This post introduces a series in which I consider how places and experiences of place have changed in the past, and how they may change in the future.

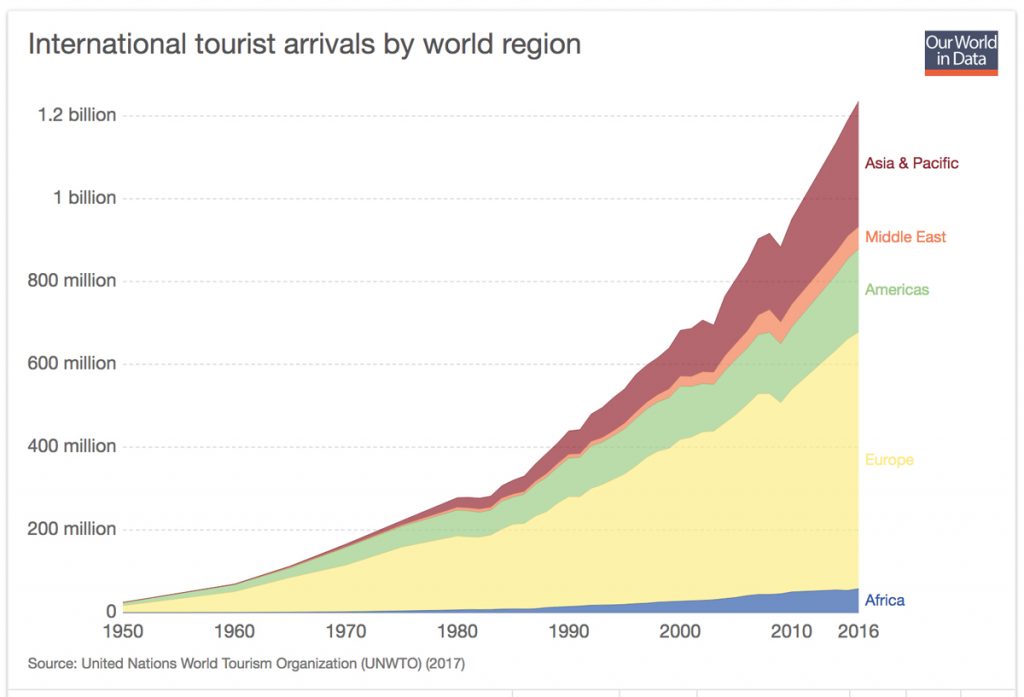

Current trends in population, climate and environmental change, electronic communications, social and economic inequalities, migration, urbanization, and international travel, could combine in the near future to have profound affects on place. While these trends are global in their scope, their consequences will probably play out in the neighbourhoods, villages, towns, cities and regions of everyday life. In this sequence of posts I want to try to project how places might change in the next thirty or so years in the context of these trends. And to do this a way that is well grounded, it is, I think, necessary to have some understanding of the history of places.

This introductory post outlines some of the assumptions I have made, and the approach I will follow. The next posts will offer an overview of how places have changed over the course of human history, and an examination of the role of continuity in place identities or what has not changed. Continuity matters because much of what exists now in places will continue to exist in the future, regardless of any technological or social revolutions. The series ends with a consideration of current trends, and prognoses for the future of places and place experiences.

The Fundamental Role of Place

“To exist in any way,” philosopher Ed Casey wrote in the foreword to his book The Fate of Place (p.ix), “is to be somewhere. Place is as requisite as the air we breathe, the ground on which we stand, the bodies we have…We are surrounded by places. We walk over and through them. We live in places, relate to others in them, die in them.” This expresses concisely the fundamental significance of place and the fact that it is through places that we know much of the world. It follows that it is important to understand something about how places have changed in the past and might change in the future.

In these posts I draw a distinction between “place” and “places.” Obviously, as the quote from Casey indicates, these terms are closely related (simply put, place is about places), but “place” by itself it is a relatively abstract and elusive concept that is difficult to define precisely (see my first post in this blog, which notes at least 29 different definitions). To mitigate this uncertainty I ground my approach as much as possible in consideration of the identities of “places,” the ones we walk over and through and live in. Some of these places are our homes, or locations where we have had formative experiences that are significant only to us. In these posts, however, my interest is about places at the geographical scales of neighbourhoods, cities, villages, sites, and regions, and the social processes that govern how these are made and experienced.

