This post explores the idea that “displacement,” a word most commonly used in a negative sense to mean the forced uprooting of people, is better understood as a broad concept that describes a wide range experiences that involve feeling out of place. Displacement happens whenever we choose to move or are forced to move from one place to another. From a geographical perspective it includes a wide range of experiences that involve some feeling of outsideness. Forced displacement is an extreme version of these. More muted versions happen for anyone who chooses to migrate to another country, move to a different city, or live as an expat in a foreign country.

Notions of Displacement

The broad idea of displacement is apparent in the way it is used as a descriptive term in several disciplines, without negative connotations. In geology it refers to the relative movement between the two sides of a fault. In medicine it refers to the form and extent of separation in a bone fracture. In geometry and physics it is a vector quantity that describes the direction and straight line distance an object has moved from its original location. In literature it refers to any narrative that engages with enslavement, exile, uprooting, migration or emigration.

From a geographical perspective, displacement can be understood as any experience of being an outsider, when you are disconnected from your familiar home place, whether a dwelling, a neigbourhood, region or country. Geographical displacement is inextricably linked with sense of place because detachment from or loss of place both reveals and reinforces the significance of attachment to place.

Types of Displacement

Different types of geographical displacement can be identified according to whether they have been forced or are voluntary, whether they are enduring or temporary, and according to their causes. Here I have ordered them from the most intense outsideness, in which people have been forcibly and permanently uprooted, to the gentlest, in which the modest outsideness experienced as a tourist serves as a source of pleasure. Actual displacements may be the result of combined causes, and what was expected to be temporary can become permanent.

