William James in The Varieties of Religious Experience, based on the lectures he gave in 1902, devoted an introductory chapter to “The Reality of the Unseen.” There are aspects of reality that are not experienced through the senses as we normally understand them, yet, as he argued in that chapter and subsequent chapters about healhy-mindedness, conversion, mysticism, they are undeniably real to those who experience them.

Thin places are sites where the reality of the unseen is experienced by individuals. They are, to repeat phrases that are frequently used to define them, places where heaven and earth seem only a few feet apart, where the veil between this world and the eternal world is stretched thin, places that allow a quiet shift in being, portals to another world that rejuvenates and heals. Thin places may or may not have buildings and distinctive topography. Their essential quality, their reality, is that they are felt, which is to say experienced through some other sense than sight, hearing, smell or touch.

The notion of thin places is frequently said by those who have written about it to have a long history, but the actual term appears to be quite recent, mostly used since the turn of this century. It is a valuable idea that coincides with phenomenological interpretations of place which aim to explicate place in all the ways in which it is sensed and experienced. This post is a cursory overview of what I have discovered about its origins and the diverse yet connected ways in which has been interpreted.

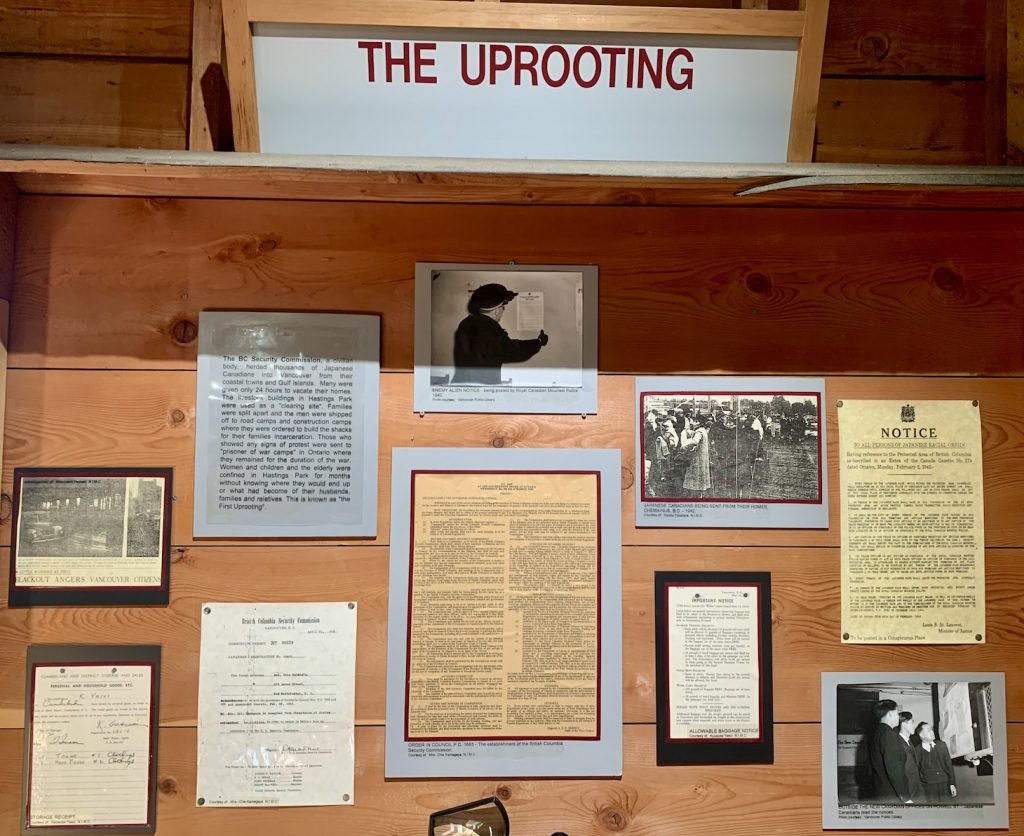

[I realise it is contradictory to have images in a post about unseen reality. I include them to suggest the variety of types of places where there could be some sort of quiet shift in being.]