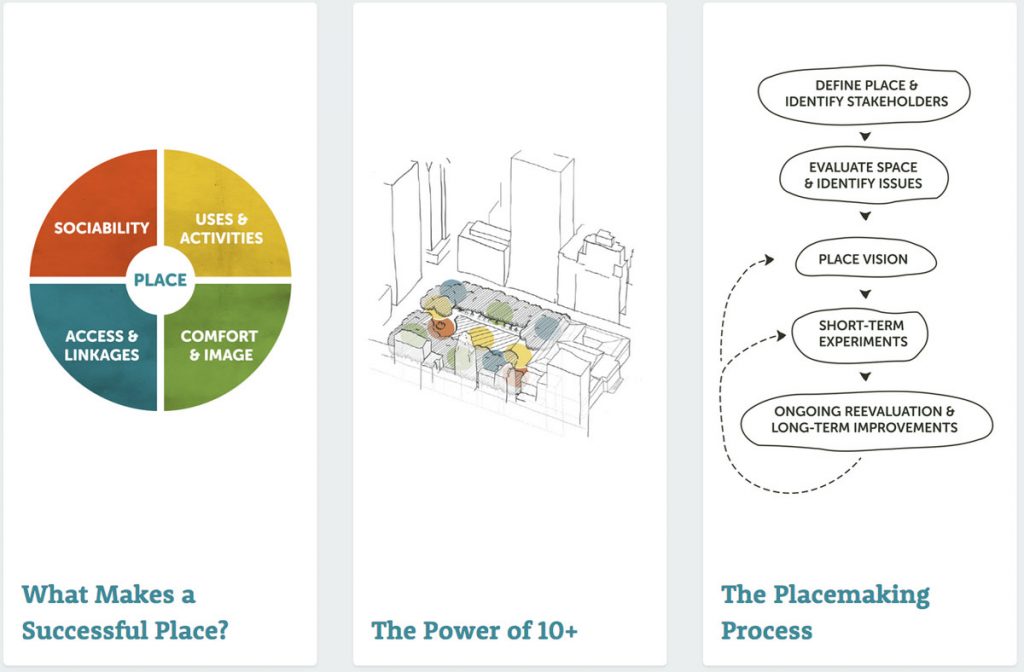

I have discussed the future of place in two previous posts . One summarized ideas expressed in a conference about ways to advance placemaking. The other outlined what I call a “pragmatic sense of place.” Those posts advocate the need to bring ideas of place and placemaking into the foreground of policy and planning. In contrast, here my emphasis is on the identities of material places, the ways they have been made, are being made, and might be made in the near future.

By material places I mean nothing mysterious. They are what we encounter whenever we go outside, whether into a village, a park, or an urban neighbourhood. They are the sites, districts, towns and cities we visit, and the regions we know because we have travelled across them. Material places are lived in and known through direct experiences, they have names and are filled with buildings, streets, landscapes, and activities, they are permeated by memories, values and beliefs that lend meaning to them. It was in material places that all historical events occurred, and it will be in them that the consequences of climate change, electronic media, inequality and migration will play out over the next few decades.

Although several of these posts are devoted to the history of places, my goal is to offer prognoses about the future of places. At the outside I acknowledge that this is an uncertain exercise. Some trends affecting them, such as demographic change, can be predicted with a modest degree of accuracy; but others such as technological innovations and their implications are very difficult to anticipate. One way to reduce some of this uncertainty is to attend to the history of places because this can indicate the types of processes and influences that have affected places in the past, and might reasonably be expected to do so in the future.

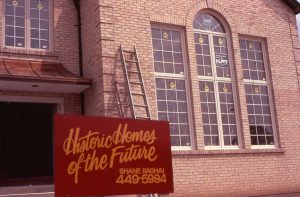

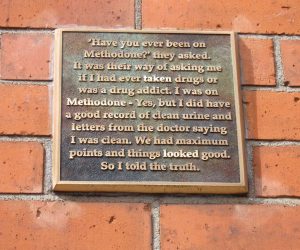

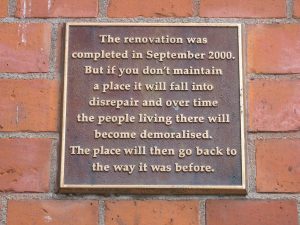

A construction site sign at Union Station in Toronto in 2014 provides a cautionary tale about projecting the future of place. Tomorrow was not a better place for Carillion, a multinational British construction company considered too big to be allowed to fail. Yet when it became hugely overextended the British government refused to bail it out and in 2018 Carillion was liquidated. Nevertheless, the material places Carillion constructed, such as the renovation to Union Station, do continue to exist.

