This post is the second in a series about the past and future of places. The previous one explained my overall aims and approach, and noted that my emphasis is on material places rather than the more abstract notion of place.

This is also the first of two specifically about the history of places that examine changes in the ways people have made and related to particular places since the first permanent human settlements were made about 12,000 years ago. I have divided this history into two parts mainly because I think it makes what would otherwise be a very long post much more manageable. I have take the year 1000 as a mid-point partly for convenience, but also also because evidence of how places were made and experienced before then is mostly in the form of ruins and archaeological sites, and since about then there are whole buildings, landscapes and parts of towns that are more or less intact and have been continuously used. A second post on the history of places considers, the Middle Ages, the Age of Reason, the Industrial Period and the Modern Era.

My hope is that this broad historical survey gives some indication of how places have changed over the course of human history, and will clarify whether we are currently going through another place shift, and, if so, how this might play out.

Approach and Initial Qualifications

Approach: I summarized my approach, which borrows the ideas of the historian Fernand Braudel, in a previous post. To that I will simply add here that here my aim is to identify historical periods which demonstrate consistency in the ways places were made and experienced. Evidence of placemaking practices can be seen in the street patterns, heritage buildings and archaeological traces of places that still exist [incidentally, the first widespread use of the term ‘placemaking’ seems to have been by archaeologists in the 1970s]. Experiences of and relationships to places, which are more difficult to ascertain retroactively, I will consider mostly in terms of advances in communication – roads, printing, railways and so on.

The periods I identify are mostly familiar ones, corresponding for instance to those in Lewis Mumford’s The City in History, and other historical studies. I illustrate them where possible with my own knowledge of particular places, especially in Europe and North America. The histories of places in Asia, Africa, and Latin America follow different paths, although advances in communications, colonialism and global trade since about 1500 have ensured that large swathes of recent place history have been shared across continents and cultures.

Some initial qualifications (actually determined by writing a couple of drafts of the history):

• Periods of places do not have precise start and end dates. Innovative practices and attitudes to place evolved over decades or centuries, came to prevail for a length of time, then were gradually replaced.

• The periods are generalisations about ways of making and relating to places that reflect a particular conjuncture of social and technological practices. In effect, they identify a distinctive and widely shared sense of place which reflected the spirit of the times.

• In each period there was a variety of different types of places, some wealthy, some poor, some the centres of trade and power, some remote and culturally resistant. In this brief history I am mostly interested in innovative practices that were widely shared, and I pay little attention to these non-conforming places.

• Many non-conforming places were ones inherited from previous eras. Sometimes these were little more than traces in ruins and names, sometimes they were almost complete landscapes that endured because there was no good reason to replace them, sometimes they have been manifest in revivals of values and architectural styles. These remnants indicate the importance of continuity in places, which I will examine in a separate post.

• Because the complete landscapes of places at any given time have always included a legacy of places from earlier periods, over the course of history this legacy has become both increasingly deep and more extensive. In other words, the current era has the greatest legacy of past places.

