In this post I offer a general overview of the range of different ideas about sense of place. Some of its important variations, such as a poisoned sense of place and a global sense of place, I intend to cover in more detail in future posts. I list some references at the end. Topics are:

- Sense of Place as a Distinctive Aspect of Somewhere (=Genius Loci)

- Sense and Nonsense of Place

- Sense of Place as a Faculty for Distinguishing and Appreciating Places

- Variations in Sense of Place over Time

- Different Types of Sense of Place

- Drudgery, Oppression and a Poisoned Sense of Place

- GIS and Measurement of Sense of Place

- A Global Sense of Place

- Sense of Place as a Phenomenological Bridge between Person and World

- Sense of Place as a Neurological Bridge between Self and World

- A Pragmatic Sense of Place

- A Commercial/Retail Sense of Place

I intend to discuss some of these (e.g. Genius Loci, Poison Sense of Palce, Global Sense of Place, Phenomenological and Neurological ideas) in more detail in subsequent posts.

Introduction

‘Sense of place’ has become a popular, feel-good buzz phrase. Google it and you will be directed variously not only to sites on architecture, urban design, and geography but also to sense of place essay writing services (these descriptive essays are common writing assignments based on a particular location where students feel they belong). Making Sense of Place is a group of historical consultants in the U.S. that provides interpretations of cultural and natural history. The essayist on American landscapes, J.B. Jackson wrote dismissively that: “Sense of place is a much used expression, chiefly by architects but taken over by urban planners and interior decorators and the promoters of condominiums, so that now it means very little.” And at an international scale there is a new (since 2013), energetic organization based in Malaysia with the clever name SoPlace that is dedicated to “Mainstreaming Place in the Urban Century” by using a range of social media and hosting conferences that it describes as “World Summits of Sense of Place” with presentations by academics, designers, planners and policymaker , and has plans until 2021 for further SoPlace summits. The aim of SoPlace is to mobilize “the global sense of place fraternity for mainstream impact.”

I came upon this advertisement in a magazine in a waiting room, and was not sure whether ‘sense of place’ here refers to what she is thinking or the chair. In fact, it’s the chair – Matteo Grassi design and make chairs.

In spite of this diverse enthusiasm about sense of place it is not altogether clear what it means. It is often used in two apparently contradictory ways. One refers to a human faculty that grasps the distinctive subtleties of different bits of the world and helps us to find our way around; the other is about particular qualities of bits of the world. So sense of place can be variously regarded as something in our heads, or as a property of landscapes.

My inclination is to understand sense of place from a phenomenological perspective – as a fundamental aspect of everyday life and a connection between person and world. Somewhat to my surprise this idea of sense of place as connectedness or togetherness is getting reinforcement from the research of neuroscientists.

Furthermore, like almost everything to do with place, sense of place shifts across enormous scales – from direct experiences of grandma’s kitchen (a recommended topic for sense of place essays) to an appreciation of the entire globe (as in SoPlace Summits).

And while it is almost always regarded as altogether positive, it is important to remember that sense of place can contribute to negative, exclusionary, even xenophobic attitudes, and ambiguity nicely captured by John Milton in Paradise Lost Book 1:

The mind is its own place, and in itself

Can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.

Sense of Place as a distinctive aspect of somewhere (equals genius loci)

The phrase sense of place is often used to refer to the quality that makes somewhere distinctive. It is the environmental equivalent of saying somebody has a strong personality. For example, Robert Fulford and John Sewell wrote a short book about Toronto in 1971 titled A Sense of Time and Place which was liberally illustrated with photographs of old buildings and streets. It often turns up in tourist and promotional literature with much the same meaning, which is not altogether felicitous. J.B.Jackson, the essayist of American landscapes, remarks in his book A Sense of Place, a Sense of Time (1994) that: “Sense of place is a much used expression, chiefly by architects but taken over by urban planners and interior decorators and the promoters of condominiums, so that now it means very little. It is an awkward and ambiguous translation of genius loci.”

Stall at Ballard Street Market in Seattle in 2014 – sense of place as a property of things and environments.

Genius loci or spirit of place is derived from the belief that particular places have their own spirits or gods. It was a common notion in the 18th and 19th centuries, referred to, for instance, by Alexander Pope and John Dryden. D.H. Lawrence wrote in 1918 that: “All art partakes of the Spirit of Place in which it is produced.” This expression seems to have declined in usage, perhaps as the world became increasingly disenchanted in the 20th century, and is being pushed aside by the less sacred term “sense of place.”

