This post is the second part of a history of places and is one in a series about the past and future of places. An initial post explained my overall aims, and noted that my emphasis is on material places rather than the more abstract notion of place. The first part of the history of places considered how places changed from about 10,000 BCE to 1000 CE, noted my criteria for identifying historical periods of places, and identified some qualifications about my approach, including the fact that population and urban growth have always been in the background of how places have been made.

Note that the brief history in these two posts is only intended to provide sufficient information to give a broad indication of the different ways places have been made and experienced over the course of human history. Rather than primary research, it draws on secondary and web sources, combined with my direct experiences of the remnants of places from particular historical periods (which I illustrate where I can with my own photos).

This post considers places in four distinct periods – the Middle Ages, the Age of Reason, the Industrial Century, and the Modern Era.

Religion and the Places of the Middle Ages

The Dark Ages between about 500 and 1,000 CE witnessed a disaggregation of places as towns and settlements that had been established throughout the Roman Empire declined or were abandoned in the absence of political coherence. From the 10th century some measure of stability began to be re-established as Christianity, which had developed as an organized religion in the last centuries of the Roman Empire and then slowly spread across Western Europe, was increasingly adopted by the rulers of regional kingdoms. With stability came the possibility of making places that might endure, and from the 11th to the 15th centuries Christianity dominated the character of how those places were made. Villages and towns were essentially built around churches or cathedrals, which were often magnificent structures with pointed arches, stained glass windows, ornate decorations, flying buttresses, and spires pointing heavenward. They were physical demonstrations of the narrative that religion and faith were the most important aspects of existence. Everyday life for everyone was permeated by religion, princes and peasants alike. It set the rhythms of the day, the week and the year; it was the foundation of education; nuns and monks ran hospitals and attended to the poor and destitute; everyone contributed in some way to the building of churches, if not with money then by providing their labour.

The cathedral city of Chartres demonstrates the main features of religious places of the Middle Ages. The cathedral at the centre (on the site of several previous cathedrals), was built about 1200, still dominates the skyline and is surrounded by narrow winding streets. (I took this photo in 1969)..

Similar place characteristics on a smaller scale at the village of Weobley in Herefordshire, England. The church at the centre of the village was built in the early 12th century. The timber frame buildings close to the church were built about 1500; those in the foreground are more recent, probably replacing older ones adjacent to the wide street which would have been the market place. (Photo was taken about 1970).

This was, however, also a time when kingdoms jostled for power and control of territory. Wherever there was a threat of attack by a marauding army places were built with security in mind – villages on hilltops that offered some degree of defence, towns surrounded by walls or protected by a castle. Perhaps this generated a sense of security in the thousands of small villages producing food, or perhaps technological improvements in water and wind mills were responsible, but whatever the reason there were increases in agricultural production that contributed to economic prosperity. This led to the development a trading network across much of Western Europe, especially for wool but also for tin, lead, wine and timber, and this trade generated the wealth necessary for constructing churches, and for making the places where those churches were located.

With economic growth came population growth, and in the 11th and 12th centuries the population of Europe doubled. Much of that growth was accommodated by rebuilding towns that had decayed during the Dark Ages or by constructing new towns. The former often had an organic maze of streets following routes of old tracks and paths; many of the new towns were roughly planned with a loose grid pattern of streets, a square or wide street for a market, and a castle wherever defence was a priority. In both cases streets would have been crowded with a variety of buildings, some substantial with workshops or stores at ground level and residences above, others little more than shacks, and all constructed of whatever materials were locally available – limestone, sandstone, timber frames filled with wattle. The result was that places, even if they were centrally planned, for instance as defensive settlements, were as diverse as the regions where they were located. This diversity has now come to be regarded as a major amenity, and many medieval places, with their picturesque combinations of church, castle, distinctive architecture, and a maze of streets most easily travelled on foot, have recently been pedestrianized and become popular tourist attractions.

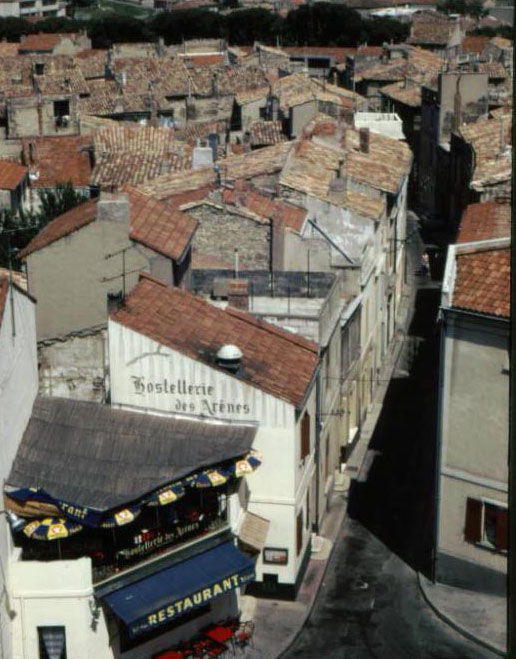

On the left the small town of Gordes in Provence, France, is an example of a medieval village on a hilltop site that provided some security from attack, with the church and a castle occupying the highest parts of the site. The buildings on the steep hillside illustrate the organic character of many medieval town plans, as do the winding, narrow streets of Arles, also in Provence, on the right.

Medieval place experiences were not entirely local. Although travel was dangerous and roads were little more than grassy, muddy tracks used by pack animals that could only be travelled on foot or horseback, clerics on official Church business and merchants on their own business regularly travelled between towns and different countries. A few million devout Christians took part in Crusades to Jerusalem, the central place of the Christian world. Many others made pilgrimages either to nearby shrines or to more distant ones such as Canterbury or Santiago de Compostela. In short, knowledge was shared throughout the places of the Christian world, including the principles for the layout of Gothic churches and abbeys, such as their orientation and the arrangements of altar, nave, choir, transept, and so on. Indeed the masons responsible for much of the construction of churches were itinerant, but they also had to adapt the standard design requirement to specific sites and to use mostly local building material because it was too difficult to move stuff around. This was done with remarkable skill, and the consequence was buildings that, although they shared the same standard elements, enhanced rather than diminished the identities of places.

Medieval understanding of the world and its places was, like towns and villages, structured around religion. This is the Hereford Mappa Mundi, made in 1300, and the largest medieval map known to exist. Jerusalem is in the centre because it was seen as the centre of the world in Christianity, with the British Isles bottom left the Mediterranean the centre bottom, the Red Sea top right, and the circumambient ocean on the outside.

In spite of the remarkable solidity and scale of medieval churches and castles (many of which have survived to the present day), there seems to have been a sense at the time that medieval places were just stepping stones to heaven, that religion was not a whole solution to life’s problems. This became especially apparent with the plagues of the 14th century, when the Black Death spread along trade routes and caused the death of more than 30 percent of the population of Europe. Neither faith, nor churches, nor castles were able to protect people and places from epidemics (nor, it seems in the covid-19 pandemic, can science and the efforts of centralised governments, though those should mitigate the relative scale of the consequences). Many villages were abandoned because almost everyone died, and in towns as well as the countryside the resulting shortage of labour weakened the authority of the Church. This was exacerbated by the fact that the secular ideas of classical Greece and Rome had begun to infiltrate medieval thinking in Western Europe. The character of medieval places began to shift. While religion remained important and great churches and cathedrals continued to be built for several centuries, trade and manufacturing began to play increasingly important roles in politics and daily life. Self-governing guilds of professional craftsmen formed in prosperous cities, market halls were constructed, some almost as large as cathedrals, and a sense of secular community and cooperation began to develop. A new phase of placemaking was emerging.

Well-ordered Places and Uprooting in the Age of Reason

“Tis all in peeces, all cohaerance gone” declared the poet John Donne at the end of the 16th century. I think he had suddenly become aware that the values of religious world in which he had grown up had lost their import. For places a new type of coherence, one based on reason rather than religion, had in fact been developing for some time. The writings of the Roman architect/engineer Vitruvius had been discovered in the mid-15th century, and since then newly made buildings and places had begun to take on a classical character. Churches in Italy, including St. Peter’s in Rome, were built with columns, pediments and domes similar to those of ancient Rome, and plans for towns, including the square in front of St. Peter’s, were given geometric regularity.