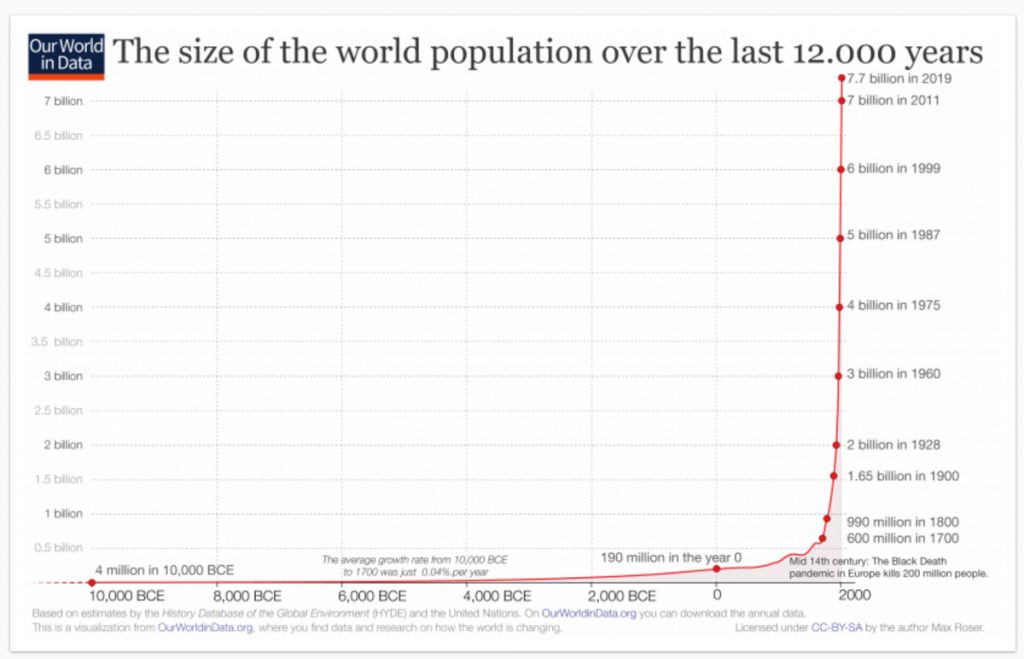

• And, very important, population growth and urban growth are two long-term, almost longue durée trends that underly the entire history of places. I will begin with those.

Population Growth and Urban Growth

Population Growth: Almost every century in the last 12,000 years has seen more people in more parts of the world, and since about 1800 there have been many more people in much more populous places. Graphs of population growth have two distinct elements. A gentle upward incline, almost horizontal, from about 10,000 BCE, when the world population is thought to have been about 4 million, to 1800 when it reached about 1 billion. And since 1800 an almost vertical line to 2020 and the present population of about 7.7 billion. There have been regional and temporary setbacks because of plagues, famines and wars, but these scarcely show. The fundamental fact is that the history of places is a history of accommodating population growth.

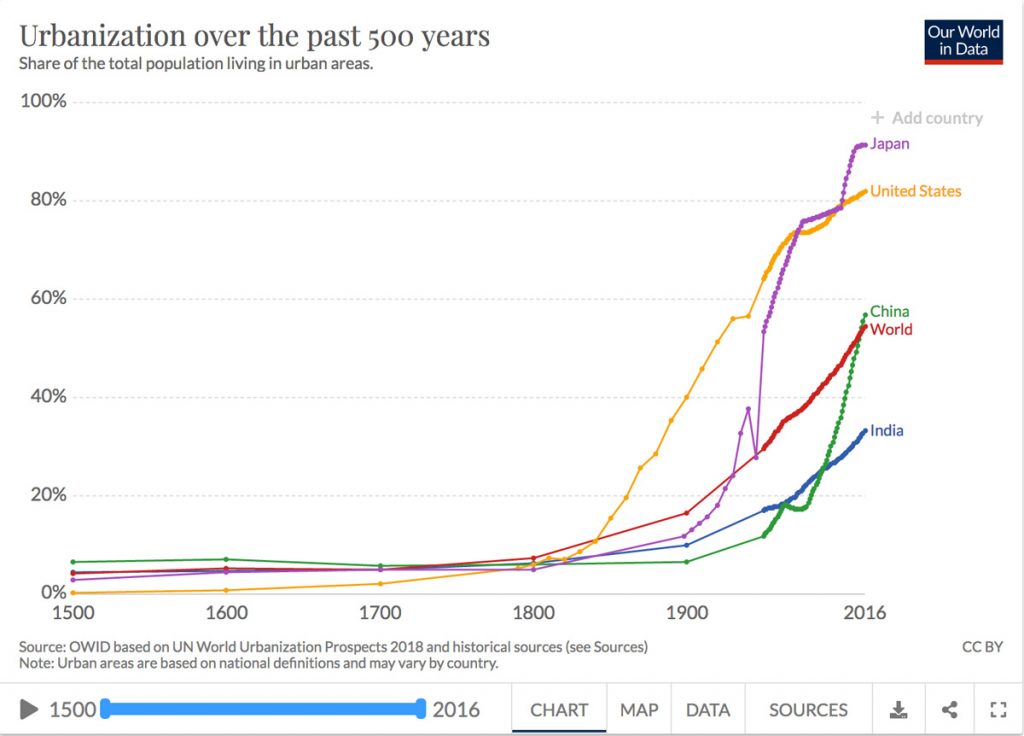

Urban growth. Population growth has been accommodated through diffusion – more people in more places – and in some ways from the outset but especially over the last two hundred years, by concentrating populations in urban places. The first cities (by current standards, actually small urban settlements with populations of a few thousand) were founded about 3500 BCE. Since then the tendency of cities everywhere has been to grow bigger. This is important to the history of place for two different reasons. One is that the proportion of people living in cities has steadily increased, though it probably remained under 10 percent in most parts of the world until about 1800. Since then it has accelerated faster than population growth, and now surpasses 50 percent for the world and 80 percent in most developed countries.