Jackson is right that this is an awkward and ambiguous expression because it attributes “sense” – a human and animal faculty – to unfeeling bits of geography.

Sense and Nonsense of Place

Landscape architect Grady Clay was even more outspoken when he wrote about “sense and nonsense of place.” He suggested that ‘sense of place’ is “a sociological invention” and he concocted a table of “Buzzwords for the manufacture of a ‘Sense of Place’ found in contemporary real-estate advertisements”: for example

- Luxurious waterfront estate mint-condition

Spacious prestigious location close-to

Elegant English landmark historic ambience

Stately Classic enclave panoramic vista

There is no undoing the development of language, but I do think using it as a naive substitution for spirit of place is unfortunate and best avoided.

Sense of Place as a faculty for distinguishing and appreciating places

This is the most common usage. It refers to a human faculty that pulls together and arranges information from the senses of sight, smell, touch, hearing, and also calls on memory and imagination. It is a living ecological relationship between a person and particular place, a feeling of comfort and security, similar to what environmental psychologists consider place attachment. Ian Nairn, for example, has written: “It seems a commonplace that almost everyone is born with the need for identification with their surroundings and a relationship to them. So sense of place is not a fine art extra, it is something we cannot afford to do without.”

From a broader perspective sense of place is an element of most social and cultural experiences. It is what Erskine Caldwell was driving at when he declared that there would be “nothing to write about if people had no fixed places of living.” In a cultural context sense of place is usually shared by others living in the same bit of the world and is an essential part of regional and local enthusiasms.

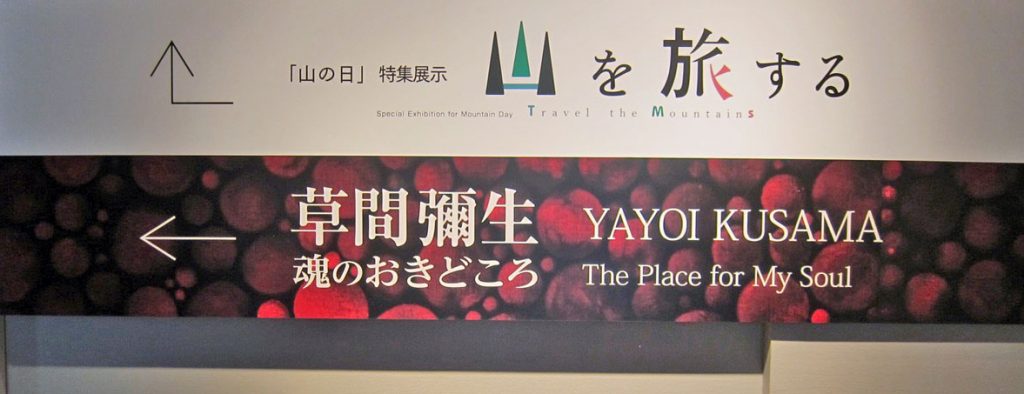

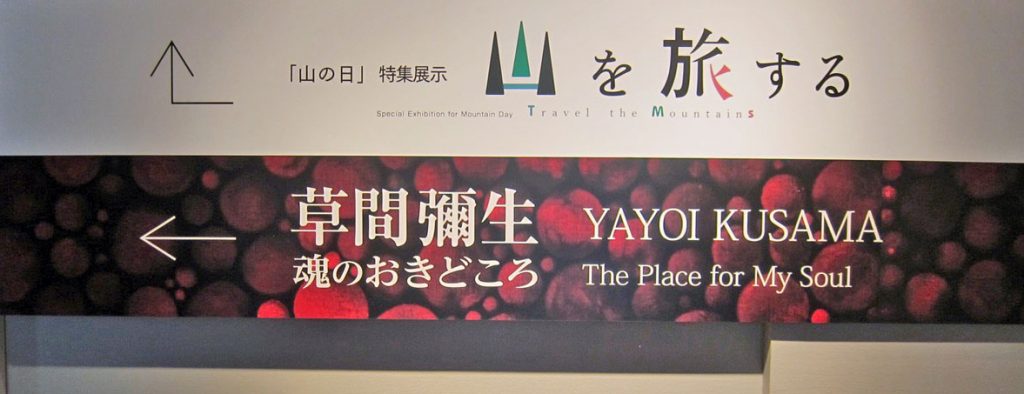

An Exhibition of Works by the Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama in the art gallery in Matsumoto, the city where she grew up