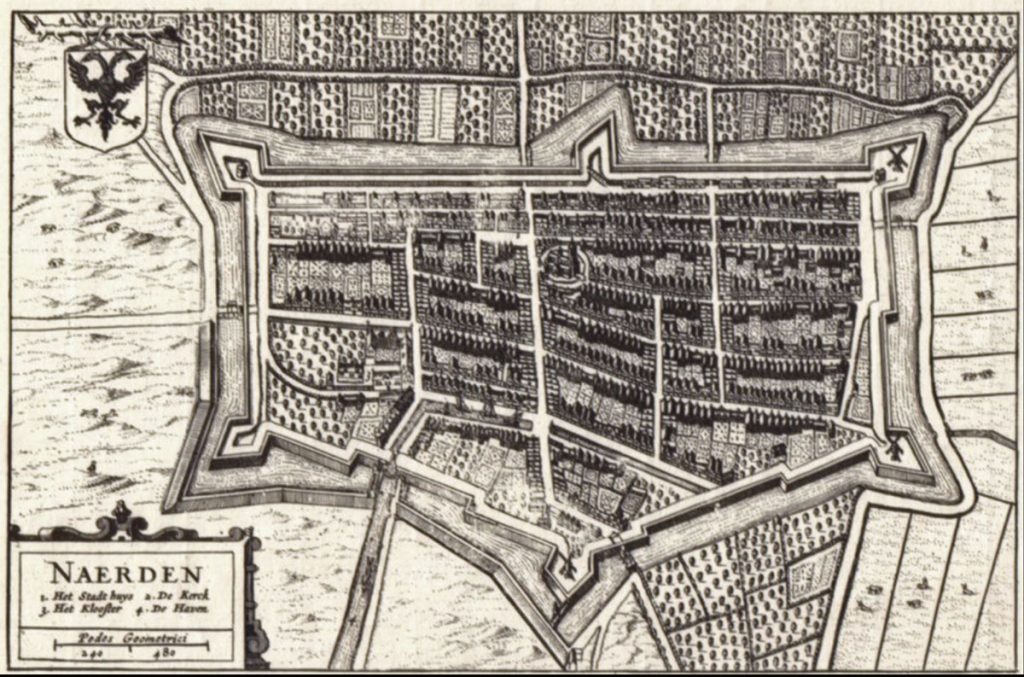

The merits of a rational approach to making places was made explicit by Rene Descartes in 1637 in Discourse on the Method, the foundational philosophical text for the Age of Reason. At the beginning of Part 2 he declares: “Old cities which, from being at first only villages, have become, in course of time, large towns, are usually ill laid out compared with the regularity of constructed towns which a professional architect has freely planned on an open plain.” He suggested that the “indiscriminate juxtaposition [of buildings]” and the “crookedness and irregularity of the streets” in old cities (i.e. those of the Middle Ages) must have been a matter of chance. However, towns planned by architects demonstrate “human will guided by reason.” He may have been thinking of entirely new towns that had to be fortified because they had a strategic role in defence and were built in elaborate geometric star patterns.

The star-fort of Naarden in the Netherlands, laid out in the 17th century was part of a ring of defensive settlements intended to protect Amsterdam. The promontories allowed cross-fire in the event of an attack. The orderly street pattern and rectangular fields outside the walls demonstrate Descartes’ ideal of planning according to “human will guided by reason.”

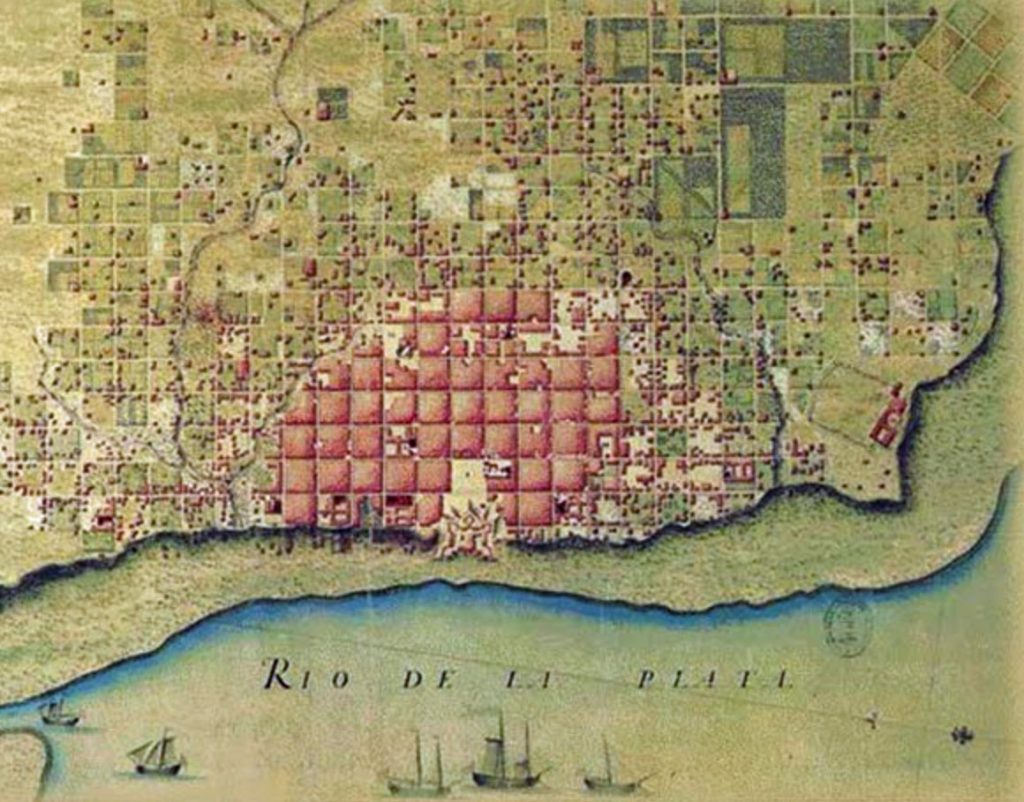

In fact, the shift to rational order in making places had been underway for more than a century partly because of the renaissance of classical ideas, and partly because the dissemination of these had been facilitated by the invention of the printing press in 1450. This promoted literacy, democratised education, and made it possible for new ideas to spread rapidly from place to place. Contemporary improvements in navigation ensured that some of these places were in distant colonies on recently discovered continents. Place names and cultural practices were transplanted, and, in perhaps the most notable indication of the placemaking preferences of the Age of Reason, so were the rational town plans that were coming into fashion. This was nowhere more clearly demonstrated than in Spanish Colonies. In 1513 King Ferdinand of Spain issued instructions for the expedition to the coast of Central America: “Let the city lots be regular from the start, so once they are marked out the town will appear well ordered as to the place which is left for a plaza, the site for the church, and the sequence of the streets; for in places newly established proper order can be given from the start.” These general guidelines were elaborated in minute detail in 1573 in Philip II’s Laws of the Indies for building new settlements. Their impact is still apparent in the regular townscapes of almost all the colonial settlements of Latin America.

The 1580 plan for Buenos Aires – a grid of squares with a central plaza where the church and government buildings were located. This geometric approach to planning colonial places was used throughout Latin America. Source: Patricia Sendin

From about 1550, as the theocracy of the Middle Ages waned, the growing power and wealth of kings and nobles came to be displayed in great palaces and country houses which left no doubt that these, not cathedrals, were now the places where real authority resided. Their architecture was often in the classical revival styles of the Renaissance, and they were surrounded by geometrically arranged landscape gardens, incorporating sophisticated topiaty, lakes and fountains that revealed the strength of human reason in bending nature to its will.

The great and wealthy places of the Age of Reason were not cathedrals but palaces surrounded by manicured landscape gardens, This is Vaux le Vicomte, built around 1660 south- east of Paris for Nicolas Fouquet, the superintendent of finances for King Louis XIV.

Wherever towns were created, such as St Petersburg in Russia, or remade, such as Lisbon after the earthquake of 1755, or added to, such as the New Town in Edinburgh in the late 18th century, they were laid out in the rational manner, guided by human reason. In the countryside the irregular strips and furrows of feudal agriculture were remade into angular fields more suited to more efficient agricultural practices. The Age of Reason imposed order on the landscape.