The second reason is that the history of cities is better documented in archaeological and written records than the history of rural areas. This means that there is a bias towards urban places, even when they held only a small proportion of the population, simply because there is more information about them.

The First Stable Places

Humans in the Stone Age depended on foraging and hunting, were continually on the move, and left little evidence of life in fixed places, presumably because they did not have the skills, means or inclination to modify environments. Nevertheless, they must have had the sense of place shared by all sentient beings that made it possible to find their way around, and to get back to wherever there was good shelter or food. In addition, cave paintings in Indonesia and Spain, dated respectively to 44,000 BCE and 35,000 BCE, indicate that they identified places with special significance.

Places as distinctive and enduring creations where people lived and died, and through which they connected to the world around them, begins with sites of stone monoliths, such as the one at Gobleki Tepe in Turkey made about 9,000 BCE. That, and other places with standing stones made over the course of several millennia (including Stonehenge about 3000 BCE), seem to have been associated with burial and/or ceremonial sites. Given the considerable work necessary to create those, and the fact that they were roughly contemporary with the gradual domestication of crops and animals, it is reasonable to assume that these were associated with settlements that provided a measure of security and made possible long-term connections between communities and particular locations. In other words, though there is scant archaeological evidence of domestic placemaking, it was probably then that enduring attachments to place first developed.

Earthworks and standing stones at Avebury in England are remnants of a ceremonial site dating from about 3000 BCE. The site is partially occupied by a village with medieval origins.

The Invention of Urban Places

A placemaking leap from small settlements and ceremonial sites to cities happened about 3,500 BCE in several locations around the world, most notably in the valleys of the Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia. These ancient cities were distinctively different from all previous settlements because of their relatively large and dense populations, planned streets laid out in a grid pattern, tall buildings, marketplaces, and grand temples. They were also centres of administration where writing on stone tablets was invented, perhaps to keep records of food supplies, and this presumably resulted in a class distinction between the literate few and everybody else. Although the great majority of people continued to live in small villages for the next three millennia, these early cities were a place invention that endured, steadily grew, and now prevails.

The first city in Mesopotamia is thought to have been Uruk, not far from what is now Baghdad. At its peak about 2,000 BCE it may have had a population of 50,000 but eventually declined for various environmental and political reasons, and was abandoned before 300 CE. What is often considered the first work of literature, The Epic of Gilgamesh, was written there about 1800 BCE in cuneiform on stone tablets. It begins with what probably the first written description of a place:

“The massive wall of Uruk, which no city on earth can equal. See how its ramparts gleam like copper in the sun. Climb the stone staircase, more ancient than the mind can imagine, approach the Eanna Temple, sacred to Ishtar, a temple that no king has equaled in size or beauty, walk on the wall of Uruk, follow its course around the city, inspect its mighty foundations, examine its brickwork, how masterfully it is built, observe the land it encloses: the palm trees, the gardens, the orchards, the glorious palaces and temples, the shops and marketplaces, the houses, the public squares.”

The Epic of Gilgamesh, Stephen Mitchell translation, 2004

Greek City-States and Knowledge of Other Places

The practice of building urban places slowly spread from Mesopotamia east to India and westwards to the Mediterranean. In Ancient Greece in the first millennium BCE the practice began to take on a distinctive character that is notable in part because such good archaeological and written records have survived. An important part of this distinctiveness was the development of city-states, essentially politically defined urban regions, each with a city supported by an agricultural economy, and with its own deity revered and honoured in temples such as those on the Acropolis for Athena, the goddess of Athens. Each city-state also had its own form of government to direct the everyday life of its citizens. The most notable was the democratic system invented in Athens, which redefined how at least some people related to place because citizens (which meant adult males, not women or slaves) could meet in a public space, the Agora, to debate and vote on matters that would affect life in the places where they lived.

