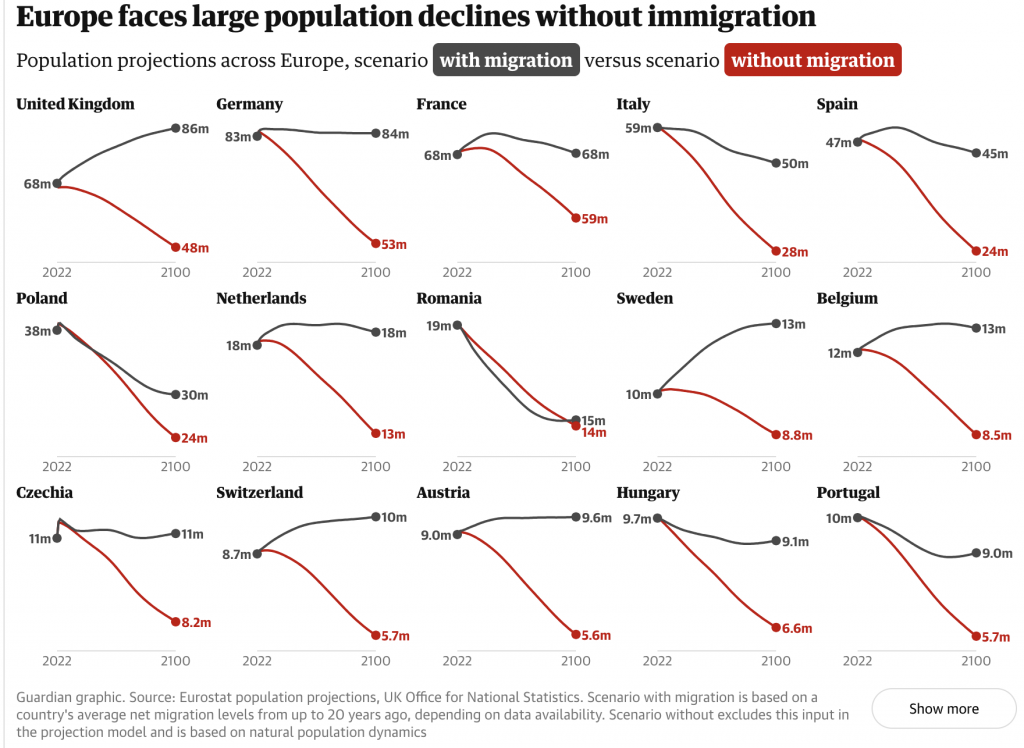

The place consequences of population decline are more subtle than the huge scale of placemaking associated with growth, in part because they have been disguised by immigrations, and in part because they are just beginning to become apparent. The global fertility rate (number of live births per woman) peaked at 5.2 children in the 1960s then began to fall everywhere, and now only in sub-Saharan Africa and a few Middle Eastern countries are populations growing. In North America, and many European countries, where fertility had fallen below replacement by the early 1970s, national populations would already have declined if they had not been bolstered by immigration from less developed parts of the world. This immigration has transformed the identity of many places, especially urban ones, from the cultural homogeneity that previously prevailed to cultural and ethnic diversity.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2025/feb/18/europes-population-crisis-see-how-your-country-compares-visualised)

Where immigration has not compensated for a falling population, for instance Japan, the evidence of population decline is already visible in abandoned houses and depopulated small towns. This will be the future wherever fertility rates fall below replacement, including China, where current UN population projections suggest that by 2100 the population could have shrunk by as much as 800 million. A decline of even of few million in a nation’s population will pose significant problems initially as populations age, and for places at all scales there will be significant issues and then as former priorities about placemaking to accommodate more people will have to shift towards finding ways to shrink cities and abandon existing communities.

3. Climate Change

In 1981 atmospheric physicists at NASA (most notably James Hansen. who a few years later made a presentation about climate change to a Senate committee that triggered widespread awareness) published a paper in the journal Science on the “Climate Impact of Increasing Carbon Dioxide” (Hansen et al, 1981).This identified a clear correlation between human sources of rising levels of CO2 in the atmosphere and increasing temperatures and projected that, depending on the rate of economic growth, global average temperatures would rise between 2.5°C and 4.5°C by 2100. Its conclusion was that this is something “of almost unprecedented magnitude” in both geological and human history, “not seen since the age of dinosaurs.”