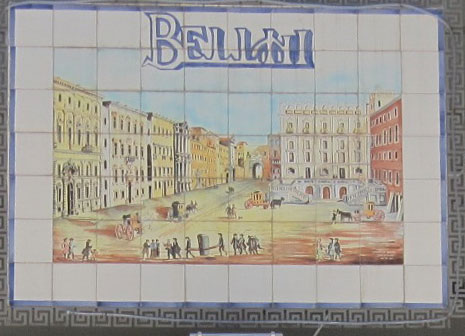

A wall plaque in Piazza Bellini in Naples with a rendering of the well-proportioned urban environment that was the ideal for making urban places of the Age of Reason – townhouses next to the street, windows in neat rows, smaller at the top, neat cornice lines, all arranged around an urban square.

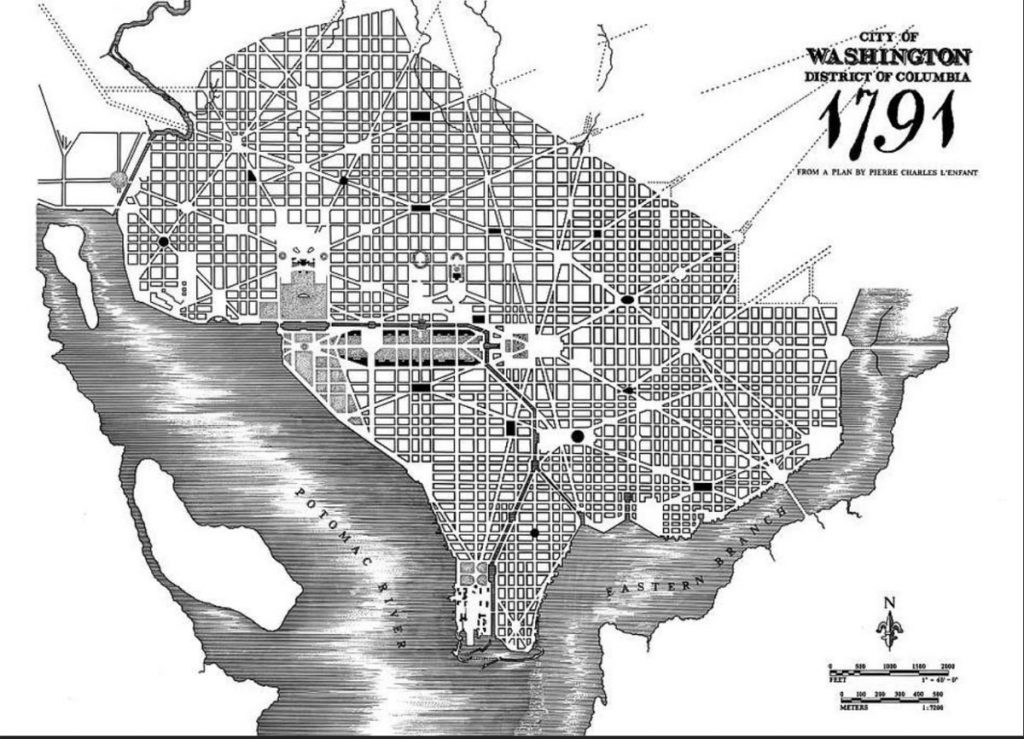

The apex of this redesign of the world came at the end of the 18th century in the newly created United States of America, where orthogonal surveys were adopted as the basis for preparing much of the new nation for settlement. Rectangular patterns were imposed on countryside and towns alike. In that same spirit, the new government commissioned a plan from the French-born American architect Pierre Charles L’Enfant for the capital city of Washington D.C., a plan that celebrated the rational principles of democratic government, with a great avenue (the Mall) leading to the Capitol, and other, slightly less grand avenues leading to the White House and cutting across much of the the rest of the city.

L’Enfant’s 1791 plan for Washington D.C., is the culmination of the ideals of town planning and placemaking in the Age of Reason, a background grid of streets, with diagonals superimposed, and the mall and grand avenues leading to the Capitol and the White House. In fact, the mall was used for railroads in the 19th century and the plan was not fully implemented until the end of the 19th century.

However, places in the Age of Reason were not all order and reason. The Enlightenment cast some dark shadows. The historian Fernand Braudel described the great capital cities of the time as “urban monstrosities… machines for creating both civilization and misery.” He was thinking of Paris, which by the mid-18th century had grown to 600,000 people, and London which had 750,000. While these both had new districts of elegant streets with circles and squares lined with well-proportioned dwellings, they also had neighbourhoods of great poverty, often where medieval bits of cities remained, and where, as William Hogarth’s contemporary engravings of Beer Street and Gin Lane show, people survived in crowded squalor and dulled their misery with wine or gin.

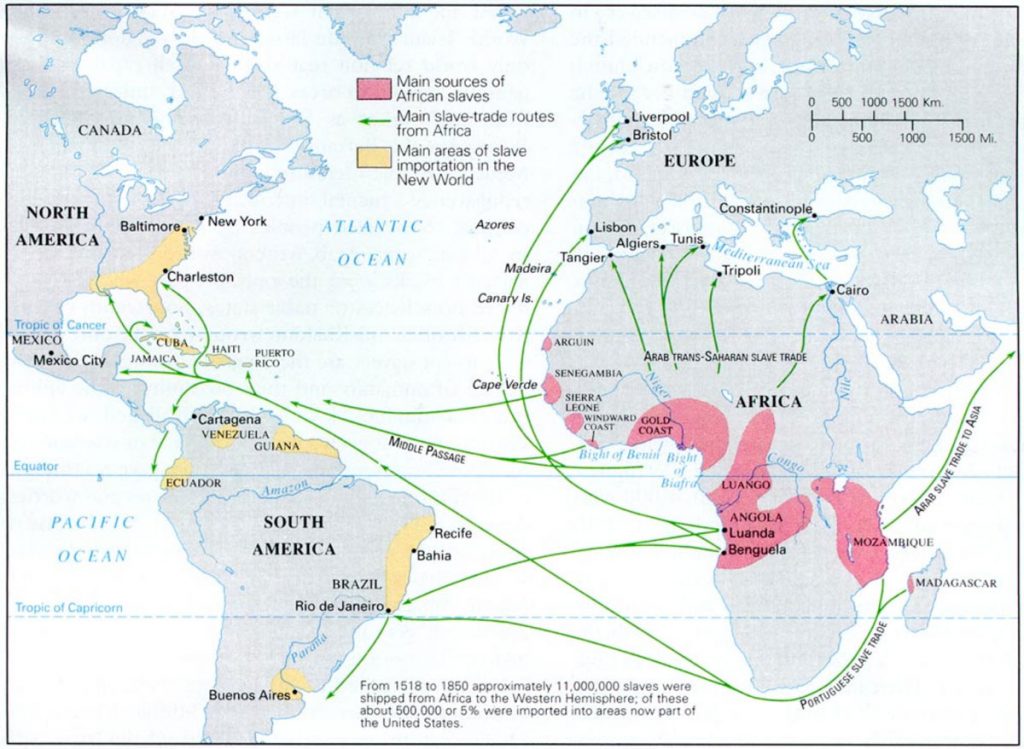

Furthermore, the Age of Reason was no exception to the fact that the creation of new places, no matter how reasonable, inevitably involves the destruction of existing places. The great palaces and country homes with their landscapes gardens often required the displacement of entire villages. On a far larger scale the massive placemaking aspects of colonialism were counterbalanced by equally huge place unmaking as indigenous peoples were pushed aside and devastated by imported diseases. Most dramatically of all, about 13 million Africans were uprooted from their homes and transplanted to other continents and unfamiliar places – 4 million to Brazil, 2.5 million to Spanish colonies, 2 million to British colonies of the West Indies and North America. The history of place is about uprooting and destruction no less than the making of places.

Places in the Industrial Century

The orderly practices of the Age of Reason for making places trickled on into the early 19th century in urban developments of elegant Georgian houses and in orthogonal surveys to prepare territories for settlement. However, their impetus had begun to wane before the end of the 18th century as innovations in manufacturing, such as the spinning jenny for cotton weaving and steam engines, heralded the onset of the Industrial Revolution and entirely different, utilitarian approaches to making places that prevailed until 1900 and lingered well into the 20th century.

The impact of this industrial shift outweighed all previous changes in placemaking. Indeed it effectively made all previous places appear obsolete. In 1800 at the beginning of the Industrial Century, city streets and farms still had much in common will all the places that had been made in previous ages – whether the Middle Ages or Ancient Rome and Greece – buildings were assembled by hand, on sites prepared by hand, most people still walked everywhere, houses were lit with candles, noises and smells were of animals and people. A hundred years later smells and noises were of machines which did much of the work, including making mass-produced possessions, buildings were coated in coal dust, hills were levelled with steam-shovels, people rode in streetcars or railways, streets had electric lights and were draped with telephone wires. The industrial age changed places in ways that that were utterly unprecedented.