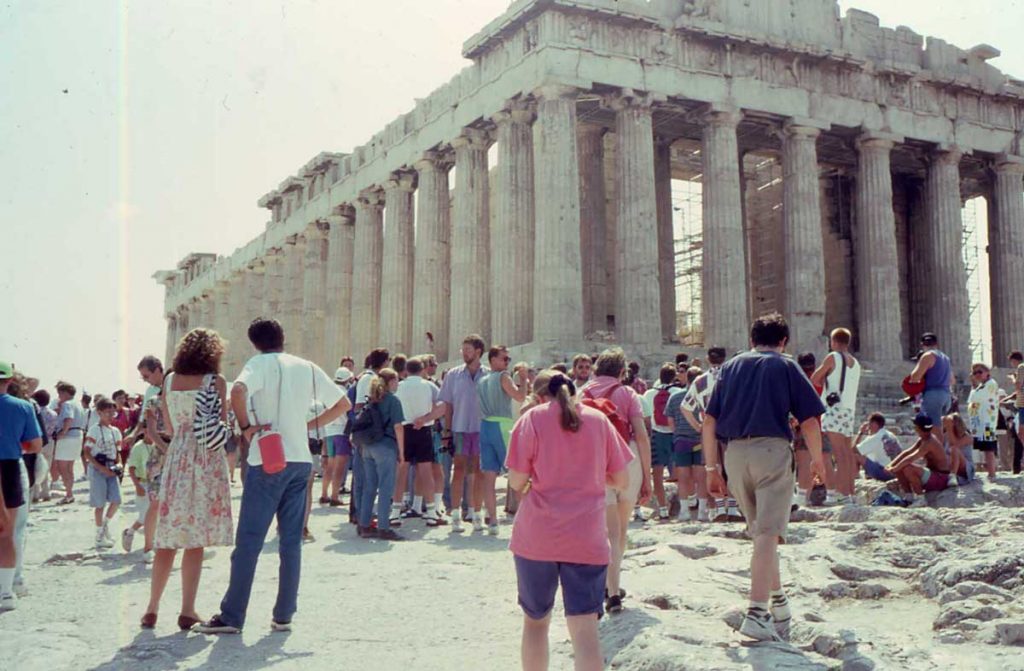

The Parthenon in Athens. The aesthetically meticulous architecture of Greek temples set a standard for western architecture that has been repeatedly revived and is still admired. In this respect, ancient Greek placemaking has echoed through the centuries

Some Greek cities, such as Athens, had inherited irregular or organic plans from earlier settlements, but where possible considerable attention was paid to creating a carefully arranged layout of spaces such as the Agora and sites of temples. In cities that had to be rebuilt (for instance after a war) these public spaces were incorporated into a layout system of rectangular city blocks in what can be considered the first systematic instances of placemaking and town planning,