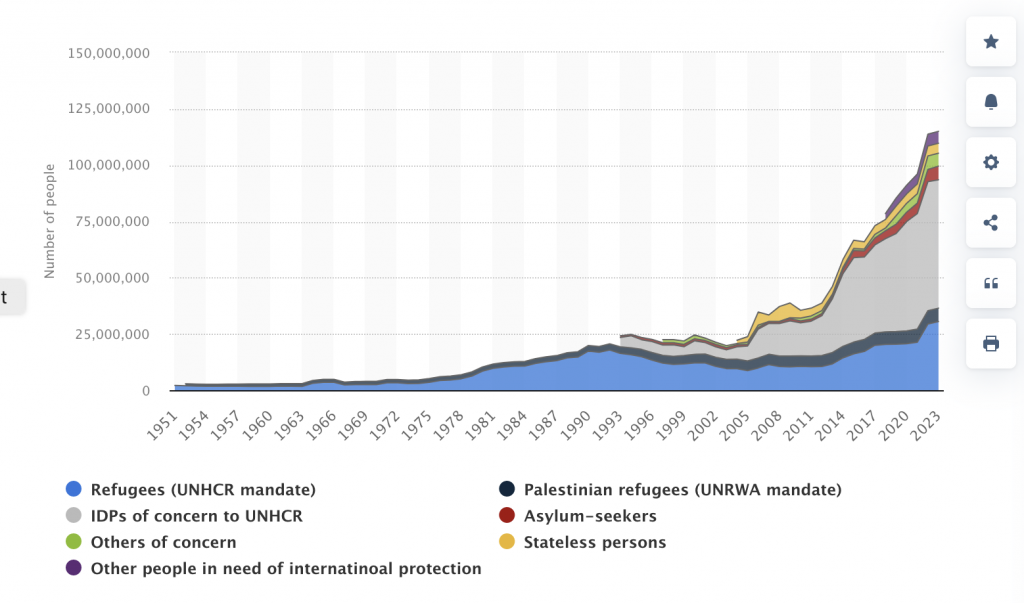

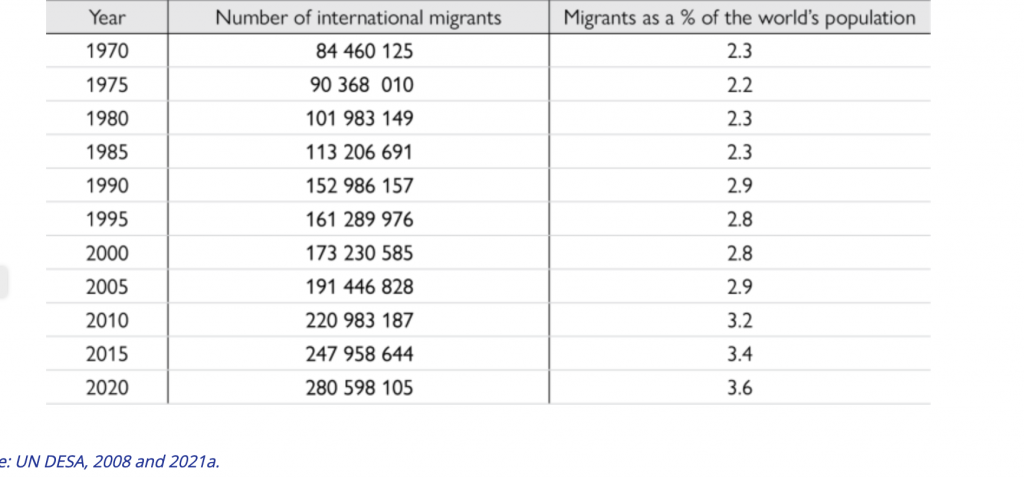

I have included some counts of displaced persons, mostly from agencies associated with the UN. These should be regarded cautiously because it is not always clear what they refer to and whether there is double counting. Nevertheless they indicate that processes of displacement, which have a history as long as civilization itself, are currently widespread and that since the middle of the 20th century they have apparently increased faster than population growth.

