“Before you can write a good plot, you need to write a good place,” says the Swedish novelist Linn Ullman. Writing well about places is a skill required not only by novelists, but also by travel writers and all those who want to communicate their enthusiasm about the diversity and similarities of places.

Ullman, the daughter of Ingmar Bergman, considers her own life as “somewhat placeless” because she grew up in so many different places. But she thinks that precisely because of this she likes authors who are very place oriented. She admires Canadian Nobel prize-winning author Alice Munro, and specifically a comment Munro wrote in her story Face: “Something had happened here. In your life there are a few places, or maybe only one place, where something has happened. And then there are the other places, which are just other places.” (This illustration is from the Atlantic Monthly article about Linn Ullman)

Ullman, the daughter of Ingmar Bergman, considers her own life as “somewhat placeless” because she grew up in so many different places. But she thinks that precisely because of this she likes authors who are very place oriented. She admires Canadian Nobel prize-winning author Alice Munro, and specifically a comment Munro wrote in her story Face: “Something had happened here. In your life there are a few places, or maybe only one place, where something has happened. And then there are the other places, which are just other places.” (This illustration is from the Atlantic Monthly article about Linn Ullman)

Munro’s stories are set in small communities in southern Ontario, where whole worlds play out. Every story has to happen somewhere. You do not have a story of life without an actual place, Ullman declares. “You can’t separate one from the other.”

It isn’t easy to write place

If you start off trying to write a general, all-embracing account of a somewhere without any clear sense of how to do it, you will probably either grind to a frustrating halt or end up with a sterile inventory that conveys nothing of the place’s identity. To write effectively about a place you have to find a hook, an entry point. Robert Pirsig in Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, which is an account of a search for quality in things he encounters as he makes his way across America on a motorbike, provided a simple example I often think about. Somewhere along his way, perhaps in Montana, he took a teaching job, and asked his students to write a short essay about the qualities of the town they live in. One soon comes back and tells him: “I can’t do this. I don’t know where to start.” Pirsig suggests writing about the main street. Back comes the student a day later and says: “I still can’t begin.” Pirsig says: “Write about the stones in the wall of city hall.” A few days later the student tells him: “It’s amazing. Now I can’t stop writing.”

A sign with important advice at a State Park in Montana, 1998.

Finding hooks isn’t easy. Not because they are obscure, but because most of us are not used to looking carefully and thoughtfully at the world around us, and noticing the significance that lies in details. To write well about places (or to photograph them) you first have to be able to see them clearly. In effect that means reading their landscapes with a critical eye. This is easy to say but actually requires an effort to overcome a tendency to ignore places that are inconspicuous because they are so familiar, and also to overcome deeply ingrained habits of seeing things according to conventional categories about what is pretty or ugly or important

Two Guides for Reading Landscape and Place

I know two useful guides for reading landscape and place in this critical way. One is a website How to Read a Landscape that was prepared in 2008 for of a course taught by William Cronon, an environmental historian at the University of Wisconsin. The course is oriented towards historical research, and pays homage to Aldo Leopold’s Sand County Almanac, which was written about a nearby region in Wisconsin. For Cronon landscapes, both rural and urban, are documents that contain invaluable historical and environmental information for those who know to decipher and interpret it. Although Cronon’s website claims that it is not intended as a comprehensive guide, it does consist mostly of very practical suggestions from the students who participated in the course. These range from advice about the equipment needed to start making observations of somewhere, to suggestions about unpacking layers of meaning and the relationships between modes of production and consumption. Landscapes are clues to culture, to borrow a phrase from the geographer Peirce Lewis in his essay “Axioms for Reading the Landscape.” They are what a culture makes for itself rather than what it says about itself and are therefore honest statements about cultural values.

The other guide is Linda Lappin’s 2015 book The Soul of Place: A Creative Writing Workbook – Ideas and Exercises for Conjuring the Genius Loci. She is a novelist and teacher, and her orientations are towards creative and travel writing. Her book offers a number of exercises for recognizing and writing about genius loci and what she calls the personal geography of places. Lappin offers many questions that can be asked of a place – for instance: how might the natural resources and climatic conditions affect the livelihoods of the people? What color is the light? What succeeds in creating a sense of intimacy? How does it feel underfoot? How do authorities reveal themselves? And she proposes a number of short writing exercises that can attempt to answer these sorts of questions. She also suggests many possible foci (which I called hooks above) for writing about a place, for instance, a bridge, a bus station, a door, a parking area, a laundromat, a shopping mall, a tree, stairs, traffic in motion, where a saint has died. A well-chosen focus can be a microcosm for the identity of the place.