Two installations by Yayoi outside the Matsumoto Gallery – in her distinctive polka dot stye

It is, furthermore, an intersubjective feeling,an innate faculty possessed in some degree by everyone and recognizable to others who live elsewhere. This was captured well in the Hawaiian Airlines inflight magazine for August 2014 which had an article on watershed reclamation projects on the Islands that are being used to restore traditional agriculture and ecosystems. Place in Hawaii is closely tied to watersheds and the article had this to say. “Hawaiians have a deeply anchored sense of place, of ‘my place’ and ‘your place.’ They take of their place, and respect your place, and know the difference.” This is not going backward but tapping into ancestral memory to promote ecological humility and responsibility.

But it is also a sense that can be enhanced through critical attention to what makes places distinctive, how they have changed and how they might be changed. As a critical approach to an appreciation of the distinctive personalities of different environments, the critical enhancement of sense of place is an aspect of education in Geography, Architecture, Landscape Architecture, and Urban Design.

Variations in Sense of Place over Time

Sense of place is constant neither over the course of individual lifetimes nor over the course of history. For young children geographical experience is constrained, mostly to house and immediate surroundings, so sense of place is tightly focused with few comparisons; for adults place experience are extensive, regional, even global, with numerous comparisons; for the elderly sense of place become increasingly constrained as mobility declines.

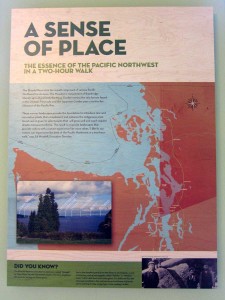

Poster at Bloedell Gardens in the Olympic Peninsula, 2014

Sense of place has varied over the course of history, especially as technologies of communications have changed. Tad Homer Dixon has noted that until about 1800 most people lived in rural areas, met only a few hundred people in their lifetimes and communicated by walking and talking. Indeed this was partly true of the area of South Wales where I grew up in the 1950s, and still applies to many parts of the world. Geographically focused lives lead to close and intense associations with places, not always pleasant but inescapable. With the advent of railways, the telegraph, radio,motor vehicles, air travel, and the Internet, sense of place has been spread-eagled across the world.

Joshua Meyerowitz’ book No Sense of Place discusses the impact of electronic communications and he suggests that: “Where one is, has less and less to do with what one knows and experiences.” Lives in the 21st century are increasingly multi-centred and transnational. Sense of place is now comparative rather than rooted.

Different Types of Sense of Place

John Eyles’ book Senses of Place (Silverbrook Press, Warrington, 1985) was an investigation of what people think of where they live, based on many interviews he conducted in the town of Towcester in the Midlands of England. The results allowed him to differentiate several different senses of place. The most important were:

- Social – dominated by social ties and interactions

- Apathetic or acquiescent – little interest in place

- Instrumental –place regarded either as a means to an end or as preventing opportunities

- Nostalgic – dominated by feelings about the past

Substantially less important were the following, which are usually treated in discussion of sense of place as essential:

My guess is that this ranking would not apply in other situations. For instance in the Cascadia region of North-West North America, where I now live, mountains, ocean and forest feature so prominently that the environment is fundamental to many people’s sense of place. But regardless of whether Eyles’ conclusions apply outside the town where he did his case study, his work is important because it shows that sense of place is not some sort of universally consistent response to the world.

Schmuel Shamai tried something similar to Eyles in the early 1990s. He argues that sense of place is something that can be measured. He subjected his questionnaire survey data of Jews in Toronto to various statistical tests that allowed him to identify seven levels of sense of place:

- not having a sense of place

- knowledge of being located in a place

- belonging to a place

- attachment to a place

- place devotion/allegiance

- involvement in a place

- sacrificing one’s life for a place

Drudgery, Oppression and A Poisoned Sense of Place

Place experiences can be negative as well as positive. For teenagers in a small town or women subjected to domestic violence a sense of place is about being trapped somewhere rather than belonging to it.

Escaping place. This movie (which I have not seen and about which I know nothing) has a title lifted from the 1965 song by Eric Burdon and The Animals (We gotta get out of this place, if it’s the last thing we ever do).

Sense of place can also contribute to exclusionary attitudes and practices. The psychologist Marc Fried, who in the 1970s wrote about uprooted communities in Boston, has more recently commented on “pathologies of community attachment” as disorders of place attachment. He suggests that they can be contagious, leading to territorial competition, warfare, even genocide.