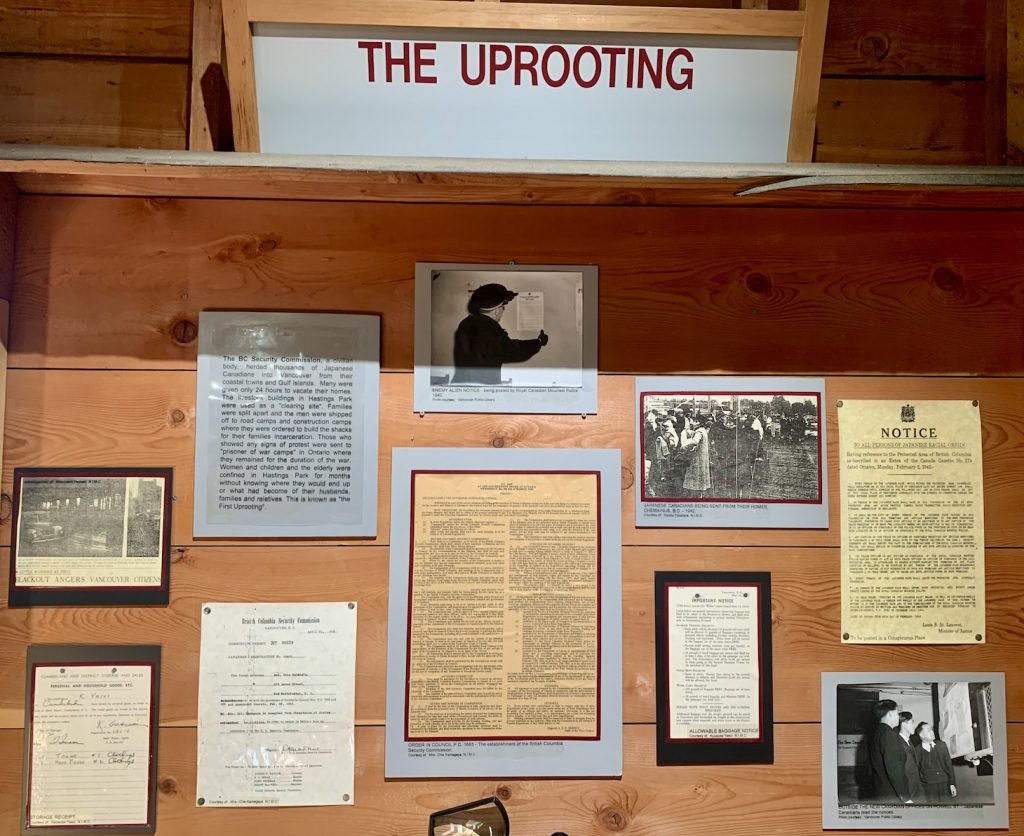

Forced Displacement

Forced displacement includes all involuntary or coerced movement of people away from their homes or home region. It is the central concern of the United Nations Refugee Agency (UNHCR), which has collected data and provided assistance to refugees since 1950, and which reviews global trends every year. There is also an extensive research literature about forced displacement that emphasizes issues about inequality and injustice (a summary is available here An academic overview is Peter Adey et al, 2020 The Handbook of Displacement, Springer Nature)

• International Forced Displacement. UNHCR, defines this as”a result of persecution, conflict, generalized violence or human rights violations” that have forced refugees to flee their country. This sort of displacement is effectively permanent, and breaks attachments to place both in terms of home community and in national identity. There were about 2.1 million refugees in 1951, when UNHCR began to keep records. By 1993 there were 20 million, and by the end of 2023 the number had risen to almost 38 million. In addition, in 2023 there were 6.9 million asylum seekers, and another 5.8 million people considered to be in need of international protection (UNHCR, PopStats)

• Internal Forced Displacement refers to those forced to leave homes or places of habitual residence to avoid armed conflict, violence, or environmental disasters, but who remain in the country of their birth. For some there is the possibility of returning home and rebuilding. There were 4 million internally displaced people in 1993 when UNHCR started counting; the number had risen to 68.3 million at the end of 2023 (UNHCR Figures).

• Climate Change Displacement. UNHCR notes that 60% of refugees and internally displaced persons, perhaps 20 million to 30 million in 2023, are from countries, mostly in sub-Saharan Africa, and East and South Asia, that are especially vulnerable to environment hazards related to climate change (UNHCR Climate Change). These displacements might at first be temporary, for instance as droughts ease, but they are expected to grow in extent and become permanent as the climate crisis intensifies The World Bank projects that by 2050 216 million will be internally displaced because of climate change, and the UNDP suggests that climate change displacement might impact as many as one billion people by 2100 (UNDP 2017 Climate Change, Migration and Displacement, p.10).

Permanent displacements as a consequence of climate change are already apparent in developed countries because of rising sea levels, repeated extreme weather events and threats from wildfires (see e.g. Jake Bittle 2023 The Great Displacement: Climate Change and the Next American Migration, Simon and Schuster) These displacements are now being managed through policies of ”planned or managed retreat” (see reviews here and here). These are, in other words, policies of planned displacement.

• Temporary Environmental Displacement happens because of natural disasters such as floods, earthquakes, hurricanes, wildfires and storm surges. They include precautionary evacuations ahead of forecast disasters, some in recent cases involving several million people. These can extend into much longer but still temporary displacements wherever infrastructure and buildings need to be rebuilt before people can return home.

• Development displacement because of large scale developments, such as the construction of dams and reservoirs, mines, airport expansions, expressways, deforestation, etc, that involve expropriation and eradication of existing settlements. This was widespreas in the 20th century, but is now often contested and continues on a smaller scale.

• Urban development displacement caused by the redevelopment of urban areas, renovictions, and, more subtly, gentrification. These are permanent and mostly impact poor or disadvantaged residents A recent argument has been made by Hirsch, Eizenberg and Jabereen (2020) that that there are strong similarities between urban displacement in the Global North and forced displacement in the Global South in terms of the exercise of power, coercion, and the relatively low socio-economic status of those displaced.