The other guide is Linda Lappin’s 2015 book The Soul of Place: A Creative Writing Workbook – Ideas and Exercises for Conjuring the Genius Loci. She is a novelist and teacher, and her orientations are towards creative and travel writing. Her book offers a number of exercises for recognizing and writing about genius loci and what she calls the personal geography of places. Lappin offers many questions that can be asked of a place – for instance: how might the natural resources and climatic conditions affect the livelihoods of the people? What color is the light? What succeeds in creating a sense of intimacy? How does it feel underfoot? How do authorities reveal themselves? And she proposes a number of short writing exercises that can attempt to answer these sorts of questions. She also suggests many possible foci (which I called hooks above) for writing about a place, for instance, a bridge, a bus station, a door, a parking area, a laundromat, a shopping mall, a tree, stairs, traffic in motion, where a saint has died. A well-chosen focus can be a microcosm for the identity of the place.

Lappin also discusses what she calls the house of the self, the importance of the picturesque and the sublime, and both postcards and tweets as ways of conveying genius loci. However, for me her most substantial advice is about “Reading the Landscape.” She stresses the importance of identifying patterns and textures, ways of finding images to convey the impressions landscapes have on you, looking for evocative suggestions in place names, and William Least Heat Moon’s idea of “deep maps.” By deep map he means an intensive vertical examination of one place (in his case it is the region around the geographical center of the USA, which is in Kansas), in all its manifestations of genius loci, all its histories and stories and imaginative possibilities.

A store in Washington D.C. that blends writing and place.

Seeing, Thinking and Describing Places

I indicated some of my own thoughts about reading landscape some years ago in an essay “Seeing, Thinking, Describing Landscapes” (available online at Academia.edu). While I emphasized the importance of seeing clearly, albeit in a much briefer and more abstract way than Lappin and Cronon, my main point was that seeing, thinking and describing/writing are activities that reinforce one another, often through a series of iterations. They involve what the Victorian art critic John Ruskin described as “a curiously balanced condition of the powers of the mind.” In other words, seeing clearly involves thinking carefully, responding to patterns in what has been seen, relating observations to theory, reading what others have written, and finding effective language to express your interpretations and observations. Indeed the intention of writing will inevitably direct attention towards certain aspects of a place depending on whether the aim is prepare a planning report, a short story or a travel blog. Moreover the act of writing will often reveal shortcomings in thoughts and observations that have to filled by going back to look again from a different perspective.

Final Comments

Every story has to happen somewhere. I believe the exercises in Lappin’s The Soul of Place, and the suggestions in Cronon’s website, are excellent foundations for learning to read and then write about places and their landscapes. To follow every step they propose would, however, be very challenging. I find it easier to pick and chose from the types of questions and hints they offer, and to allow these to challenge my habits of thinking and to help me to see with what Goethe called “clear fresh eyes.”

NOTE: I see similarities between learning to read landscapes and learning to draw as it has been proposed by Kimon Nikolaides in The Natural Way to Draw and Betty Edwards in Drawing with the Right Side of the Brain. The gist of their argument is that anyone who can use a pencil to write has the motor skills needed to draw well; what most of us lack is the ability to observe carefully. If you can see well, you can draw well, and they both offer sequences of exercises that facilitate drawing well through seeing well. Nikolaides thought it might take months to achieve substantial results, but Edwards shows more encouragingly that for some people a breakthrough can happen with only five days of focused effort.

NOTE: I see similarities between learning to read landscapes and learning to draw as it has been proposed by Kimon Nikolaides in The Natural Way to Draw and Betty Edwards in Drawing with the Right Side of the Brain. The gist of their argument is that anyone who can use a pencil to write has the motor skills needed to draw well; what most of us lack is the ability to observe carefully. If you can see well, you can draw well, and they both offer sequences of exercises that facilitate drawing well through seeing well. Nikolaides thought it might take months to achieve substantial results, but Edwards shows more encouragingly that for some people a breakthrough can happen with only five days of focused effort.