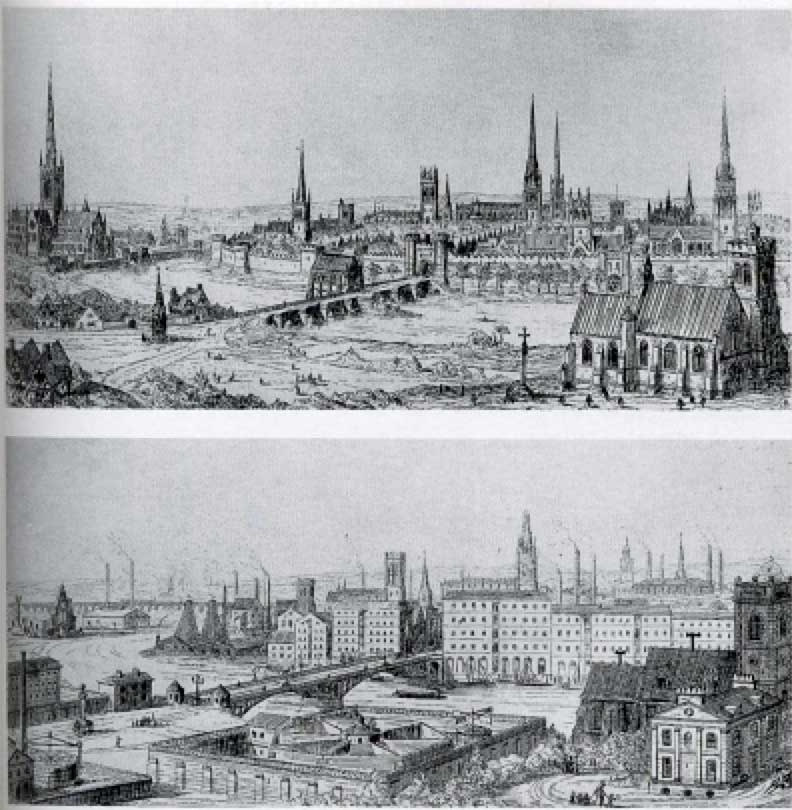

A drawing from Augustus Pugin’s book Contrasts, published in 1835, comparing ‘the noble edifices of the 14th and 15th centuries and similar buildings of the present day.‘ A skyline of churches and spires replaced by massive factories and their chimneys.

In the background of these changes was a dramatic acceleration rate of population growth, with its inevitable consequence of more people in more and larger places. The population in Europe doubled between 1800 and 1900 (numbers are not precisely known, but from about 152 million to 296 million); the population of England, the hearth of the Industrial Revolution, quadrupled, from 7.8 million to 30 million. Even though industrialisation caused serious pollution and, for some, grinding poverty, the main reason for this growth was reduced mortality – fewer children were dying and people were living longer, probably because of improved diets. It helped that a large share of the growth was accommodated by emigration to the great spaces of Australia, New Zealand, South Africa and particularly North America, where the United States grew from 5.3 million to 76.2 million between 1800 and 1900, at least 30 million of them immigrants. Many of those immigrants had come from rural regions with failing economies who had chosen to uproot themselves to seek a better life. In the new world the result was placemaking that spread across continents as settlers put down new roots. In the process, of course, indigenous populations were displaced, so this was also a time of great place unmaking.

Population growth in both the old world and the new was concentrated in towns and cities where factories provided relatively unskilled jobs paying wages which afforded a quality of life that, in spite of the pollution and slums, was often better than that of a rural labourer. In the United States in 1800 only 6 percent of the population was urban, by 1900 it was 40 percent; in England in 1800 about 33 percent was urban, in 1900 it was 77 percent. The rates of growth in individual towns and cities was dramatic. Bolton, a centre of innovation in cotton manufacturing in England, grew from 12,500 to 168,000 over the course of the century. London grew from about 1million to 5 million. Chicago grew from 5,000 in 1840 to 1.7 million in 1900. The character of urban places was remade, not least because so much of them was new and on a huge scale.

This area of Chicago that was developed at the end of the 19th century is an example of the scale and uniformity of urban expansion in the industrial age

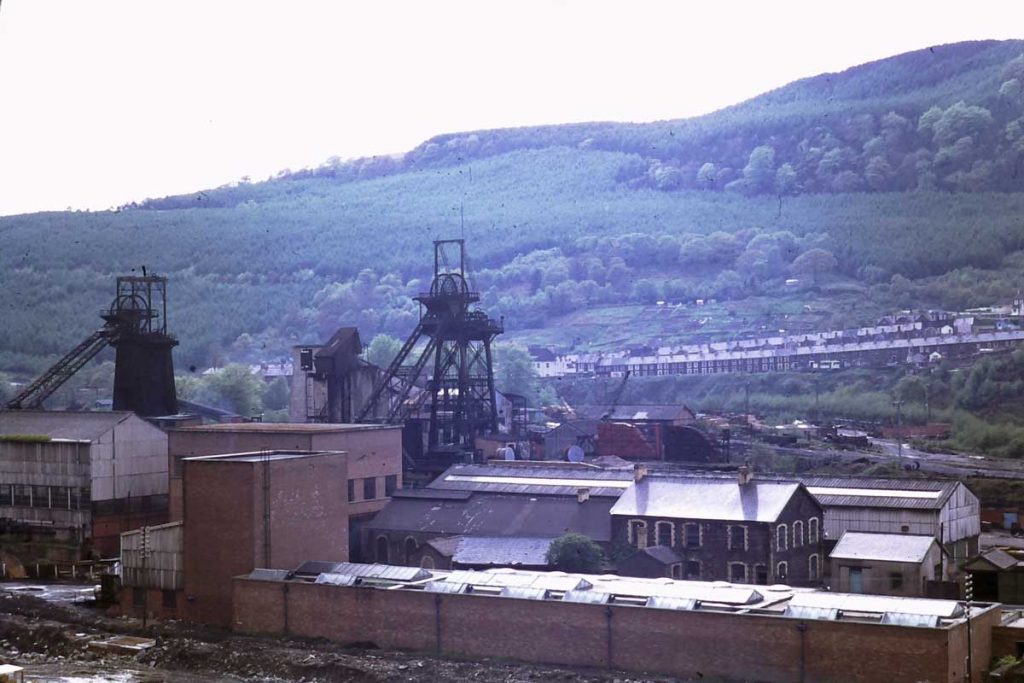

A coal mine in Treorchi in South Wales about 1975, with rows of houses for miners in the background. Except for the trees, which would have been stripped away, this place was much as it would have been a century before. However, the mines were closed about a decade after I took this photo and many signs of mining have disappeared.