• Homelessness – a homeless person is somebody displaced from their habitual place of residence. There is no standard measure of the numbers involved, but Wikipedia (using data from the World Economic Forum) suggests that worldwide there may 150 million homeless people.

Voluntary Displacement

Voluntary displacement is the outcome of choices made to move to an unfamiliar place, whether to find a better life, to study, to enjoy living abroad, or to travel for pleasure. The line between forced and voluntary is not always clear, not least because some choices to move may be made in anticipation of forced displacement.

• International Migration has historically been a significant form of enduring voluntary displacement as people have moved to places that offered improved lifetime opportunities. The 2024 World Migration Report estimates that currently about 281 million people in the world (3.6% of the global population) were born in a country other than the one they now live in – in other words are voluntarily displaced. That Report in 2000 (see p.4 of the pdf) made the important comment that since the 1970s the annual rate of global population growth had been consistently outpaced by the growth of international migration. This trend has continued. The world’s population grew by by 48% between 1990 and 2020, but international migration grew by 83%.

• Displacement for Transnational Employment (foreign workers and students). These temporary forms of displacement may last for several years for students but only a few months for seasonal employees. There are estimated by the World Bank to be about 184 million migrant workers in the world who send remittances to family in their home nations, and there are about six million international students.

• Expatriate Displacement. Expatriates include both those who have long-term professional work assignments in other countries, and those, such as retirees or people with flexible employment, who choose to live permanently in a foreign country without renouncing their nationality. One estimate by Finaccord, a business consultancy specializing in services to expats, was that in 2017 there were 66.2 million globally, projected to increase to 85 million in 2021.

InterNations, which considers itself to be the largest expat network, has 2.5 million members in 390 cities around the world. It notes in one entry that spending so much time away from their original home can create an identity crisis for expats. The longer you’re away and the more places you move to, the less attached you can feel to any nationality, and In your new home it may be difficult to identify as a local if you do not share the nationality of the residents.

• Churning and Displacement. Churning is the widespread, continual restlessness that seems to underlie modern urban societies, with many people moving every year, either to a different addresses in the same city or to different different cities or regions in the same country. Some idea of the scale of this can be gleaned from national censuses. On average individuals in the US move 11.5 times in their lifetime. In the UK almost a quarter of households have lived in their home for three years or less. In Canada just over a third of the population (roughly 12 million) moves to a new dwelling every five years, with about half of those moving to a new city or province. Most of these relatively gentle displacements are chosen, presumably to find a different or better everyday life experience in a new place that is culturally familiar but is geographically and socially unfamiliar.

• Tourism and Travel Displacement is the extreme case of voluntary displacement because it involves brief experiences of outsideness, is entirely by choice, and so many participate in it. A major motivation for tourism is to spend time in a place that is unfamiliar in order to enjoy and appreciate different weather, languages, foods, and ways of doing things. In other words, to enjoy an experience of displacement that is temporary. Numerous websites promote the benefits of travel and getting away from home. They refer to new challenges, experiences you can share when you return, fresh perspectives, a break with routine, and most significantly for understanding tourism as a form of displacement, stepping outside your comfort zone, and development of a better appreciation for what you have at home. This is displacement with the comfortable insurance of soon returning to your native country or home place.