References and an acknowledgement:

Edwards, Betty 1989 Drawing with the Right Side of the Brain

Fassler, Joe 2014 “Before you can write a good plot, you need to write a good place” An interview with Linn Ullman, Atlantic Monthly April 2014 available online here

Goethe, J.D 1970 (1786-88) Italian Journey (trans W.H. Auden and E. Mayer) (Penguin)

Lappin, Linda 2015 The Soul of Place: A Creative Writing Workbook – Ideas and Exercises for Conjuring the Genius Loci. Palo Alto: Travelers’ Tales

Lewis, Peirce, 1979 “Axioms for Reading Landscape” in Don Meinig (ed) The Interpretation of Ordinary Landscapes, Oxford University Press

Nikolaides, Kimon, 1941 The Natural Way to Draw, Boston: Houghton Mifflin

Pirsig, Robert 1974 Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance

Relph, Edward 1984 “Seeing, Thinking and Describing Landscape” in Environment, Perception and Behavior, eds. T. Saarinen, D.Seamon and J. Sell, University of Chicago, Department of Geography Research Series, No. 209, pp.209-223. Available here at academia.edu.

Ruskin, John, 1843 Modern Painters Vol III, Chapter 17, Section 5

And my thanks to Linda Lappin who generously sent me a copy of her fascinating book which has got me reading landscapes in all sorts of new ways.

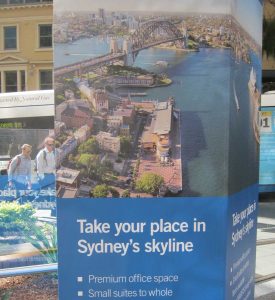

• Place as primarily a material attribute of the world. A place is some thing somewhere – a room, a building, a neighbourhood, a park, a city, a mountain, It is a fragment of geography. This interpretation prevails in architecture, urban planning, traditional regional geography, ecology, and placemaking. This material idea of place is conveyed in this advertisement for a proposed development in Sydney in 2014.

• Place as primarily a material attribute of the world. A place is some thing somewhere – a room, a building, a neighbourhood, a park, a city, a mountain, It is a fragment of geography. This interpretation prevails in architecture, urban planning, traditional regional geography, ecology, and placemaking. This material idea of place is conveyed in this advertisement for a proposed development in Sydney in 2014. • Place as primarily a way of being attached to or connecting with the world and with others. These connections might be through habitual actions and familiarity, emotional engagements, or participation in local communities. At a personal scale these connections are regarded as extensions of the body; at a social scale they are variously manifest in place names that provide a means of communicating shared place identities and in the myriad ways in which we participate in communities . This interpretation prevails in environmental psychology, sociology, anthropology, some philosophical studies, and theology. This banner for Fairfield Gonzales Community Association in Victoria B.C. explicitly captures the idea of place as connection,

• Place as primarily a way of being attached to or connecting with the world and with others. These connections might be through habitual actions and familiarity, emotional engagements, or participation in local communities. At a personal scale these connections are regarded as extensions of the body; at a social scale they are variously manifest in place names that provide a means of communicating shared place identities and in the myriad ways in which we participate in communities . This interpretation prevails in environmental psychology, sociology, anthropology, some philosophical studies, and theology. This banner for Fairfield Gonzales Community Association in Victoria B.C. explicitly captures the idea of place as connection, • Place as primarily a socio-economic construct. Places are distinctive local nodes in networks of economic relationships that operate at regional and global scales. This economic interpretation of place prevails in the work of political-economic geographers who are critical of neo-liberalism. Paradoxically, it is also the foundation for business studies that advocate place branding and other strategies that are intended to generate a competitive advantage for particular places. This illustration is an advertisement for HSBC from August 2015. The text reads, in part: “Today’s successful businesses work around the clock with partners at home and around the world…HSBC offers your business global reach and local expertise.”

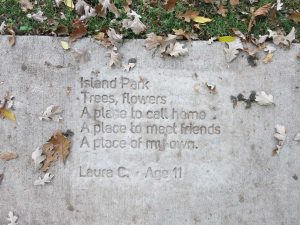

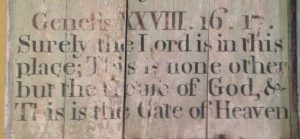

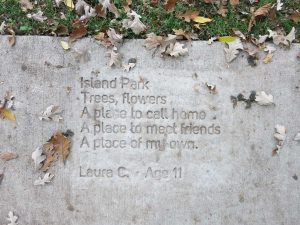

• Place as primarily a socio-economic construct. Places are distinctive local nodes in networks of economic relationships that operate at regional and global scales. This economic interpretation of place prevails in the work of political-economic geographers who are critical of neo-liberalism. Paradoxically, it is also the foundation for business studies that advocate place branding and other strategies that are intended to generate a competitive advantage for particular places. This illustration is an advertisement for HSBC from August 2015. The text reads, in part: “Today’s successful businesses work around the clock with partners at home and around the world…HSBC offers your business global reach and local expertise.” • Place as primarily a lens through which to interpret experiences of the world. This is associated with the phenomenological view that place is the first of all things because whatever we do has to be done in places, and that places are territories that gather meaning. This interpretation prevails among philosophers and humanistic geographers aiming to disclose the sort of subtle and profound character of place experience that is suggested in this poem by Laura C. set in the ground in a park in Fargo, North Dakota.