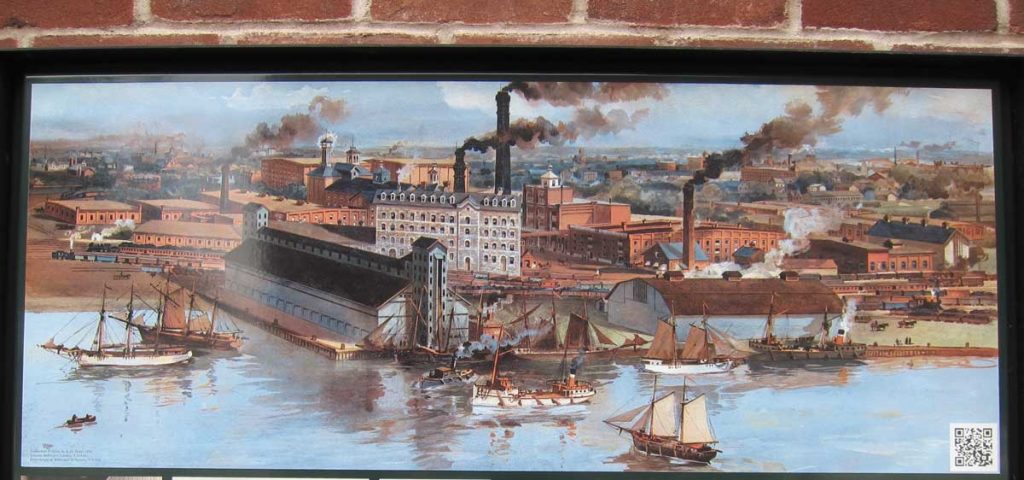

Almost everything about industrial cities was unprecedented. Factories with endlessly repetitive work done in shifts were themselves new types of workplaces; huge foundries; steam driven machines; iron bridges; skyscrapers with steel frames. Tenements and row houses, more or less mass-produced to minimal standards, were new types of placeless living places. Railways provided ways of travelling at speeds hitherto considered inconceivable. And because factories and railways were voracious consumers of iron and coal or wood, the provision of these required new types of places – towns entirely devoted to a single purpose, mining towns coated in coal dust and surrounded by spoil tips, factory towns choking in smoke; a rhythm of life dictated by the demands of production and shift work. Factories, not palaces or cathedrals were the great new buildings of the industrial age, widely illustrated in engravings and birds-eye view of particular places with smoke streaming from their chimneys as symbols of progress and the power of steam. Less illustrated but scarcely less substantial were legislatures, parliament buildings and town halls, usually large and elaborate buildings prominently situated in park-like spaces. They served as a demonstration that governments of liberal democracy, whether at a municipal, regional or national level, were seats of power in the places where liberal democracy now prevailed – equal players in a capitalist world.

The industrial landscape on the waterfront of Toronto about 1890. A birds-eye of factories with chimneys billowing smoke that symbolised progress, and the wealth and power of industry.

The Ontario Legislature in Toronto, constructed in the 1890s, and sited in a substantial open space in the centre of the city, is an example of the way governments in the Industrial Age demonstrated their authority by making a grand place for themselves.

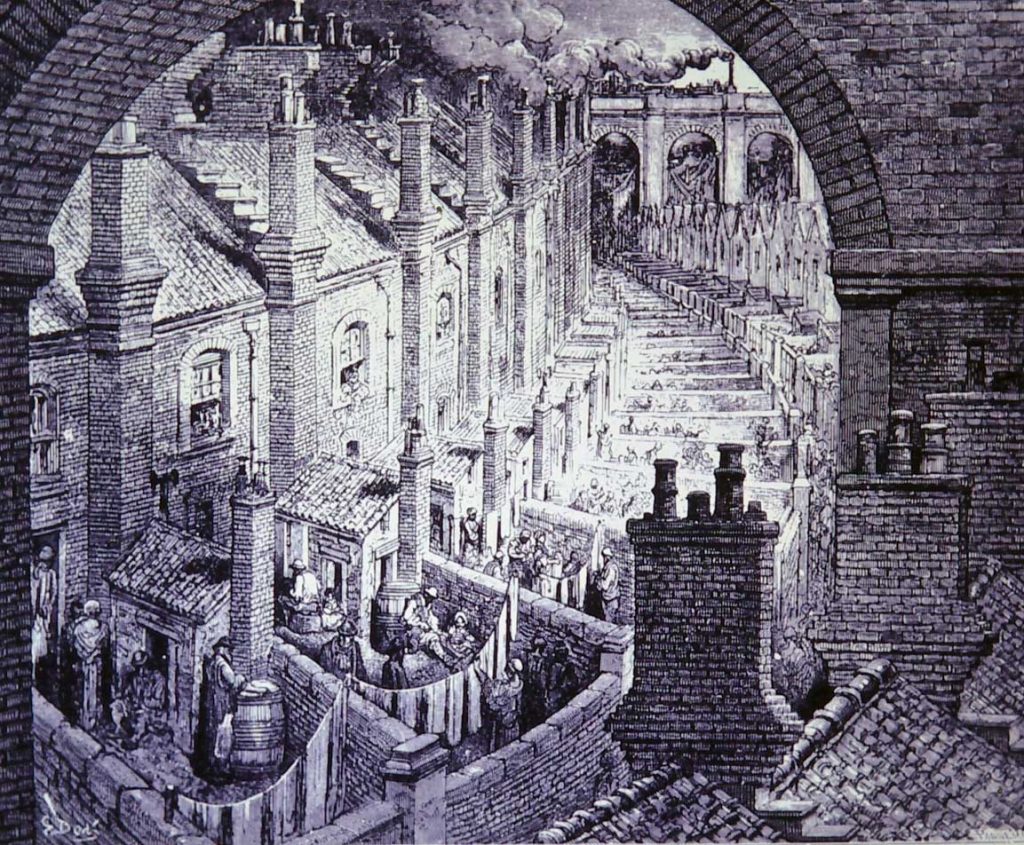

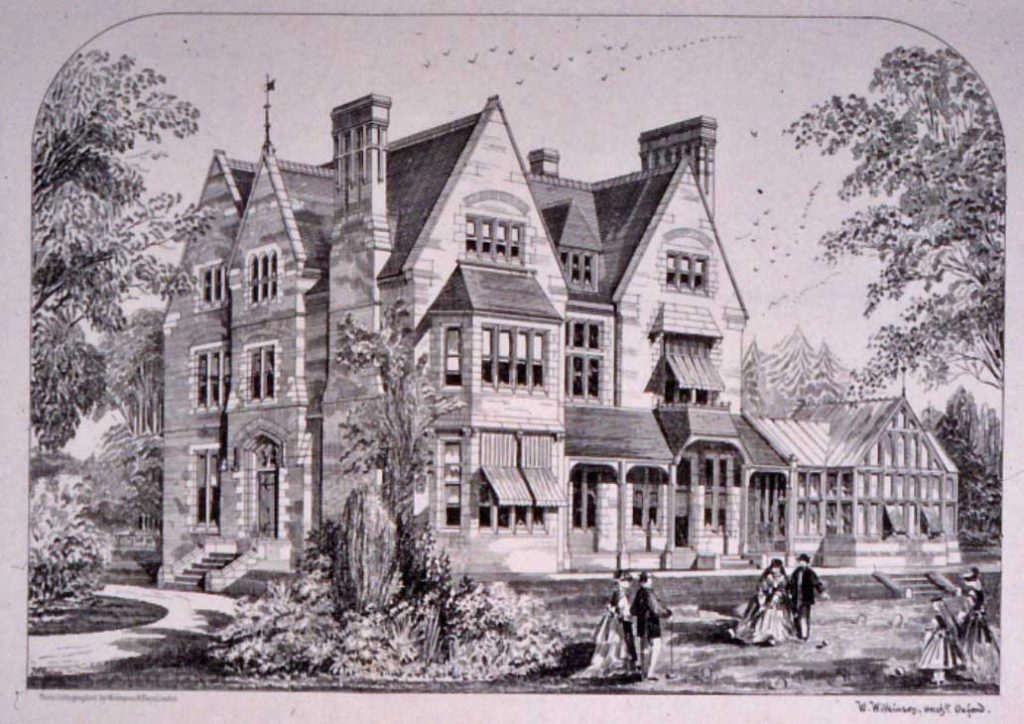

In spite of these symbols of progress, in the Industrial Age cities were for the most part unpleasant, polluted, congested and uncomfortable places, especially for the poor but also for the well-to-do, because smogs, unpaved streets covered in horse manure, and epidemics of cholera and typhoid caused by unsanitary conditions, did not respect class differences. The more affluent were able to escape the worst discomforts by locating themselves on relatively pleasant hilltop locations, or moving to villas in suburban developments easily accessible by railways or streetcars. These were well-built in whatever revival style was fashionable at the time – Gothic, Italianate, Neo-Classical, Queen Anne – and many are still attractive residential districts. And over the course of the 19th century there were several major innovations that improved in the quality of places for everyone. For instance, in 1858 very hot weather in London caused unbearably foul odours to rise from the Thames, an event known as the Great Stink, and this led to improvements in urban sewerage systems (it probably helped that the Houses of Parliament are next to the river). And as urban places grew, governments ensured that they included schools, hospitals, and public parks such as Central Park in New York, and urban filtration and water distribution systems. These improvements must have contributed to the continuing rapid population and urban growth.