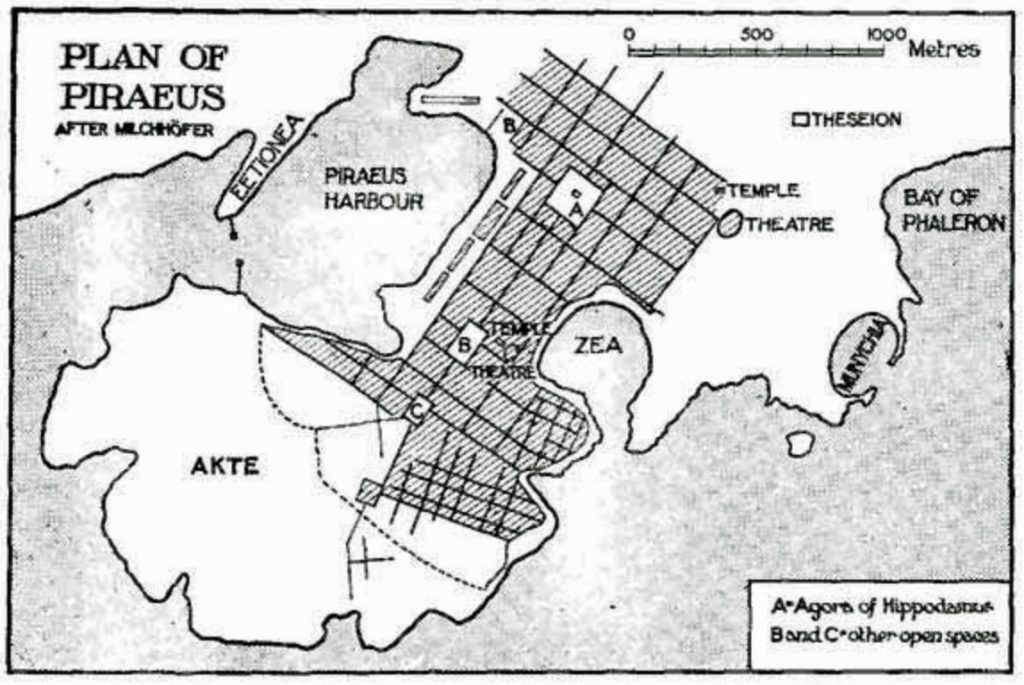

The plan for Piraeus, the port of Athens, about 450 BCE, by Hippodamus (considered to be the first town planner), showing rectangular blocks, with spaces for the Agora, and Temple and Theatre.

In Hellenic Greece people were often identified by their birthplace – Hippodamus of Miletus, Eratosthenes of Cyrene, and so on, and the intellectual culture included a desire to understand the world and its places. Eratosthenes, the person who is attributed with the invention of the word ‘geography,’ was for some years around 225 BCE the librarian at Alexandria, and his books, though all lost, are known to have included both a map and a set of descriptions of known countries. While Ancient Greece did not have an empire, its citizens explored and migrated to various places in their known world, in effect creating what in retrospect appears to have been a geographically open and extended sense of place.

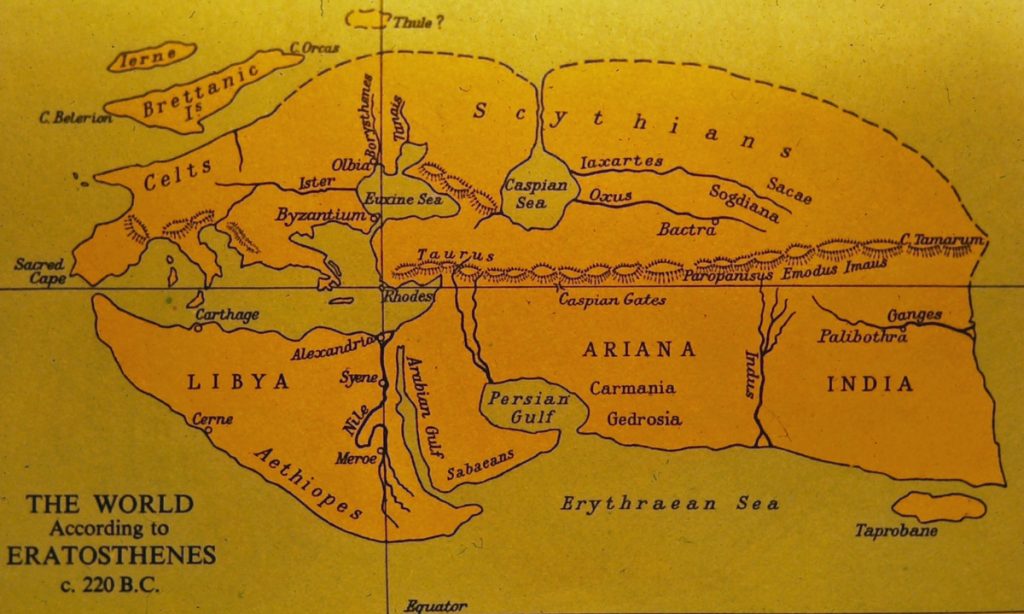

The known world according to the geographer Eratosthenes about 220 BCE, indicating the extended sense of place in Ancient Greece. The lines indicate suggest the way he accurately measured the circumference of the earth by measuring the angles of shadows in wells along the line of longitude

Standardized Places of the Roman Empire

About 150 BCE the city-states of Ancient Greece were assimilated into the expanding empire of the Romans, who then borrowed and adapted many aspects of Greek thought and placemaking, including architectural styles and aspects of town planning. But whereas the Greek attitude to place tended to be cerebral, democratic, spiritual and aesthetic, the Roman attitude was mostly administrative and practical. The Romans added innovations such as aqueducts, communal baths, and tenement buildings; amphitheatres for mass entertainment were substituted for theatres; monuments were built to honour emperors; religion was domesticated (every dwelling had its gods).