An Approach to Understanding Change in Places

It is clear to me that any attempt to indicate how places could change in the future benefits from knowledge about how they have changed in the past. Therefore my approach begins with a survey of the history of places over the course of human history from 10,000 BCE to the present. As far as I know nobody has attempted anything like this (in The Fate of Place, from which I quoted above, Ed Casey does trace the the ups and downs of the concept of place over the last 2500 years but doesn’t say much about actual places). Of course, a brief account of the history of places over such a long time span is superficial, and cannot do justice to the differences between circumstances in previous ages and those of the present. Nevertheless it does provide a comprehensive framework for beginning to understand how places have evolved since the first permanent settlements were made. It is a valuable foundation for interpreting how places are currently changing, and offers cautions for making prognoses about the future of places.

A consideration of the history of material places is an exercise in thinking about change at social and geographical scales. I have taken as a guide for doing this the approach of the French historian Fernand Braudel, and I have adapted it to my specific purposes.

Braudel interpreted history through three concurrent time scales: the longue durée in which things endure or change very slowly; conjunctures in which consistent values and practices prevail for several generations; and events, which are idiosyncratic, filled with fascinating details but have short-lived consequences. In effect these three concurrent scales of time correspond to what might be called long-term, mid-term and short-term changes that are always occurring everywhere.

Aspects of longue durée from the perspective of place are those for which change is so slow that it is scarcely perceptible, such as rivers, mountains and (until very recently) climate. But they also include underlying processes such as population growth and urban growth, which have continued for millennia and underlie all change in places. Beliefs, traditions, a sense of national or regional identity, and even some institutions such as universities, can also endure across centuries in spite of political, economic and technological changes.

Conjunctures correspond to phases of place identity that demonstrate a distinctive combination of built forms, values, political systems, and ways of life that last for several generations or centuries. Then they are replaced by another phase as a result of technological innovations, a shift in beliefs, migrations, or other altered circumstances. These phases are apparent in familiar historical periods, such as the Middle Ages or the Industrial Revolution. Within each conjuncture there is consistency in how places are made and in the character of the identities of those places. While shifts in ways of making places do occur within a conjuncture, these are incremental around a consistent and coherent core, for instance in the way that Gothic architecture was refined over several centuries while retaining its basic characteristics.

16th Century Church in Shropshire, England..

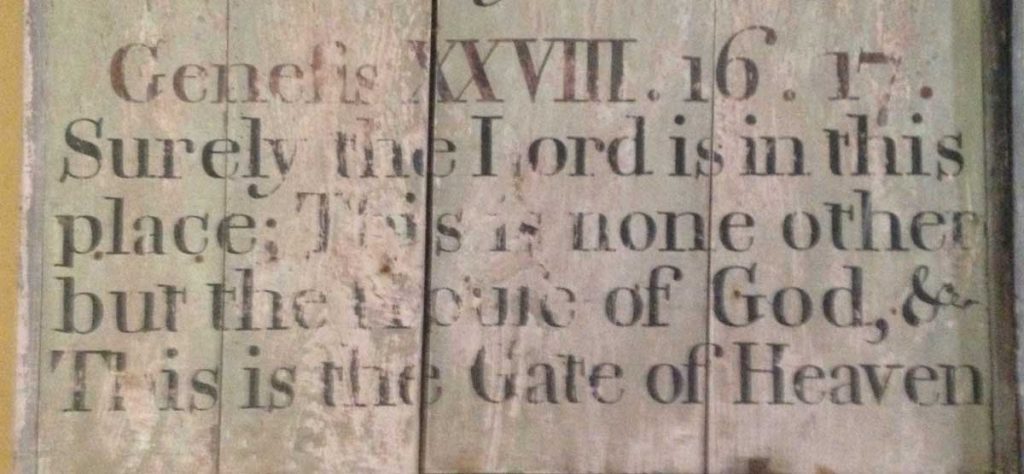

…and a text on the wall inside the church

Raul Hausman’s 1921 sculpture called “The Spirit of the Times”