I have written about these pathologies of place attachment as “a poisoned sense of place” in my essay on “Sense of Place” in Ten Geographical Ideas that Have Changed the World. This is the result when sense of place turns sour and becomes exclusionary. Much of what is positive in sense of place depends on a reasonable balance. At one extreme, when that balance is upset by an excess of placeless internationalism the local identity of places is eroded. At the other extreme, when that balance is upset by excessive commitment to place and local or national zeal, the result is a poisoned sense of place in which other places and people are treated with contempt. In its mildest forms this is apparent in nimbyism and gated communities. In its extreme forms, as Fried suggests, it is revealed ethnic nationalist supremacy and xenophobia. It was apparent, for example, in the place cocoons that Europeans took to protect themselves from the local contexts of their colonies that they found distasteful, thus bits of Britain were reproduced in India, and a Spanish way of life was exported to Latin America. At its most extreme it was manifested in Nazi Germany and the attempts at ethnic cleansing in Rwanda and in the former Yugoslavia, where obsessive love of national landscape and culture led to brutal attempts to purify the homeland by removing whatever and whomever was considered not to belong.

GIS and Measurement of Sense of Place

Agarwal has attempted to develop a computational theory for sense of place that will “enable the identification of minimal parameters for simulating sense of place in place-based models.” On the basis of 50 interviews she proposes that sense of place is a mechanism through which individual conceptualizations of place are grounded in a collective notion and develops a model for a “cognitive ‘sense of place’ as follows:

- SoPc can be expressed as < environmental knowledge : spatial familiarity : neighborhood : boundaries : k>, where k represents any symbolically important element that has been omitted within the constraints of the experiment. the meanings of place and its links in the real world. Sense of place is shown to be a representation of ontological commitments in the real world for the formation of a place.”

I am not sure what to make of this except to note that sense of place is topic that can be approached from many different angles and it is wise not to assume that the angle you or I prefer is the only one with some measure of legitimacy.

Global Sense of Place

Doreen Massey, a geographer, suggests that it is necessary to rethink places as particular moments in intersecting social and economic relations – in effect as nodes in open and porous networks that are global in their reach. She further argues that we need a progressive or global sense of place – a global sense of the local – which is adequate to an era of space-time compression. This understands each place as a focus of a distinct mixture of both wider and more local social relations, and which interact with the accumulated history of a place. This political economic view of places as nodes in systems of networks has been widely accepted in academic geography.

Sense of Place as a Phenomenological Bridge between Self and World

A reasonable and balanced sense of place connects person and environment; it is phenomenological bridge based in direct experiences of the world. Our senses respond to places and places are informed by how we sense them. This experiential connection is at the heart of Feld and Basso’s 1996 edited book Senses of Place. They are anthropologists interested in active processes of sensing places. Their aim is to move beyond “facile generalizations about places being culturally constructed” to an understanding of the ways in which places naturalize different worlds of sense. The essays in their book “…locate the intricate strengths and fragilities that connect places to social imagination and practice, to memory and desire, to dwelling and movement.” Basso’s own chapter on places in the Apache landscape is an account of how the Apache are alive to the world around them, and how places inform their comprehension of the world. Their experience of sensing places is both reciprocal and incorrigibly dynamic: “when places are actively sensed, the physical landscape becomes wedded to the landscape of the mind.”