An engraving of London by Gustave Doré 1870

A late Victorian suburban house in Oxford

Contrasts in places where poor and rich people lived in the Industrial Period

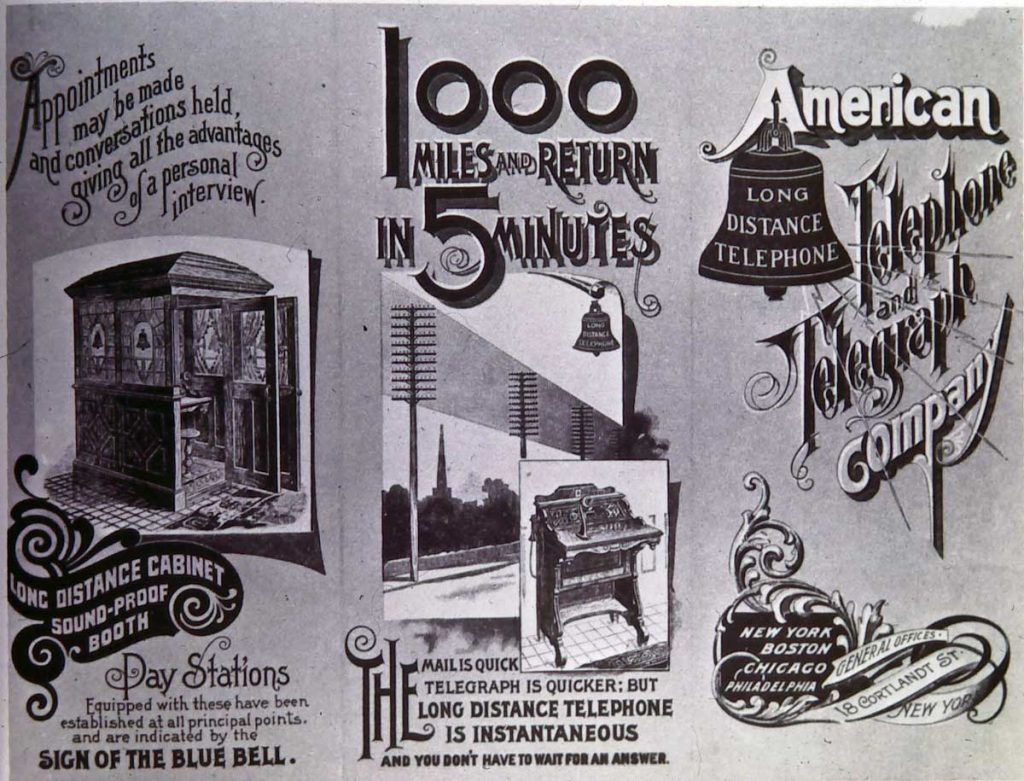

Over the course of the 19th century relationships between places underwent a radical change. Railways and the telegraph, and then electric streetcars and telephones, worked in concert to collapse time and space, the former by moving goods and people at previously inconceivable speeds, the latter by sending messages faster than messengers. What had previously been remote was made quickly accessible, locally, regionally, nationally and globally. By the 1880s suburbs were expanding rapidly along streetcar lines, Europe and India were laced with networks of railways, North America had been crossed by transcontinental railroads, and submarine cables had been laid across the Atlantic and Pacific linking Europe, Australia and America, distributing technologies, people, products, architectural fashions and practices for making places around the world. In a single century there had been a metamorphosis affecting both the identities of places and relationships between them.

This advertisement for AT&T in the 1890s captured the radical change in the relationship to distant places that had occurred in the 19th century because of innovations in communications.

Places (and Placelessness) of the Modern Era

During the 19th century there were many attempts to find ways to redress the social and other problems of industrialization and rapid urban growth, especially the living conditions in the places of the poor. Towards the end of the century these coalesced into socialist and reform movements that received boosts from two popular speculations about utopian places in which pollution and social injustices had been resolved: Edward Bellamy’s Looking Backward: 2000-1887, and William Morris’ New from Nowhere. These appear to have informed a remarkable proposal in 1898 by Ebenezer Howard, who had no background in politics or planning, for what he called “garden cities,” places that would offer an alternative to industrial cities.

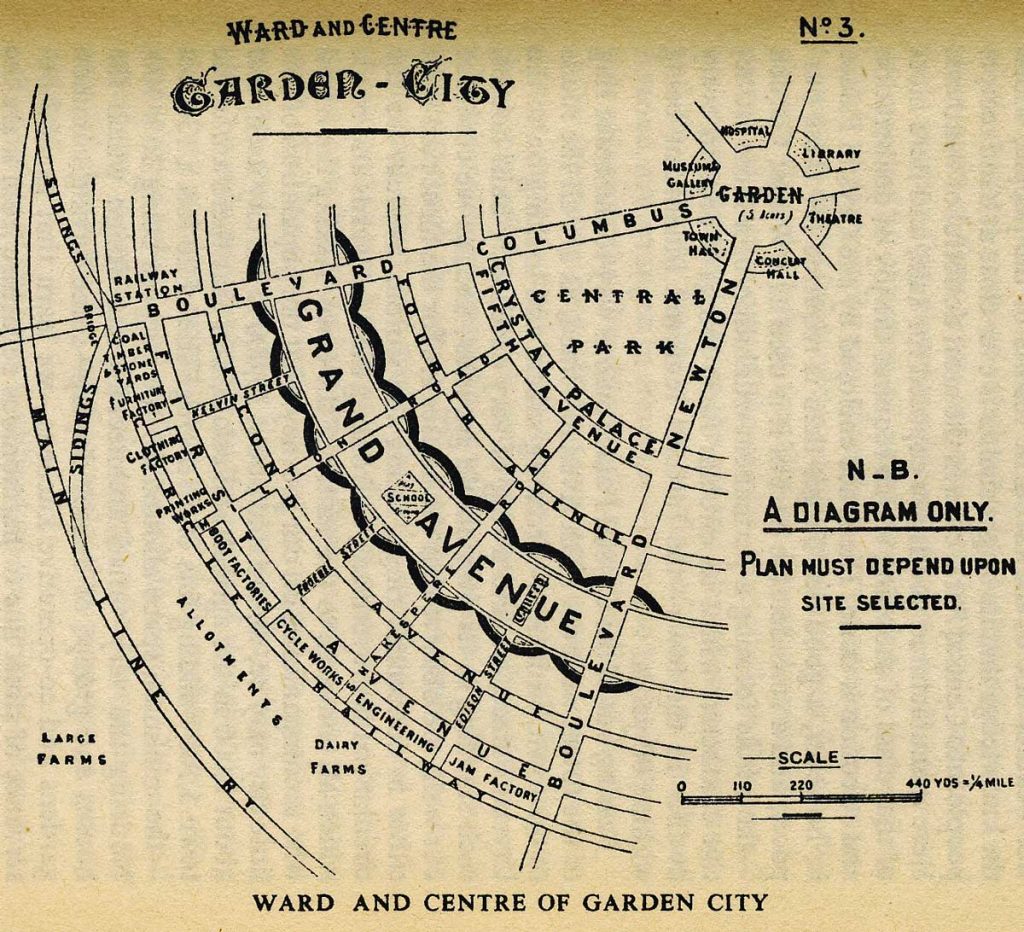

A conceptual diagram from Ebenezer Howard’s proposal for garden cities. On the outer ring are farms and allotments, then an industrial zone serviced by railways, areas for different types of housing, a ‘crystal palace’ or shopping area, and a central public park. This comprehensive way of thinking about planning places was entirely new. The geometry of this diagram was not what mattered, but the acknowledgement that all these components had to considered.

From the perspective of place what was remarkable about Howard’s proposal was that his plan was less about street patterns, which had been the focus of city planning from ancient Greece to the Age of Reason, than about creating a sort of place that would address people’s everyday needs in a way that was both economically viable and equitable. The innovative strength of his proposal attracted immediate and widespread attention, and within five years of its publication a company had been formed and land acquired to create a prototype garden city at Letchworth in England. Garden cities and new towns, following more or less along Howard’s lines, were subsequently constructed in many regions of the world. More significant is the fact that the garden city is an essential foundation of the approach to urban planning that is now used around the world, and addresses physical, social and economic aspects of how places are created and modified.

An example of the type of housing built about 1908 in the first garden city at Letchworth in England. This building was a co-operative where Ebenezer Howard chose to live – a very different place from even the wealthy suburbs of industrial cities.