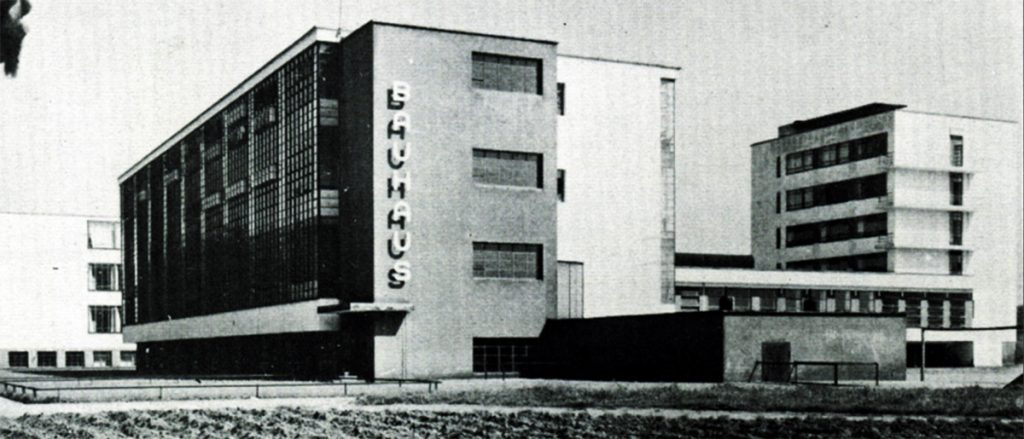

And a famous contemporary building – the Bauhaus

Indications of clear differences between place conjunctures – the Middle Ages and Modernity.

Extraordinary place events, for instance revolutions, destruction by wars, or natural disasters such as the great earthquake of Lisbon in 1775, are locally dramatic in the short-run, and sometimes serve as triggers that herald the emergence of a new conjuncture. However, Braudel notes that the apparent significance of events can be deceptive. Many have relatively little impact on wider and enduring characteristics of places and place experiences.

These ideas of longue durée, conjuncture and event provide a basis for contemplating the past and the future of places. I pay particular attention to the following:

• The identification of phases of place that lasted for several centuries or generations. I only consider short-term events if those appear to have had longer-term consequences. Because I am mostly interested in broad trends in place identities, I pay little attention to the longue durée role of physical geography, for instance, mountains as barriers and rivers as means of communication, which may have had significance for regional places. I do consider population and urban growth to be important long-term processes that have had major implications for places.

• The identities of places. By this I mean their plans, buildings and landscapes, and the ways they were made. There is material evidence of identities in archaeological sites, old buildings and fragments of old townscapes, and this provides a basis for distinguishing historical phases of places.

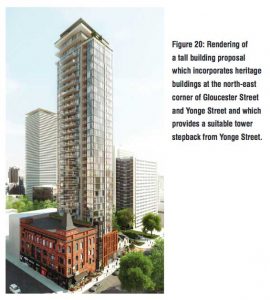

• For each phase of place I stress what is innovative in way of making places, whether because of new technologies or because of shifts in thinking. However, I recognize that continuity and persistence in the identities of places is no less important than change, and that what happened in each phase was always superimposed on whatever remained of earlier ages. In a sense this is a longue durée aspects of place, not unchanging but incrementally accumulating elements from the past. I will address this in a post about continuity. An important implication is that whatever exists now will be a foundation for the identities of places in the future.

• The history of places provides a basis for critical assessment of the implications of current trends in heritage and environmental protection, globalization, urbanization electronic media, increases in travel, and climate change. Are these manifestations of a shift from one conjuncture or phase of place experience to another (perhaps from a modern era to a postmodern, post-industrial one)? If this is the case, the result could be substantial changes in ways places are made and experienced in the near future.

• For most of the last 10,000 years the natural environment, including weather systems and ecosystems, could reasonably be considered as part of the longue durée background to everyday life, changing or being changed very slowly. With climate change, species extinction, and other profound anthropogenic impacts, these longue durée aspects of places could shift in unprecedented ways with radical implications for place experiences

References

Fernand Braudel 1949 The Mediterranean and the Mediterranean World in the Age of Philip II.

Fernand Braudel 1979 Civilization and Capitalism, 15th–18th Century

Ed Casey 1997 The Fate of Place: A philosophical history

This fragment of a streetscape in North York in Toronto is a mundane example of the unlikely juxtapositions of heterotopia. Roses New York offers a fusion of North American and Persian food, upstairs is an Egyptian psychic, next door a Korean-Japanese restaurant, the billboard advertises fictional places on Canadian TV.