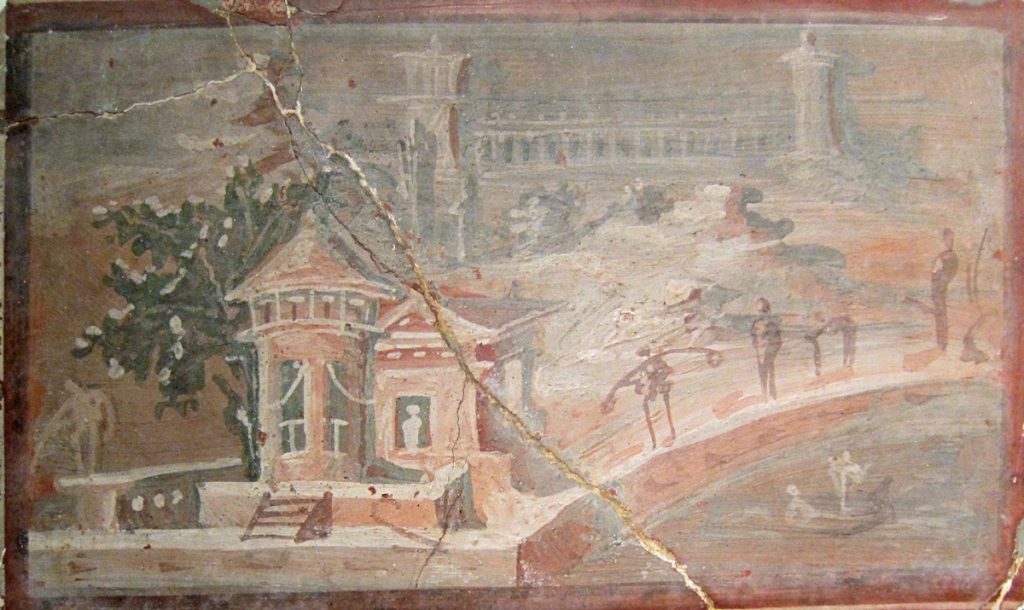

Roman placemaking. On the left, a domestic scene in a mural from Pompeii (now in National Archaeological Museum, Naples). In the centre, a commercial street with a stepping-stone crosswalk that allowed wheeled carts to pass. On the right, the Arch of Constantine (built to celebrate his military victories) and the Colosseum in Rome.