• Place as primarily a lens through which to interpret experiences of the world. This is associated with the phenomenological view that place is the first of all things because whatever we do has to be done in places, and that places are territories that gather meaning. This interpretation prevails among philosophers and humanistic geographers aiming to disclose the sort of subtle and profound character of place experience that is suggested in this poem by Laura C. set in the ground in a park in Fargo, North Dakota.

To enable us (those who are interested? everybody?) to enhance our appreciation and enjoyment of the places we experience in everyday life or through travel. And to do this especially by clarifying and communicating the character of place experience and the diverse identities of places. This sign was in a store window in Victoria, British Columbia.

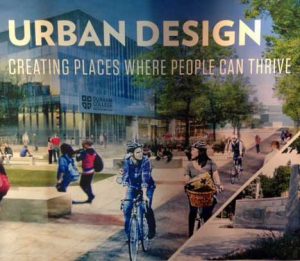

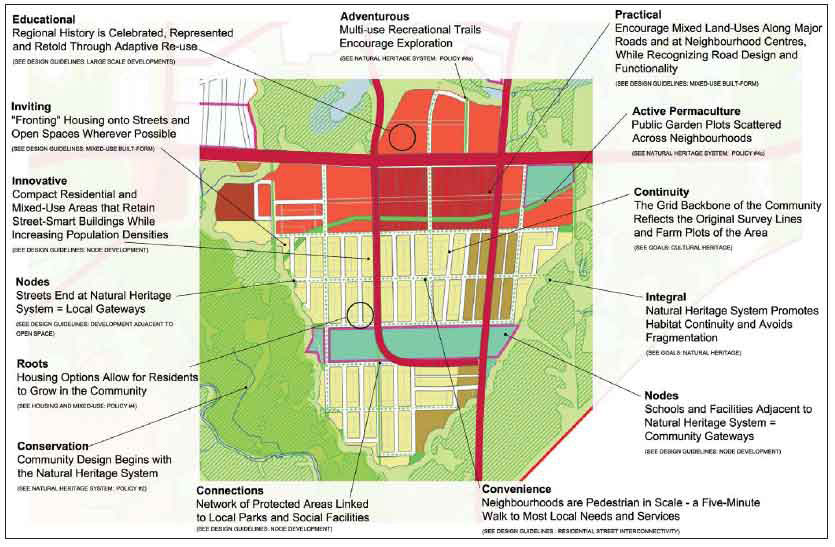

To enable us (those who are interested? everybody?) to enhance our appreciation and enjoyment of the places we experience in everyday life or through travel. And to do this especially by clarifying and communicating the character of place experience and the diverse identities of places. This sign was in a store window in Victoria, British Columbia. This normative motive is particularly associated with the assumption that place is primarily an aspect of the material world. It has many specific versions. It might involve designing built-environments that aim to improve place and place experiences. It might involve finding ways to live more compatibly with natural environments by identifying the ways that place gathers a continuum of nature-body-mind-society. It might involve finding ways to protect or recover heritage and the qualities of inherited places. It might involve identifying ways for communities to become more resilient in the face of social, economic and environmental changes.

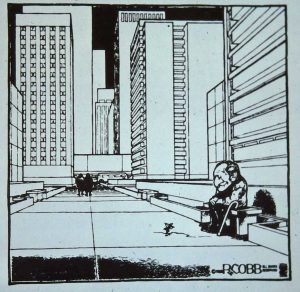

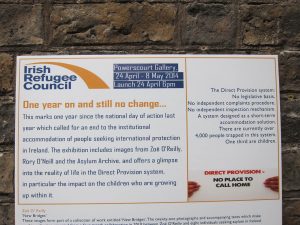

This normative motive is particularly associated with the assumption that place is primarily an aspect of the material world. It has many specific versions. It might involve designing built-environments that aim to improve place and place experiences. It might involve finding ways to live more compatibly with natural environments by identifying the ways that place gathers a continuum of nature-body-mind-society. It might involve finding ways to protect or recover heritage and the qualities of inherited places. It might involve identifying ways for communities to become more resilient in the face of social, economic and environmental changes. To improve understanding of community and social relationships to place. An aspect of this is suggested by the posted in Borough Market in London in 2012. An especially important aspect of it has to with understanding and appreciating the grief of displaced communities experiencing rootshock, and for communities in which there is some sense that a distinctive place identity is being eroded by social, economic and/or technological processes, or more specifically by new developments, that fail to respect distinctiveness.