This conclusion has been reinforced by numerous subsequent studies, and evidence of it has become apparent in steadily rising mean global temperatures and intensifying extreme weather. In spite of numerous promises, policies and initiatives to reduce emission, concentrations of CO2 in the atmosphere have steadily gone up since the 1980s and are now higher than at any time in the last 16 million years.

While climate change is mostly described at a large scale – global mean temperature and so on – the fact is that greenhouse gas emissions come from specific places, and it is in specific but mostly different places that the damage caused by increasing extreme weather happens. National and international strategies to mitigate emissions and encourage adaptations are essential, but these have to implemented in ways that are tailored to local circumstances – rising sea levels for coastal locations, wildfires where there are forests near cities, melting permafrost in the Arctic, severe floods almost anywhere near a river. In cases where individual places are especially vulnerable to extreme weather events, the only feasible adaptation is a strategy euphemistically called “planned retreat”, in other words abandonment and relocation of communities.

We are at the relatively early stage of anthropogenic climate change. The stark choice presented by the climate crisis is either to make transformative changes now to the ways everyday life is lived in places – to eliminate fossil fuel use, cut use of plastics, reduce travel, modify diets, buy local – in an attempt to reduce emissions and stave off the worst consequences from a climate not experienced in millions of years. Or to continue life pretty much as usual and so ensure that over the next century buildings and infrastructure in most cities will have to be rebuilt to accommodate the realities of unprecedented extreme weather, and in all probability many places both urban and rural will have to be abandoned because they will have become unliveable.

4. Electronic Media and Sense of Place

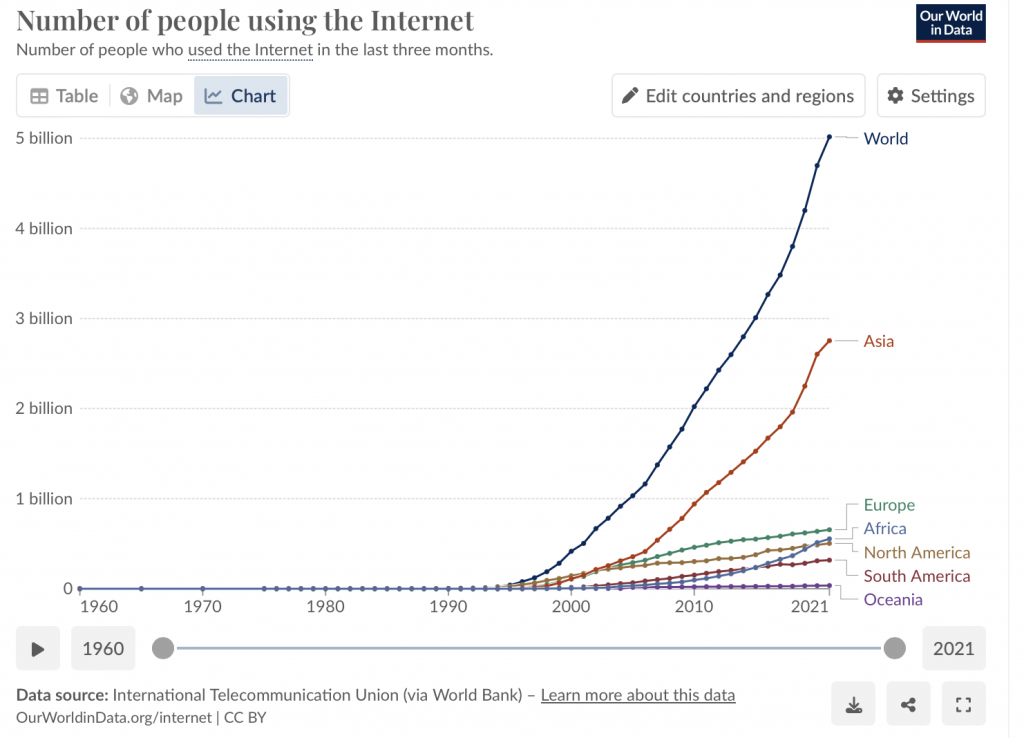

The impacts of electronic media on place, and specifically sense of place, are more speculative than those of demographic and climate change. The reason I think they are important is implicit in the fact that since 1994 internet use has gone from a miniscule 0.01percent of the global population, perhaps 500,000 academics and computer scientists, to 68 percent, or 5.6 billion people, and it is continuing to grow at about 560,000 every day. There are currently 5.2 billion people with social media accounts, and 5.8 billion mobile phone subscribers Data Reportal, ITU Facts and Figures). The average daily time spent online by users worldwide in 2024 was 6 hours 38 minutes (Statista Daily Time Spent Online).