This fragment of a streetscape in North York in Toronto is a mundane example of the unlikely juxtapositions of heterotopia. Roses New York offers a fusion of North American and Persian food, upstairs is an Egyptian psychic, next door a Korean-Japanese restaurant, the billboard advertises fictional places on Canadian TV.  The most intense example of heterotopia may be the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. The ruined building was remarkably left standing at the epicentre of the atom bomb explosion. It is a World Heritage Site that preserves destruction and reasserts the continuity of place, yet is also the place where rational knowledge reached beyond reason.

The most intense example of heterotopia may be the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. The ruined building was remarkably left standing at the epicentre of the atom bomb explosion. It is a World Heritage Site that preserves destruction and reasserts the continuity of place, yet is also the place where rational knowledge reached beyond reason.

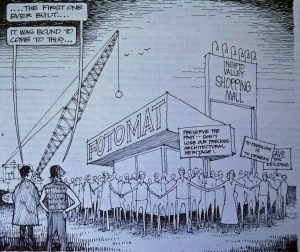

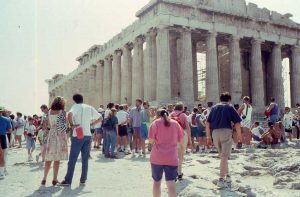

On the other hand mass tourism is a mixed blessing for those places that are on its receiving end, where sheer numbers are beginning to undermine the very place qualities that made them attractive. Venice is perhaps the most extreme example, where the dwindling resident population of about 55,000 is confronted annually by about 25 million visitors, many from cruise ships, but Barcelona, hiking trails in New Zealand and many World Heritage sites, such as the Pantheon in Rome, shown here in 2017, are confronting the same problem of authentic place qualities being eroded by sheer numbers of visitors.

On the other hand mass tourism is a mixed blessing for those places that are on its receiving end, where sheer numbers are beginning to undermine the very place qualities that made them attractive. Venice is perhaps the most extreme example, where the dwindling resident population of about 55,000 is confronted annually by about 25 million visitors, many from cruise ships, but Barcelona, hiking trails in New Zealand and many World Heritage sites, such as the Pantheon in Rome, shown here in 2017, are confronting the same problem of authentic place qualities being eroded by sheer numbers of visitors.

I fully endorse the quotation on the home page of Windfall from Scott Russell Sanders: “Many of the world abuses of land, forest, animals and communities have been carried out by people who root themselves in ideas rather than places.” This view is echoed in the themes to which each issue of Windfall is dedicated (and which are elaborated in informative Afterwords). These themes include commuter and in-between places, cemetery places, peak oil, global warming and the poetry of place, dwelling in place, and most recently the political poetry of place (which considers fake news). The poetry of place may be local and grounded, but that does not mean it cannot address broad social and environmental issues.

I fully endorse the quotation on the home page of Windfall from Scott Russell Sanders: “Many of the world abuses of land, forest, animals and communities have been carried out by people who root themselves in ideas rather than places.” This view is echoed in the themes to which each issue of Windfall is dedicated (and which are elaborated in informative Afterwords). These themes include commuter and in-between places, cemetery places, peak oil, global warming and the poetry of place, dwelling in place, and most recently the political poetry of place (which considers fake news). The poetry of place may be local and grounded, but that does not mean it cannot address broad social and environmental issues.

Toronto City Hall expresses municipal political power in its spectacular design of two curving towers embracing the council chamber (the disc object) hovering above a podium where the Mayor and councillors can stand for ceremonies, and its large public square, here being used for a celebration of the South Asian community. The photo on the right shows the view from the podium on a day when the square is not in use for an event. Compare this use of space with that of the bank towers in the financial district, shown below, which aim to maximize the economic value of the real estate they occupy by covering most of it with rectangular buildings on rectangular lots that aim to maximise the economic use of expensive real estate . The political power of place is often demonstrated by a rejection of the economic value of the land it occupies.

Toronto City Hall expresses municipal political power in its spectacular design of two curving towers embracing the council chamber (the disc object) hovering above a podium where the Mayor and councillors can stand for ceremonies, and its large public square, here being used for a celebration of the South Asian community. The photo on the right shows the view from the podium on a day when the square is not in use for an event. Compare this use of space with that of the bank towers in the financial district, shown below, which aim to maximize the economic value of the real estate they occupy by covering most of it with rectangular buildings on rectangular lots that aim to maximise the economic use of expensive real estate . The political power of place is often demonstrated by a rejection of the economic value of the land it occupies.