To improve understanding of community and social relationships to place. An aspect of this is suggested by the posted in Borough Market in London in 2012. An especially important aspect of it has to with understanding and appreciating the grief of displaced communities experiencing rootshock, and for communities in which there is some sense that a distinctive place identity is being eroded by social, economic and/or technological processes, or more specifically by new developments, that fail to respect distinctiveness. To propose ways to enhance the benefits of economic flows and processes for particular places by branding and otherwise managing their identities as a way to give them a competitive advantage. Many universities, such as the University of Otago in this advertisement that was on the back of a bus in Wellington, have adopted place branding in order to boost recruitment.

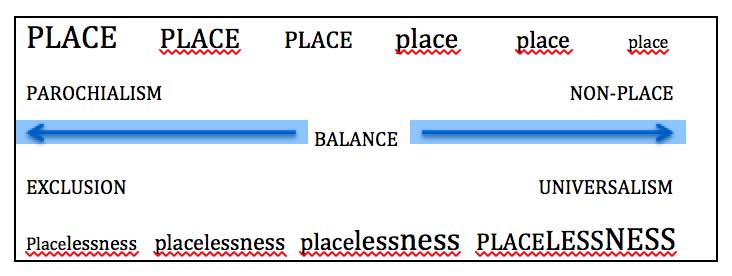

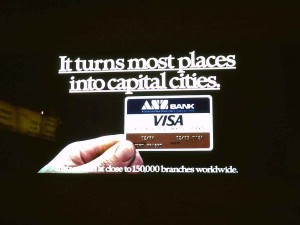

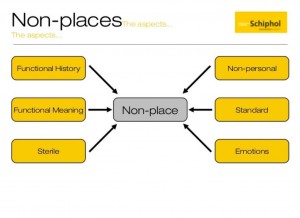

To propose ways to enhance the benefits of economic flows and processes for particular places by branding and otherwise managing their identities as a way to give them a competitive advantage. Many universities, such as the University of Otago in this advertisement that was on the back of a bus in Wellington, have adopted place branding in order to boost recruitment. To clarify what is happening in the world by investigating the interplay of processes and manifestations of placelessness (or non-place) and place. Everywhere is simultaneously different from and similar to places elsewhere (as is suggested in the claim that “There’s no place like this place, anyplace” on Honest Ed’s, a low end department store in Toronto that closed down in 2016), but the character of the balance is infinitely varied. The ways in which this balance is shifting because of increased mobility and electronic communications has become especially important because fundamental place ideas about roots, belonging, and locality are being modified by translocal ways of life and significant engagement with many places.

To clarify what is happening in the world by investigating the interplay of processes and manifestations of placelessness (or non-place) and place. Everywhere is simultaneously different from and similar to places elsewhere (as is suggested in the claim that “There’s no place like this place, anyplace” on Honest Ed’s, a low end department store in Toronto that closed down in 2016), but the character of the balance is infinitely varied. The ways in which this balance is shifting because of increased mobility and electronic communications has become especially important because fundamental place ideas about roots, belonging, and locality are being modified by translocal ways of life and significant engagement with many places.

Distinctiveness pushed to the extreme results in parochialism, exclusionary attitudes, even ethnic cleansing. Such attitudes have to be regarded not just as narrow-minded but as naïve in a world now interconnected by electronic communications, air travel and intermittent epidemics of emergent and other diseases. They will not keep out the next flu pandemic nor protect against tidal surges and ideas communicated on the Internet.

Distinctiveness pushed to the extreme results in parochialism, exclusionary attitudes, even ethnic cleansing. Such attitudes have to be regarded not just as narrow-minded but as naïve in a world now interconnected by electronic communications, air travel and intermittent epidemics of emergent and other diseases. They will not keep out the next flu pandemic nor protect against tidal surges and ideas communicated on the Internet.