Origins of the Idea of Thin Places – Christian, pre-Christian, Folklore

The idea of thin places is generally attributed to Ireland, or more generally to Celtic spirituality or Celtic Christianity. As far as I can gather, it was rarely used in publications before the twenty-first century. I have found one brief use of it in a 1946 publication by Evelyn Underhill to refer to Iona. Mark Roberts, a Biblical scholar, notes that he first heard the term about 1990 from a woman who was a devotee of Celtic spirituality. For devout Christians, who identify thin places in old churches or even accounts in the Bible, it is now associated with the earliest Christians who arrived in Ireland in 431 (St Patrick may have come in 432), and with the founding in 563 of a monastery at Iona (then considered part of Ireland and now part of Scotland) which quickly became a missionary base to convert the pagan populations of Ireland and Scotland.

Celtic spirituality is older than the arrival of Christianity. The numerous Neolithic monuments and burials sites in Scotland, Ireland, Wales and Cornwall are testament to this. Mindie Burgoyne, who organises tours of thin places, writes on her website: “The Pre-Christian and Celtic people of Ireland, Scotland, Wales and England had a keen sense for thin places. The landscape is littered with monuments, markings, and ruins that once boldly stated, ‘This is a thin place. This is holy ground’. The very ground itself seems to call out, ‘Come here and be transformed.'” Christian activities were often imposed on previous sacred sites. For instance, Croagh Patrick, the mountain in western Ireland where St Patrick is said to have fasted on the summit, where there has been a chapel since the fifth century, and which is now an important site of pilgrimage, is surrounded by Neolithic and bronze age monuments, some clearly oriented towards the mountain.

Martin Gray, in his book The Power of Place, suggests a possible reason for pre-Christian thin places: “Simply stated, many of the megalithic stone structures are situated at places with measurable geophysical anomalies (the so-called earth energies) such as localized magnetism, geothermal activity, specific minerals, and the presence of underground water. While there is nothing paranormal about these forces, what is fascinating is that ancient people located the specific sites where these energies were present.”

Kerri ni Dochartaigh’s 2022 book Thin Places, which was the stimulus for this post, is a remarkable autobiographical account of the healing power of places in the Celtic parts of Britain that she sought out as a way to recover from the deep distress of growing up in Derry in Northern Ireland during the civil war known as the Troubles. She says she first learnt of thin places from her grandfather, and her suggestion is that some sense of them has long been part of popular Irish folklore that has to do with fairies, leprechauns, and the Otherworld of gods and the dead. Nevertheless I can find no instance of its use in several books about Irish folklore (or, for that matter in histories of Celtic Christianity).

More probably it has been a term long used in everyday Irish speech to refer to places where you might feel the unseen reality of something otherworldly. It appears that in the last twenty-five years the idea of thin places has been borrowed from its Irish roots as a way to describe any site that somehow facilitates spiritual experiences, perhaps because they are where a miracle happened, a pilgrimage destination associated with a holy person, or, more informally, because they offer some awareness of the natural magic of the world.

Pilgrimages, Liminality and Placelessness

At least two organizations, Progressive Pilgrimages, led by pastors, and Mystical Tours, offer guided tours for small groups to thin places.

Progressive Pilgrimages notes that people participate in these for a variety of reasons, including seeking spiritual renewal, seeking a deeper understanding of their own spirituality, or perhaps simply looking for a sense of peace and calm in their lives. These probably apply to most pilgrimages to locations sanctified by some holy person or event, including the Haj and the Kumbh Mela, both of which attract millions of people. In effect, pilgrimages are journeys to a thin place that has been recognized and experienced by others for its spiritual significance and which therefore offers the possibility of an equivalent experience for oneself. The Camino de Compostela to Santiago, where St James the apostle is thought to be buried, has recently attracted almost half a million pilgrims a year. While only about 40 percent of those indicate on their registration forms that they are doing it for strictly religious reasons, the large numbers of participants in the Camino and in other pilgrimages show how widely valued are possible experiences of thin places, whether religious or not.

In their anthropological study of pilgrimages Vincent and Edith Turner describe the character of these experiences as “liminal”, which means they lie somewhere between everyday life and a world of different, deeper levels of existence (Turner 1978, p. 8, p.30). Though they had participated in the pilgrimage to Croagh Patrick, the Turners don’t refer to thin places. Indeed, they suggest that liminality is an experience of “a no-place and a no-time that resists classification” (Turner 1978, p. 250). This accords with the observation of the geographer Yi-Fu Tuan in his short book Religion: Place to Placelessness, that “in religion, placelessness is a precondition for – and a sign of – enlightenment” (Tuan 2012, p. 51). In Hinduism and Buddhism, enlightenment means that the limits of space and time vanish and the very idea of place as something human in scale vanishes (Tuan 2012, p. 38).