Whether by chance or because of some ineffable spirit of the time, the proposal for garden cities was one of several innovations and inventions in the first decade the 20th century that have had ramifications for places. Rutherford’s ideas about nuclear physics and Einstein’s on relativity (that led to atomic weapons and the constant threat they pose for all places); the abstract art of Picasso, Braque and others (which redefined aesthetic standards); Ford’s mass-production of automobiles (which resulted in due course in automobile oriented urban development); Marconi’s wireless transmission across the Atlantic and the Wright brother’s first controlled flight (which reinforced and extended the shrinking of distance and interconnections between places that had begun with the telegraph and railways); and the conception by Adolf Loos and other European architects of a modernist, undecorated way of building that deliberately turned away from everything old and looked to the future.

The Steiner House by architect Adolf Loos, built 1910, bore no relationship to the Queen Anne and Gothic revival houses of the 1890s, or indeed any former styles of architecture, but would not look out of place if it had been built in 2010. It rejected all revivals and decoration, use new materials, and was a prototype for modern design.

This remarkable burst of innovative thinking was interrupted by the First World War, then in the 1920s and 30s it was reinforced, for instance, by modernist designers and architects at the Bauhaus and the architect Le Corbusier. They developed modernist designs for almost everything – dishes, chairs, light fixtures, houses, apartments, (even, in Le Corbusier’s case, entire cities) that were considered efficient, progressive and ideally could be mass-produced. Their approach to architecture used modern materials of glass, steel, and concrete, took advantage of the clean energy of electricity, and had plain, unornamented surfaces. It was called the International Style, and as the name implies, it was considered equally appropriate everywhere. It was, in other words, deliberately intended to be placeless. It has been used ever since, with some refinements, for commercial, institutional and high-rise apartment buildings around the world, for airport terminals, hospitals, hotels, shopping centres and gas stations. It is placemaking that is always familiar and provides no surprises.

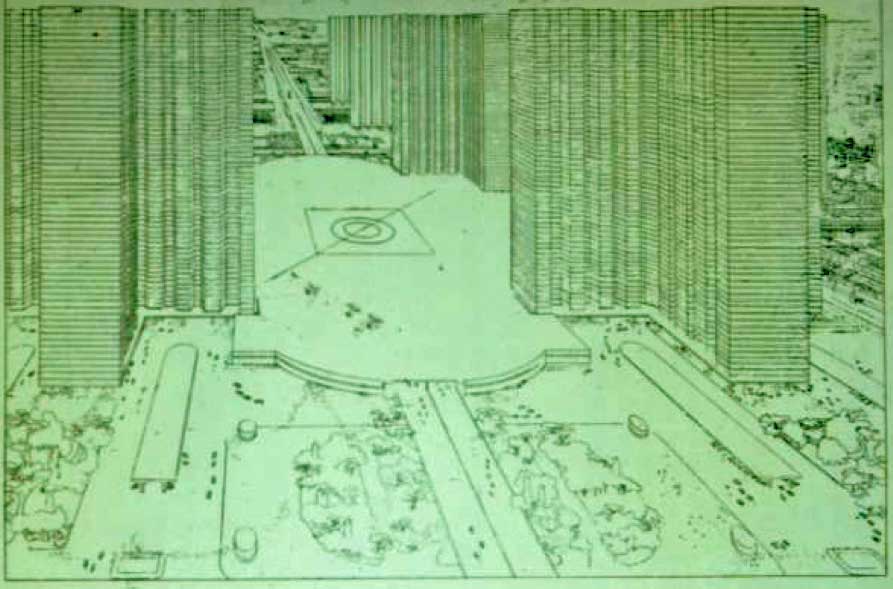

On the left, Le Corbusier’s 1930 proposal for an entirely new type of urban place, a Radiant City, of 60 storey cruciform skyscrapers that would free up the ground level for open spaces, or, in this case in the centre of the city for expressways, and (remarkably) and airport between the towers. Nothing on this scale was ever built, but Corbusier’s ideas have influenced modern places – on the right are cruciform towers of about 20 storeys, built about 1980 in Mississauga, a suburban city adjacent to Toronto in Canada.

As architects and others developed their modernist, international approaches between the two world wars, city officials found ways to adapt cities to social and technological changes. Zoning was introduced as a way of separating undesirable uses, such as abattoirs and office skyscrapers from residential areas, and quickly became a means for the segregation of most land uses – low density residential here, high density there, retail and industrial somewhere else – in effect dismantling places into component parts. To deal with rapid increases in use of motor vehicles, signs and signals were invented, different categories of roads were established with residential neighbourhoods identified as places to be protected from through traffic which would use arterial roads. Expressways were conceived (though few were built until after the Second World War. The first commercial airports were built. Billboards, neon signs, electric street-lights, gas stations, and much of the everyday paraphernalia of city streets that we take for granted, were introduced.