Sense of Place as a Neurological Bridge between Self and World

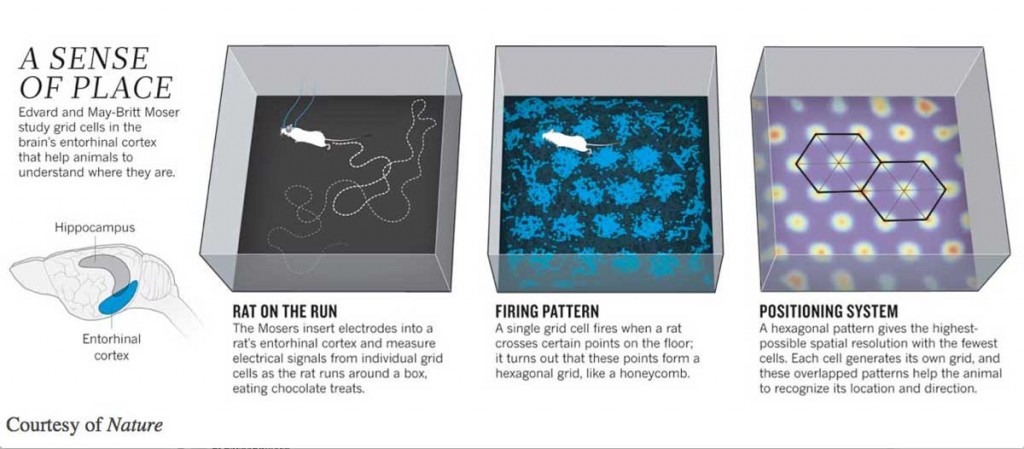

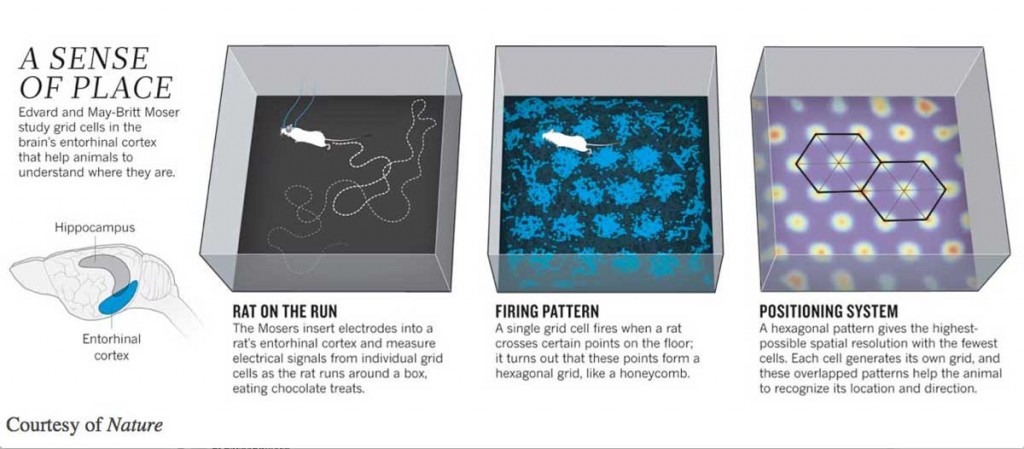

A similar notion of sense of place as a connection between person and world has begun to emerge in the work of neuroscientists who have identified “place cells” in the hippocampus that store memories of specific places, and “grid cells” that orchestrate these memories in ways that allow us to find our way around. Neuroscientists have been careful to point out that there is nothing like a map of places in the brain; instead experiences of places are actively organized in neural processes in our brains. It appears to be a failure of these processes that leads to dementia and Alzheimer’s and a person’s failure to find their way around. In other words, from a neurological perspective sense of place is simultaneously both in the world and in the brain. It requires a togetherness of environment and experience.

A diagram from Nature illustrating the neurological sense of place in rats developed by Edvard and Britt Moser (Nobel Prize winners 2014). Similar processes are known to happen in humans, and it is the failure of these that contributes to Alzheimer’s. What I think is significant is that this research has revealed processes that are simultaneously in the brain and in the environment.

A Pragmatic Sense of Place

There has always been a practical aspect to sense of place that translates it into buildings, landscapes and townscapes. It involves all means of planning, making, doing, maintaining, caring for, transforming, restoring and otherwise taking responsibility for how somewhere looks and functions. I have argued in several essays that the solutions to current challenges such as those of climate change, terrorism and inequality cannot lie with comprehensive, top-down, technical approaches alone. In addition to larger scale diplomatic and political answers it is necessary to have policies and practices that reflect locally distinctive conditions and meanings. These will require fostering a sense of place that blends an appreciation of local identity and difference with a grasp of widely shared processes and consequences, and then seeks locally appropriate local courses of action. I have referred to this as a pragmatic sense of place. It is necessary part, I think, of what will be needed to meet the multiple environmental and social challenges of the present century.