This may be so, but I think that if the Turners had been aware of the expression they might have preferred “thin place” to “no-place.” And Tuan might have accepted that thin places, including the destinations of pilgrimages such as Santiago de Compostela or Croagh Patrick, are best thought of as portals where material and spiritual worlds are adjacent and which open to the placelessness of enlightenment or Heaven.

Thin Places are Multicultural

Tuan’s comments about Hinduism and Buddhism are a reminder that while the idea of thin places may have Celtic origins, they are elements of all cultures and religions. Progressive Pilgrimages comments that the concept of thin places where people feel awe, wonder, and a sense of the divine, is found in many different cultures and traditions and is associated with churches, shrines, or natural landscapes.

Martin Gray’s suggestion that pre-Christian Celtic sites are often situated at thin places marked by geophysical anomalies or distinctive earth energies, has a strong family resemblance with feng-shui, the Chinese practice of harmonizing the vital energy, or chi, of the lands with the chi of human beings for the benefit of both. Temples, monasteries, dwellings, tombs, and seats of government were established at propitious places with an abundance of appropriate vital energy.

It appears that almost every culture has room for thin places marked by structures and events of currently practiced religions, whether cathedrals, temples, or humble shrines. A more subtle perspective that involves no structures or even names, is given by Kerri ní Dochartaigh, perhaps reflecting the important role of the types of thin places she experienced for herself: “The folklore of almost every culture holds room for these liminal spaces – those in-between places – those unnamable places, not to be found on any map” (Chapter Three).

The Character of Thin Places, and the role of Nature

Kerri ni Dochartaigh elaborates what she means by unnameable thin places. They are where we can more easily hear the land, the earth talking to us or where we are able to feel more freely our inner selves. “They do not have to be beautiful,” she writes (Chapter One), “or what might be described as wild, not just forests, mountains and coves”; they could be “a supermarket parking lot with just one tree, the back of housing estates where life has been left to exist.” They somehow make us feel larger than ourselves, held in a place between worlds, allowing for a pause in time, to see a way through.

Implicit in these comments is the acknowledgement that the experience of thin places depends perhaps as much on the sensitivity of individuals as on the character of the place. Just as some people have a heightened sense of smell or awareness of colour, so some are more open to appreciating the qualities of thin places.

Her descriptions of the thin places she experienced, the ones that helped her to overcome the enduring deep psychological stress resulting from a traumatic childhood on the front lines of violent civil war, where her home was fire-bombed, and a close friend was murdered, are all marked by encounters with the natural world, especially with birds and flying insects that know no borders. She attends to and cares for the fragments of the natural world she encounters. And it is these that seem to lead to experiences in which she finds she can stand outside the harsh realities of the material world.

Other recent commentaries about thin places mention the possible role of nature or natural landscapes, but with little elaboration. Nevertheless, I think this is an important connection that the Romantic poets and others (Thoreau, Ruskin, John Muir, Aldo Leopold) have often implied. William James (1961, pp. 69-71) gives several examples of individuals who experienced from the tops of mountains a rushing together of inner and the outer worlds, a feeling of the infinite, and a temporary loss of identity, accompanied by an illumination which revealed a deeper significance of life. Wordsworth captured this sense of a shift away from materiality in his poem composed a few miles above Tintern Abbey: he describes the “beauteous forms” of steep and lofty cliffs, hedgerows, pastoral farms, and then succinctly captures the profound emotional reaction these stimulated :

“To them I owed another gift…that blessed mood …

In which the heavy and weary weight

Of all this unintelligible world,

Is lightened…”

Similar experiences probably lie behind the commitments of many dedicated conservationists and, perhaps in more modest form, many of us who seek recreation in natural settings.