This astounding growth has released the transformative but previously mostly latent social effects of electronic communications, and it has significant implications for places because everyday life everywhere is now caught in an electronic web.

The first electric communications were by telegraph, invented in the 1840s, which made it possible to deliver messages faster than a messenger. This was followed by a century of slow innovation as telephones, then radio television and electronic technologies insinuated themselves into society. In the 1960s, when radio and television were in their heyday, Marshall McLuhan realized that innovations in media of communication had social effects that went well beyond the convenience of new technology. Printing, after it was introduced in Europe in the 15th century, hadn’t just provided an easier way to copy manuscripts than doing it by hand, it made possible the mass production of books and documents, which democratized literacy and education, and fostered the orderly, rational and detached ways of thinking that lie behind most practices and institutions of modern society.

Electronic media, McLuhan argued, are fundamentally different because they shrink distance by communicating at light speed, circling the world in seconds, turning it back on itself in “a global embrace” in which “we everywhere resume person-to-person relations as if on the smallest village scale.” They create a new version of preliterate societies where emotional engagement and feelings prevail over reason and evidence. He was not enthusiastic about this. “The global village,” he once declared in a moment of remarkable prescience, “is a place of very arduous interfaces and very abrasive situations” (cited in McLuhan and Staines, 2003: 265). In short, electronic media are displacing print media and the social order they have supported for half a millennium.

In spite of their deep intrusions into everyday life, the impact of electronic technologies on the landscapes of places is mostly incremental and minor: cell phone towers and satellite dishes; server farms in innocuous buildings in out of the way locations; fibre is mostly buried, wireless signals pass through walls. Instead it is sense of place, or how places are known and experienced, that they affect. They do this in diverse ways, in some cases obviously and in others indirectly. These are the early stages of the electronic internet age: the following list, which summarize the place impacts of electronic media that can be identified, is necessarily tentative and provisional.

• They simply undermine sense of place. No Sense of Place was the title Joshua Meyrowitz used for his book elaborating McLuhan’s ideas about the impact of radio and television, because these communicate the same top-down messages to mostly passive audiences regardless of where they are. The internet and social media differ because they are participatory rather than passive, anybody can have their say online (which is probably a reason for their enormous popularity). But they also also have no sense because where the influencers and their followers actually are is of no consequence.

• The internet is placeless. It is separate realm detached from geography, where communities consist not of neighbours who know one another, but of individuals have similar views about truth and reality could be located anywhere. For all the language of home pages and web sites, it has no places.

• The erosion of everyday place experiences. Sharon Kleinman has called this “displacing place” because individuals communicating through their devices are distracted, not quite present in the place. On a slightly larger scale electronic media intrude into most everyday activities – writing, reading, banking, shopping, photography, driving, booking flights and concerts. In this respect electronic media have displaced place by reducing the need to go somewhere to interact with other people.

• A poisoned, exclusionary sense of place is facilitated. A poisoned sense of place develops when connections to a place become so narrow and intense that outsiders are seen as undesirable, and in extreme cases to be removed from it. The placeless echo chambers of social media have fostered such exclusionary attitudes, which have in several instances been transposed into violent actions in actual places.

• Breadth of place experience replaces depth of place experience. In combination with rapid air travel (aircraft are flying computers, which shrink distance and fly in and out of non-places) electronic media have facilitated inexpensive travel, which is a form of voluntary displacement, through online booking that has made in possible for many people (there are more than a billion international tourist arrivals a year) to directly experience many different and exotic places even as it shrinks the apparent distances and differences between them. This is a substantial change from previous eras when travel was expensive, difficult and slow, and the majority of people spend most of their lives in one or two places.

• Smart mobs. A smart mob is the crowd of people who don’t know each by act together in response to online promotions or memes of some attraction, place or event. They contribute, for example, to overtourism at places that are apparently on everyone’s bucket list, where they can take selfies to post online.

• The global is reduced to the hyperlocal. Electronic media, for instance in news coverage, tend to shrink them to what is local on the smallest scale; they make everywhere, no matter how distant or exotic, seem nearby by focussing on specific details and effects on individuals. This is a particular aspect of simplification.

• Simplification of identities of places. Electronic media tend to simplify complex issues and large places (cities and regions) to video bites, snapshots and brief descriptions that can be conveyed on little screens and short messages. For tourists this is perhaps related for travel that is primarily to collect place visits and take selfies.