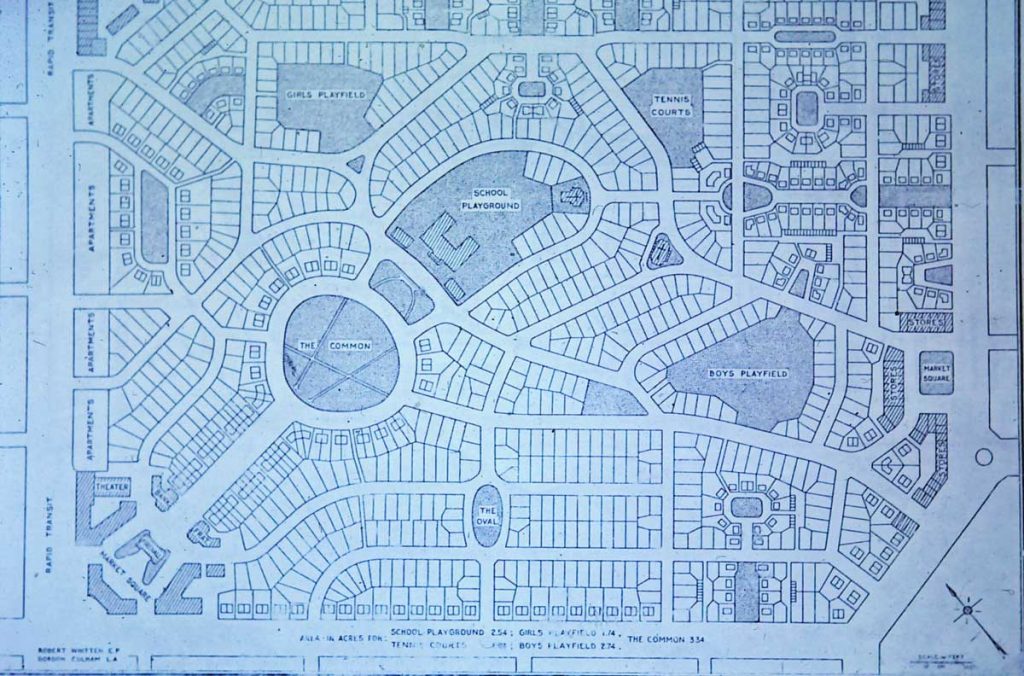

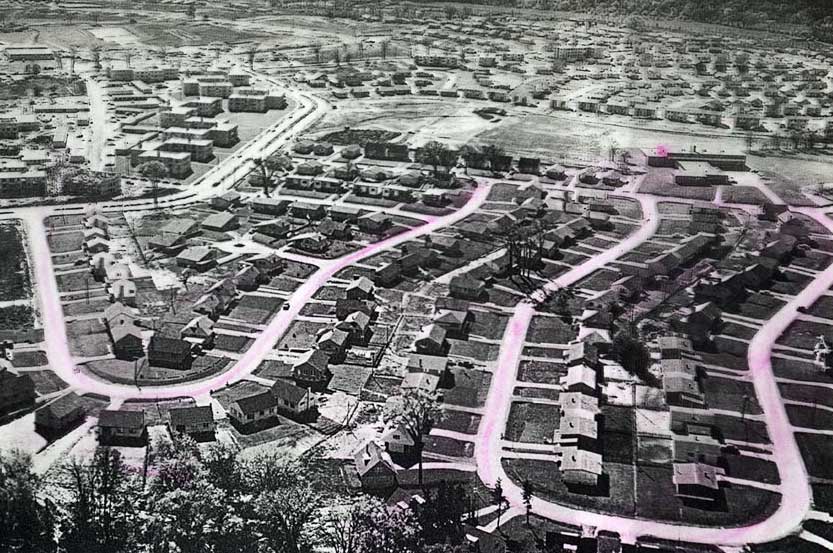

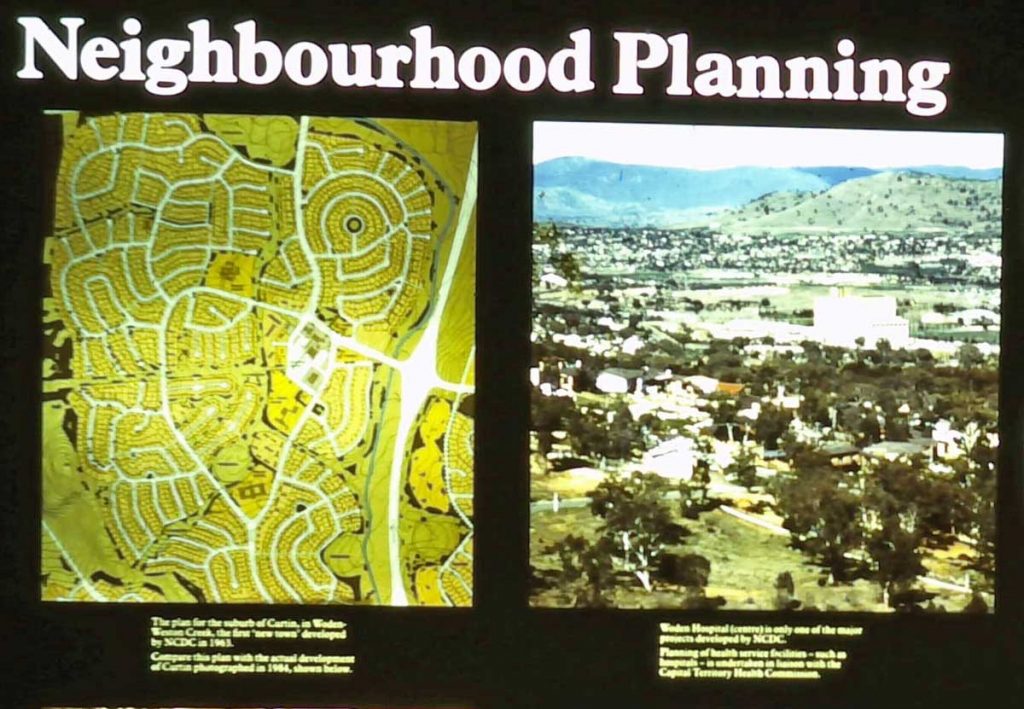

Neighbourhoods as new types of places. On the left, a diagram of a 1929 proposal for a neighbourhood unit by Clarence Perry shows a maze of curving streets and culs-de-sac for housing, with an elementary school and parks in the centre, and apartments and shops on the edges; the aim was to keep through traffic on arterial roads at the outside of the block. In the middle, curvilinear streets as part of the neighbourhood design of Don Mills, a 1950s new town development on the edge of Toronto. On the right, the idea of neighbourhood planning for suburban places explained in an exhibit in Canberra in Australia in 1985. Almost everything to do with placemaking in the 20th century was internationally shared.

The impact on places of all these innovations was quite limited because the Depression and the Second World War intervened. The war did lead to some unprecedented types of places and place experiences – vast cemeteries, concentration camps – and to deliberate campaigns of place destruction by bombing. But it was in the decades after t1945 that the approaches to placemaking developed earlier in the century were extensively adopted. And this happened in the context of a widely held view that whatever was old – buildings, street patterns, the attitudes that had led to the war – was obsolete, best removed and replaced with something modern and progressive. Modernist practices were efficient, affordable, comprehensive, made use of new technologies and available materials, and responded to new consumer trends such as automobile use.

In the 1950s war damaged parts of cities in France, Germany, Britain, the Soviet Union and Japan were rebuilt using versions of modernist approaches for making places. This was done under the aegis of comprehensive town planning, which was legally adopted in many countries (all previous planning had been advisory). Comprehensive planning considered requirements for different types of housing, schools, public parks, retailing, and traffic, was made a requirement in many countries (before the Second World War it had been mostly voluntary). In Britain it was the basis for designing new towns built from scratch on greenfield sites. In North America social housing projects of tall apartment towers designed along lines developed in the Germany in the 1920s replaced entire city blocks of old houses, while developers created automobile-oriented suburbs of boxy houses neatly arranged on mazes of curvilinear streets. Shops and services in new towns and automobile suburbs were arranged in commercial strips, drive-to plazas, enclosed shopping malls. Many stores in those places were outlets of multi-national corporations using standardized signs and selling the same products. Parking lots became a major type of land use. Zoning ensured that different types of land uses were separated. Arterial roads and networks of expressways continued the process that had been started by railways of redefining relationships between places by making everywhere accessible by car.

On the left, Cabrini Green in Chicago in the 1990s, showing the apartment slabs built in the 1950s as part of an urban renewal project to replace the sorts of houses and commercial blocks shown in the foreground. The slabs have now been demolished. In the centre, Soviet style apartments from the same period in Tallinn in Estonia. On the right, suburban Paris in 2005. High rise apartments were a new type of accommodation that was internationally popular in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, both as a way to replace old or war-damaged parts of cities, and to provide social housing. While all these projects were in some limited sense places, each with its own name and location, they ignored local environments and culture and were similar in form wherever they were constructed, so they were also manifestations of placelessness.i

This functional, modernist approach to making modern places can be understood as a response to the need after the Second World War both to rebuild and to accommodate very rapid population growth, almost all of it in urban areas. Between 1950 and 1970 world population grew by about 1 billion; Europe by 100 million (the equivalent of a city with a million people every two years) and the US by 50 million. Modernist placemaking provided ways to do this while improving living conditions and meeting people’s expectations for a better quality of life. It was used, with minor variations, almost everywhere – in Britain, France, the United States, Australia, Japan, the Soviet Union. The same sorts of apartment towers in the same sorts of clusters, the same classifications of roads according to projected traffic flows, the same gas stations, similar curvilinear street mazes in residential suburbs. In order to do this local traditions and ecosystems, old buildings and settlements, were treated as impediments to progress and growth. They were built over or demolished..

Commercial strips and the ordinary international modernism of the 1960s and 1970s was inherently placeless – similar designs, the same activities, the same multi-national corporations in urban places almost everywhere.

Of course, in some superficial sense each new town, housing project, suburb and modernist apartment tower was a place, a unique location, often with a name invented by planners or developers, somewhere people worked, lived and made their home. Nevertheless, the overwhelming effect of the landscapes created between 1945 and 1970 was one of diminished distinctiveness, of similar places offering similar possibilities for experiences, of no surprises, of placelessness.

A Summary of the Historical Periods of Places

• Ancient Greek places blended spiritual, aesthetic and intellectual qualities. Public places – temples and the agora – were for expressions of shared communal identity.

• Roman places demonstrated pragmatism and control that were part of an Empire with a consistent identity everywhere; spiritual life was largely domesticated, and public spaces were primarily for spectacles or displays of authority.

• Medieval places had an original character because previous history had been forgotten; their the focus was religion, both literally and symbolically, though there was parallel attention to trade and security.

• Places in the Age of Reason borrowed from Classical traditions to promote rational, geometric order, in part in buildings and estates that expressed the power of the aristocracy, in part by imposing rectangularity on landscapes and street plans, and in part by colonising and uprooting cultures which did not shared rationalist convictions.

• Industrial places reflected the utilitarian demands of growth, capitalism and unprecedented consequences of innovative technologies, including urban expansion, pollution and the collapse of distance as a barrier between locations.

• Modernity reinforced the collapse of distance, rejected the past, celebrated progress toward the future, and promoted standardization that encouraged uniformity at the expense of the identities of places.

A Shift to Different Approaches to Placemaking since About 1970

There has been a shift away from the placelessness of modernity since about 1970. Although modernist practices continue to be used they have been increasingly challenged by a widely shared recognition of the need to respect ecological processes and cultural heritage. At the same time many remnants of the industrial age – coal mines, old factories, railway lines – have been closed, dismantled or converted to other uses. There has been an enormous rise in global trade and international tourism, electronic communication has become part of everyday life, the world’s population has doubled, climate change has been identified and its consequences have intensified, migrations patterns have shifted, the deepest levels of poverty have decreased but inequality has increased.

I have reviewed these recent trends in three previous posts (Reinforcing Distinctiveness, Experiences, Theoretical Speculations). In the next post I will summarise them as part of a consideration of the implications of continuity and change for figuring how places might be made, redeveloped and managed over the course of the next few decades.