Secular Experiences of Thin Places

The idea of thin places is given a very broad interpretation by some of those who have written about it, effectively applying it to any moment of pleasure or insight that is derived from a place. Carrie Knowles, writing in Psychology Today compares them to “happy places” which provide an opportunity to step away, even for a moment, to refuel. More substantially Eric Weiner, a travel writer, acknowledges in a column he wrote in 2012 for the New York Times that the idea of thin places has origins in Irish folklore, but suggests that the term refers to all “places that beguile and inspire, sedate and stir, places where, for a few blissful moments I loosen my death grip on life, and can breathe again.” A thin place for him not necessarily a tranquil place, or a fun one, or even a beautiful one, but is part of the transformative magic of travel. To make his point he gives examples of thin places he has experienced, including St Patrick’s Cathedral in New York, Hong Kong airport, and a tiny bar in Shinjuku in Tokyo. His conclusion is that thin places offer glimpses not so much of heaven but of earth unencumbered, as it really is,.

Weiner also reinforces that experiences of thin places depend on the attitude of the person as much as the character of the place. To some extent thinness, like beauty, he suggests, is in the eye of the beholder, but there are steps you can take to increase the odds of an encounter with thinness, beginning with having no expectations and exploring the world with an open mind rather than a predetermined focus.

The Enigmatic Healing Power of Thin Places.

Clare Cooper Marcus, a professor and practitioner of landscape architecture, decided that as part of her recuperation after a life-threatening illness she should to go to Iona, the cradle of Celtic Christianity and widely regarded as a thin place, though she makes no mention of that. She writes of her initial experiences: “I am content to be in this place. It is a relief to be in a place where words are few but sounds are many… Perhaps on Iona I can find contentment in not-knowing, not-thinking. Perhaps I can just learn to be” (2010, p.34). And after spending many months there her conclusion is: “My soul is soothed…I cannot say why this particular place nurtures me as no other, what particular resonance draws me back. Yet I know this is my place of healing. That is enough” (2010, p.376).

Marcus returned from Iona to found a landscape architecture practice called ‘Healing Landscapes’, based on the idea that nature-oriented landscapes can promote recovery from stress via passive contact, which can be as simple as looking out of a window, or physical activity such as walking and sitting outside in a “healing garden”. Her commissions have included gardens for hospitals and long-term care facilities for patients with dementia. My sense is she has effectively turned her own experience of a thin place into designing potentially thin places for others to help them cope or heal.

This conclusion is appealing but perhaps too simplistic. Kerri ní Dochartaigh, in her explicit autobiographical consideration of the role thin places played in helping her recover from the psychological consequences of her traumatic childhood, is more cautious and complex about their capacity for healing. She concludes her book Thin Places (Chapter 13) enigmatically with the following remarks:

“The places we are from do not define us, they do not make us, they do not root us, they cannot hold this earth from its inescapable turning…

Places do not heal us, they do not take the suffering we have known and bury it in their bellies…

Places do not take away our sorrow.

Places only hold us, they only let us in. Places only hold us close enough that we can finally see ourselves reflected back.”

Bibliography

James, William 1961 (1902), The Varieties of Religious Experience, Collier Books: New York, especially Chapter 3 The Reality of the Unseen

Marcus, Clare Cooper, 2010 Iona Dreaming: The Healing Power of Place, Nicolas Hays Fort Worth Florida, 2010

Marcus, Clare Cooper, https://www.cultivatingplace.org/post/2017/09/21/the-therapeutic-power-of-the-garden-with-clare-cooper-marcus

McCann, Fiona 2021 “Earth Care and Recovery in Kerri Ní Docharthaigh’s Thin Places” Estudios Irlandeses, Issue 19, 2024, pp. 1-12. https://doi.org/10.24162/EI2024-12415

Ní Dochartaigh, Kerri, 2022, Thin Places: A Natural History of Healing and Home, Milkweed Editions (I read the e-version of this book, which is why I have not included chapter references rather than page numbers for quotes).

Roberts, Mark, 2012 Thin Places: A Biblical Investigation, accessed at

https://www.patheos.com/blogs/markdroberts/series/thin-places/

Tuan, Y-F. with Strawn M. (2012) Religion: From Place to Placelessness. The Center for American Places at Columbia College, Chicago.

Turner, V. and Turner, E. (1978) Image and Pilgrimage in Christian Culture. Columbia University Press: New York. (Second edition, 2011).

Underhill, E., 1946, Collected papers of Evelyn Underhill, Longmans, Green & Company, New York, NY.

Weiner, Eric, 2012 “Where Heaven and Earth Come Closer” New York Times, accessed at

https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/11/travel/thin-places-where-we-are-jolted-out-of-old-ways-of-seeing-the-world.html