• Emphasis on emotions and feelings over evidence. This general characteristic, which McLuhan identified as central to the global village, is manifest in the frequent attention to feelings, for instance in brief interviews of individuals coping with widespread destruction caused by wildfires, or conflicts. The larger causes and processes affecting places, which are difficult to convey in easily accessible formats, are dealt with briefly. The emphasis on feelings also contributes to the way social media facilitate the spread of misinformation, for instance denial of climate change, because evidence is treated as less important than opinions based on feelings, .

• Openness of places to the world. Places have always been both open to the world and openings to the world. When information travelled slowly and was edited, as in newspapers, this openness was constrained. Electronic media, especially the internet, have made places wide open to the world. News from everywhere now arrives as a constant flow with few or no constraints. At the same time almost every aspect of local and personal life can be widely shared, even with others on the far side of the world.

The places we currently live in and experience, including most of those constructed to accommodate population growth since 1950, been created in accordance with ideas about the organization of spaces, roads and activities that were developed in an age when print media and its rational foundations prevailed. It is too soon to know with clarity where the shift from this to a global village immersed in electronic media might lead, though current political developments give hints of the sorts of upheavals that can happen when conventions are pushed aside. What is clear is that the enormous global popularity of the internet and social media indicates that electronic media already intrude deeply into everyday life in places everywhere. In some ways they have enriched place experiences by making information about them so readily available and allowing individual experiences to be widely shared. In other respects, they have weakened attachments and changed relationships to place, at least to the extent that the more time we spend alone online, in the placeless often misinformed world of the internet, the less time and attention we have to experience places in the real world.

Comments

What I have suggested in this essay is that the character of both individual and shared experiences of places has changed since 1945 because they have been caught in the backwash of several exceptional worldwide social transformations. Unprecedented population growth means that the great majority of neighbourhoods in the world are now urban and less than eighty years old, while continual development and redevelopment of existing places dramatically remakes their identities. Climate change means that past weather in localities is an increasingly poor indicator of future conditions. and is pushing an unprecedented burden of responsibility for mitigation and adaptation onto places at every scale from neighbourhoods to nations. Electronic media seem to distract us from where we are in numerous different ways that generally seem to undermine the importance of place. The risk of place annihilation is a constant background presence.

Furthermore, the global scale of these changes suggests that they are largely indifferent to diplomatic solutions, political ideologies, cultural attitudes or technological fixes. Indications are that in the not too distant future they will present serious challenges for municipalities, cities and regions as populations age and decline, extreme weather becomes more aggressive, and social media spread misinformation about causes and solutions.

Place is a fundamental and adaptable aspect of human life, not easily pushed aside. These changes, for all their extent and scale, have not completely undermined continuity. Place names, and roads and streets that have been rights of way for centuries, have not disappeared; maps made at the height of the print era in the 18th century have a strong resemblance to electronic maps of the 21st century; local histories and customs of places are widely celebrated. What they have done is to ensure that most place experiences are now unlike they were eighty years ago because they are urban, encompass a range of different places, and are continually shifting their forms. But probably the most important conclusion is that, just as climate change means that past weather is no longer a useful indicator of future weather, so past experiences and conventional ideas about place have limited relevance for the present and future.

References

Arendt, Hannah, 1978 The Life of the Mind, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich

Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 2025 https://thebulletin.org/doomsday-clock/2025-statement/

Hansen, J., et al, 1981 “Climate impact of increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide” Science, 213, 957-966, accessed at https://pubs.giss.nasa.gov/abs/ha04600x.html.

Kleinman, S. (Ed) (2007) Displacing place: mobile communication in the twenty-first century. New York: Peter Lang

McLuhan, M. (1964) Understanding Media: the extensions of man, Scarborough, Ontario: A Mentor Book, New American Library.

McLuhan S and Staines D (eds) (2003) Understanding Me: Lectures and Interviews/Marshall McLuhan.Toronto: McLelland and Stewart.

Meyerowitz, Joshua, 1985 No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behaviour (London: Oxford UP)

Our World in Data https://ourworldindata.org. This is an excellent single source for data and diagrams about population growth, fertility, urbanisation, the internet, and climate change.

UNESCO (1972) Convention Concerning the Protection of World Cultural and Natural Heritage. https://whc.unesco.org/en/conventiontext/.

UN World Urbanization Prospects https://population.un.org/wup/

UN World Population Prospects https://population.un.org/wpp/

UN World Fertility Report 2024 https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/