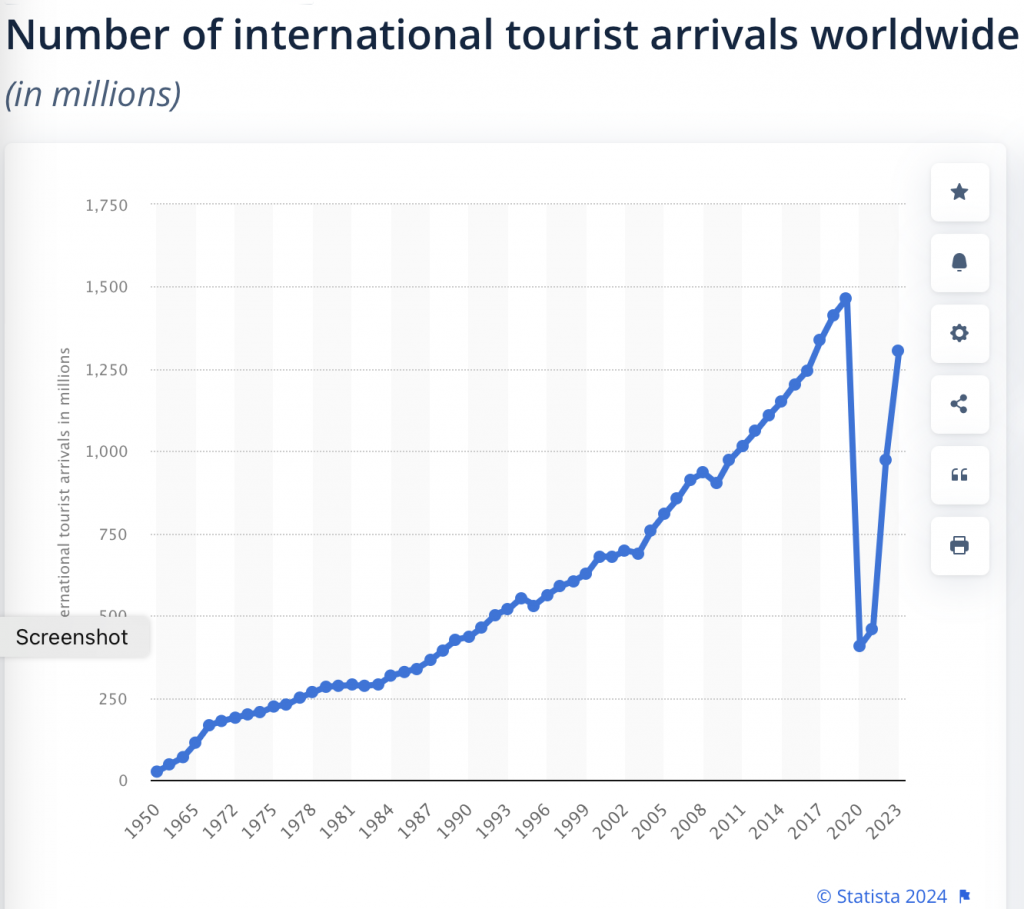

The sheer scale of international travel is significant. In 2023 there were 1.3 billion international arrivals (overnight stays of at least one night and less than 12 months, without remuneration), though this includes individuals who travelled to several different countries. The number has grown almost continuously for decades – in 1990 it was 435 million, it quadrupled to 1.46 billion by 2019, dropped to 406 million in 2020 during COVID, and has now climbed back to pre-COVID levels (see Statista).

Three Concluding Comments

First, given the broad perspective I have proposed, displacement or the experience of somehow being an outsider, is a widespread and diverse way of encountering the world.

Second, while there have always been people forcibly uprooted because of violent conflicts and oppression, or voluntarily displaced by pilgrimages and rural-urban migration, there are strong indications in the growing numbers of refugees, tourists, and now particularly climate migrants, that displacement is becoming an increasingly prevalent companion to experiences of place.

Thirdly, and more theoretically, displacement reinforces the significance of attachment to place by exposing its absence. Loss of place in forcible displacement makes clear the significance of connections to place that might previously have been taken for granted. Encounters with unfamiliar places in voluntary displacement either raise the challenge of establishing sense of place somewhere new or simply reveal the merits of different place identities.

Place attachment is knowing and being known somewhere, feeling at home, being in a neighbourhood or community where you can find your way around, feel comfortable with the language and everyday ways of behaving, of being inside a place. Displacement involves place detachment, an experience of outsideness, an absence of familiarity with somewhere. This absence reveals the value and significance of place. It seems that displacement and sense of place are intertwined. Displacement is experienced when sense of place is taken away, and sense of place is made explicit by experiences of displacement.