A Commercial/Retail Sense of Place

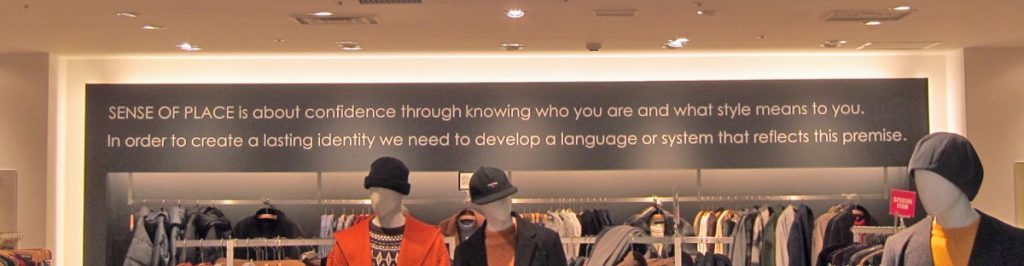

There is a Japanese retail clothing firm called Sense of Place/Urban Research that has borrowed the term as a marketing gimmick. This photo is of one of their stores that is located in the shopping mall underneath the Japan Rail station in Kyoto. The definition in the photo below, which says “Sense of Place is about confidence in knowing who you are” is on the wall above the mannequins. It illustrates clearly that the term sense of place has here been expropriated to mean personal style.

There is a Japanese retail clothing firm called Sense of Place/Urban Research that has borrowed the term as a marketing gimmick. This photo is of one of their stores that is located in the shopping mall underneath the Japan Rail station in Kyoto. The definition in the photo below, which says “Sense of Place is about confidence in knowing who you are” is on the wall above the mannequins. It illustrates clearly that the term sense of place has here been expropriated to mean personal style.

References

Agarwal, Pragya 2005 “Operationalizing ‘Sense of Place’ as a cognitive operator for semiotics in place-based ontologies” in A.G. Cohn and D,M. Mark (eds) Spatial Information Theory (Berlin: Springer-Verlag).

Clay, G.1994 Real Places: An Unconventional Guide to America’s Generic Landscapes, (Chicago: University of Chicago Press)

Eyles, John 1985 Senses of Place (Warrington: Silverbrook Press)

Feld. S and Basso K. H. (eds) 1996 Senses of Place (Santa Fe: School of American Research Press)

Fried, Marc 2000 “Continuities and Discontinuities of Place” Journal of Environmental Psychology, 20, 193-205

Fulford, R and Sewell J (n.d but about 1971) A Sense of Time and Place (Toronto: City Pamphlets)

Jackson J.B. 1994 A sense of place, a sense of time, (New Haven: Yale UP)

Massey D 1994 Space, Place and Gender (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press)

Meyerowitz, Joshua, 1985 No Sense of Place: The Impact of Electronic Media on Social Behaviour (London: Oxford UP)

Relph, E. 1997 “Sense of Place” in Ten Geographical Ideas that Have Changed the World, ed Susan Hanson, Rutgers University Press

Relph, Edward, 2007 “Spirit of Place and Sense of Place in Virtual Realities”, in Champion, E. (ed) Techne: special edition on Real and Virtual Places, 32-48

Relph, Edward, 2008 “Coping with Social and Environmental Challenges through a Pragmatic Approach to Place” in Eyles, J. and Williams, A., (eds) Sense of Place, Health, And Quality of Life (Aldershot: Ashgate)

Relph, Edward 2008 “A Pragmatic Sense of Place” in Vanclay, F., Higgins, M., and Blackshaw, A., (eds) Making Sense of Place: Exploring concepts and expressions of place through different senses and lenses (Canberra: National Museum of Australia)

Shamai, Schmuel 1991 “Sense of Place: An Empirical Measurement” Geoforum, Vol 22, No 3, pp. 347-358

Some other Sense of Place books not mentioned in this post:

Harwell, Karen and Reynolds, Joanna, 2006 Exploring a Sense of Place: How to Create your own local program for reconnecting with nature

Heise, Ursula K., 2008 Sense of Place and Sense of Planet: The Environmental Imagination of the Global

Gussow, Alan and Wilbur, Richard 1997 A Sense of Place: The Artist and the American Land

Steele, Fritz 1981 The Sense of Place

Stegner, Wallace, 1989 A Sense of Place

There is a Japanese retail clothing firm called Sense of Place/Urban Research that has borrowed the term as a marketing gimmick. This photo is of one of their stores that is located in the shopping mall underneath the Japan Rail station in Kyoto. The definition in the photo below, which says “Sense of Place is about confidence in knowing who you are” is on the wall above the mannequins. It illustrates clearly that the term sense of place has here been expropriated to mean personal style.

There is a Japanese retail clothing firm called Sense of Place/Urban Research that has borrowed the term as a marketing gimmick. This photo is of one of their stores that is located in the shopping mall underneath the Japan Rail station in Kyoto. The definition in the photo below, which says “Sense of Place is about confidence in knowing who you are” is on the wall above the mannequins. It illustrates clearly that the term sense of place has here been expropriated to mean personal style.