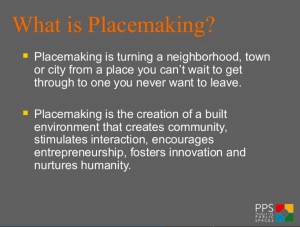

So I went to the Future of Places forum in Vancouver in September 2016 where I heard impressive arguments about placemaking and the importance of designing public spaces, borrowing heavily from the inspiration of Holly Whyte’s Social Life of Small Urban Spaces and Jan Gehl’s Life Between Buildings. The symposium was syncopated with a

So I went to the Future of Places forum in Vancouver in September 2016 where I heard impressive arguments about placemaking and the importance of designing public spaces, borrowing heavily from the inspiration of Holly Whyte’s Social Life of Small Urban Spaces and Jan Gehl’s Life Between Buildings. The symposium was syncopated with a

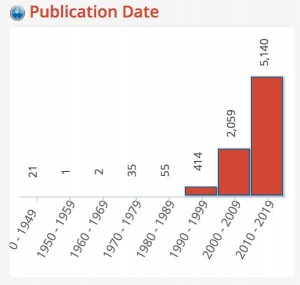

I have read a number of books and articles about placemaking, but unsystematically, and mostly published before 2005. However, when I looked up placemaking in the University of Toronto Library search engine over 7500 books and articles were listed, along with this intriguing bar graph showing numbers of publication by decade (this recent explosion in number of publications is not the norm for every topic – I checked). The recent growth is daunting, so what I will do in this post is to examine the origins and early development of the idea. I haven’t been able to find the publications before 1970 and comments on more recent stuff will have to wait.

I have read a number of books and articles about placemaking, but unsystematically, and mostly published before 2005. However, when I looked up placemaking in the University of Toronto Library search engine over 7500 books and articles were listed, along with this intriguing bar graph showing numbers of publication by decade (this recent explosion in number of publications is not the norm for every topic – I checked). The recent growth is daunting, so what I will do in this post is to examine the origins and early development of the idea. I haven’t been able to find the publications before 1970 and comments on more recent stuff will have to wait.

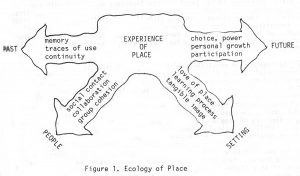

The image on the left is from

The image on the left is from  •

•

The promotion of places has a deep history. Stephen Ward’s 1998 book Selling Places examines, for example, how land in California and Oregon was advertised to attract people to make the hard overland journey across America, and the ways health resorts and spas such as Blackpool and Saratoga Springs attracted visitors a century or more ago, and how suburbs in Britain and America were sold in the 1930s. This romantic illustration of Tunbridge Wells is from London Transport’s Metroland campaign of the 1930s (it was in a 2015 calendar on my office wall). Nevertheless, since 1990 such promotion has become formally named place branding and a widely adopted marketing approach to place. Most cities, and tourist destinations, and many universities and even nations are now branded.

The promotion of places has a deep history. Stephen Ward’s 1998 book Selling Places examines, for example, how land in California and Oregon was advertised to attract people to make the hard overland journey across America, and the ways health resorts and spas such as Blackpool and Saratoga Springs attracted visitors a century or more ago, and how suburbs in Britain and America were sold in the 1930s. This romantic illustration of Tunbridge Wells is from London Transport’s Metroland campaign of the 1930s (it was in a 2015 calendar on my office wall). Nevertheless, since 1990 such promotion has become formally named place branding and a widely adopted marketing approach to place. Most cities, and tourist destinations, and many universities and even nations are now branded.

If somewhere doesn’t have many assets that can be used as the basis for branding, what does exist can be physically amplified or even created, more or less on the build it and they will come principle. This is sometimes done by small towns, such as pseudo-Bavarian Leavenworth in Washington, which adopt attractive foreign identities and thus turn themselves into tourist attractions. At a larger scale it is clear that the Eiffel Tower, the CN Tower in Toronto, and the Sydney Opera House all serve as instant identity markers for those cities, even though they were built for other purposes. A more intentional approach to place branding aims to achieve the same effect by building spectacular destination architecture – a process that has been called

If somewhere doesn’t have many assets that can be used as the basis for branding, what does exist can be physically amplified or even created, more or less on the build it and they will come principle. This is sometimes done by small towns, such as pseudo-Bavarian Leavenworth in Washington, which adopt attractive foreign identities and thus turn themselves into tourist attractions. At a larger scale it is clear that the Eiffel Tower, the CN Tower in Toronto, and the Sydney Opera House all serve as instant identity markers for those cities, even though they were built for other purposes. A more intentional approach to place branding aims to achieve the same effect by building spectacular destination architecture – a process that has been called