A sign in the City Hall of Mississauga, a suburban municipality on the west side of Toronto that is the sixth largest city in Canada, expresses its hope to participate in the global city network and to enhance its economic power of place while continuing to be “a place where people choose to be”.

A sign in the City Hall of Mississauga, a suburban municipality on the west side of Toronto that is the sixth largest city in Canada, expresses its hope to participate in the global city network and to enhance its economic power of place while continuing to be “a place where people choose to be”.

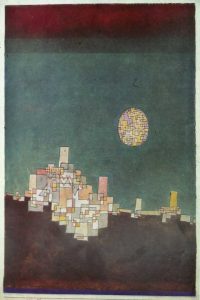

The intrinsic power of place is sometimes experienced by individuals as an affirmation of their religious convictions or as life changing epiphanies. In The Varieties of Religious Experience the philosopher William James (p. 71) quotes an account of someone’s experience on the summit of a high mountain: “I looked over a gashed and corrugated landscape extending to a long convex of ocean that ascended to the horizon…What I felt was a temporary loss of my identity that was accompanied by an illumination of deeper significance than I had previously attached to life. It is in this that I can say that I have enjoyed communion with God.” Paul Klee, the artist associated with the Bauhaus had a similar, though secular experience when he witnessed a moonrise over a town in North Africa just before World War One. It was a theme that recurred in his art for much of the rest of his life, such as this painting called “Chosen Site” from 1927.

The intrinsic power of place is sometimes experienced by individuals as an affirmation of their religious convictions or as life changing epiphanies. In The Varieties of Religious Experience the philosopher William James (p. 71) quotes an account of someone’s experience on the summit of a high mountain: “I looked over a gashed and corrugated landscape extending to a long convex of ocean that ascended to the horizon…What I felt was a temporary loss of my identity that was accompanied by an illumination of deeper significance than I had previously attached to life. It is in this that I can say that I have enjoyed communion with God.” Paul Klee, the artist associated with the Bauhaus had a similar, though secular experience when he witnessed a moonrise over a town in North Africa just before World War One. It was a theme that recurred in his art for much of the rest of his life, such as this painting called “Chosen Site” from 1927.

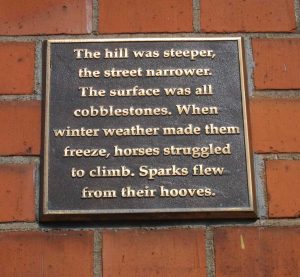

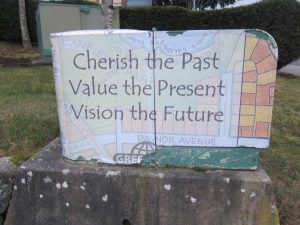

In his book What Time is This Place? Kevin Lynch investigates what he calls the “temporal collages” of superimposed pasts, present and future as they are manifest in built environments. He examines the diverse manifestations of time in cityscapes – clocks, parking signs, rhythms of movement such as rush hours, evidence of preservation and continuity in architecture, and various intimations of the future. His conclusion (p.241) is that: “…space and time, however conceived, are the great framework within which we order our experience. We live in time-places.” Time-places, he suggests, are consonant both with the structure of reality as we experience it, and with the nature of our minds and bodies. They are, in other words, manifestations of temporality.

In his book What Time is This Place? Kevin Lynch investigates what he calls the “temporal collages” of superimposed pasts, present and future as they are manifest in built environments. He examines the diverse manifestations of time in cityscapes – clocks, parking signs, rhythms of movement such as rush hours, evidence of preservation and continuity in architecture, and various intimations of the future. His conclusion (p.241) is that: “…space and time, however conceived, are the great framework within which we order our experience. We live in time-places.” Time-places, he suggests, are consonant both with the structure of reality as we experience it, and with the nature of our minds and bodies. They are, in other words, manifestations of temporality.

Heritage Town (the largest in America!) is a reproduction old-style Chinese food court on the second floor of Pacific Mall, a modern Asian shopping mall in Markham, in Toronto’s outer suburbs, in Canada. The photo on the right shows the tiled entrance gate underneath the exposed ducting of the modern building.

Heritage Town (the largest in America!) is a reproduction old-style Chinese food court on the second floor of Pacific Mall, a modern Asian shopping mall in Markham, in Toronto’s outer suburbs, in Canada. The photo on the right shows the tiled entrance gate underneath the exposed ducting of the modern building.