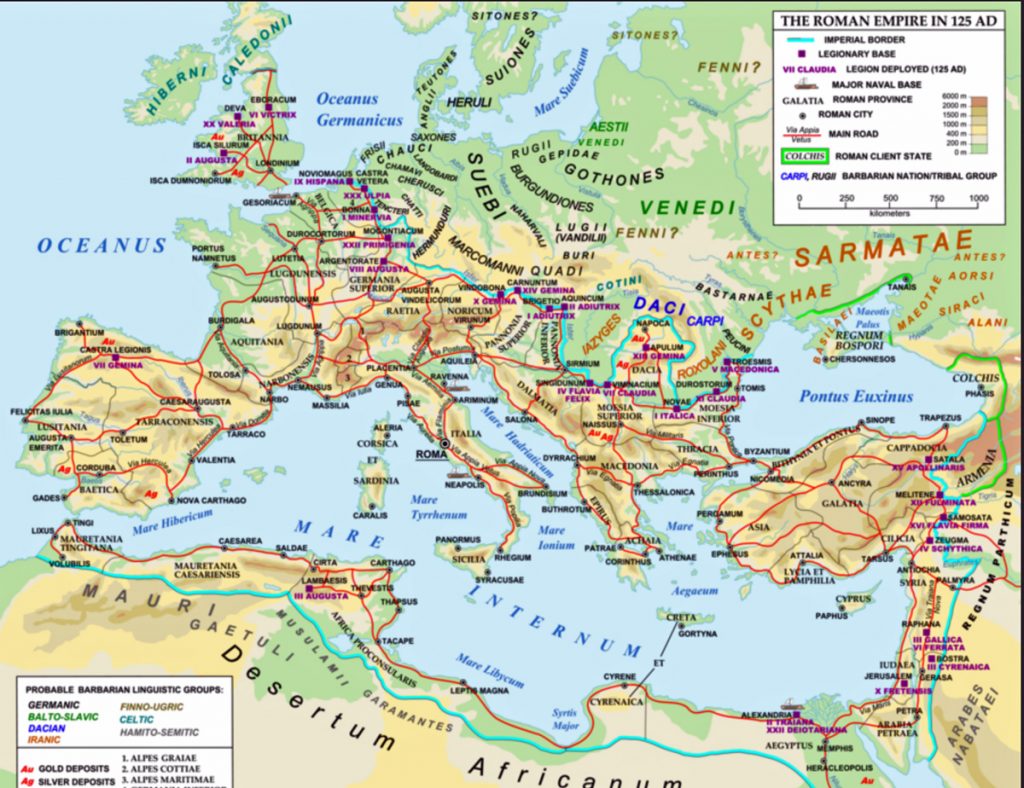

Perhaps most notably in terms of impacts on place, the Romans developed a continent wide network of roads that facilitated both communications by messages written on papyrus and rapid deployment of troops. This network allowed the imperial centre of Rome to command an empire that came to include territory all around the Mediterranean, far into the Middle East and into Britain. Wherever those roads and trade routes led, new settlements were created along lines specified in the first century BCE by the architect Vitruvius, whose books precisely detailed site selection, grid street patterns, street widths and orientation, the location and character of colonnades, and the size of city blocks. The roads and settlements offered both security and comfort to local peoples and their places, who where assimilated into the Roman way of life.

Roman culture at the very edge of the empire. This is a reconstruction of a Roman bath in Caerleon, a frontier town and military camp in Wales (that also had a small amphitheatre). The swimmer and text are projections onto the pool. The inner circle says: ‘Natatio means a place to swim or float’ (and is repeated in Welsh on the outside).

The Roman attitude to place was described by the geographer Strabo about 10 CE. “A knowledge of places,” he wrote at the beginning of his Geography (section 1.2.12), “is conducive of virtue,” and and by virtue he meant living in harmony with nature. Geographers, with their knowledge of the cosmos, wide travel, and careful observations, were especially capable of evaluating places, and this enabled them to interpret the providential order of landscapes, to distinguish good sites from unpropitious ones, and to advise others, especially political and military leaders, on how to take advantage of them. Whether the leaders paid much attention to this advice is not clear, but there is ample evidence that the great Roman network of roads and trade routes carried fashions for amphitheatres, therapeutic baths, villas with under-floor heating and elegant mosaics, and carefully organised grid town plans throughout the empire. This could be considered an early form of placelessness, though Strabo’s remarks suggest that it did involve adaptations to the particularities of places.

Roads and trade routes do, however, run in two directions. As they took Roman culture to the frontiers, they also brought people from throughout the empire to Rome. At its peak the city had a population of about 1 million (perhaps 30 percent of whom were slaves). It had many of the elements we still identify with large cities – stadiums, centres of government, multi-story tenements, water supply and sewerage systems. But it was also filled with noise, congestion, inequalities and what Lewis Mumford ( The City in History, p.237) describes evocatively as “megalopolitan elephantiasis.”

The Dark Ages and the Disaggregation of Places

After about 200 CE the Roman empire began to decline for reasons that included corrupt emperors, widespread decadence, internal power struggles, overdependence on slave labour, administrative inefficiency, and a series of assaults by Saxons, Vandals and Goths that pushed back the frontiers and eventually reached Rome in 476 when the capital of the empire was moved to Constantinople. What happened to places during and after this decline is open to debate because between about 300 CE and 1000 CE there are few descriptions and little evidence of how people lived.

One view is that the decline of imperial control opened the way for decentralization and this led to an period of local independence and creativity. A more conventional view is that literacy and learning plummeted as government and administration collapsed, and that populations declined dramatically because of violence, starvation and disease (a devastating plague in 540 may have wiped out 1/3rd of Europe’s population, a sobering thought in 2020 as an epidemic of novel coronavirus spreads around the world and appears to be particularly acute in Europe). By the end of the 5th century the population of Rome had dropped to about 30,000, and people lived in the ruins of civilization. Elsewhere places were disaggregated, the infrastructure built by the Romans crumbled, towns and villages were abandoned or became barely self-sustaining, and the countryside was taken over by waves of immigrant invaders – Goths, Huns, Saxons or Vikings, depending on the specific region of Europe.

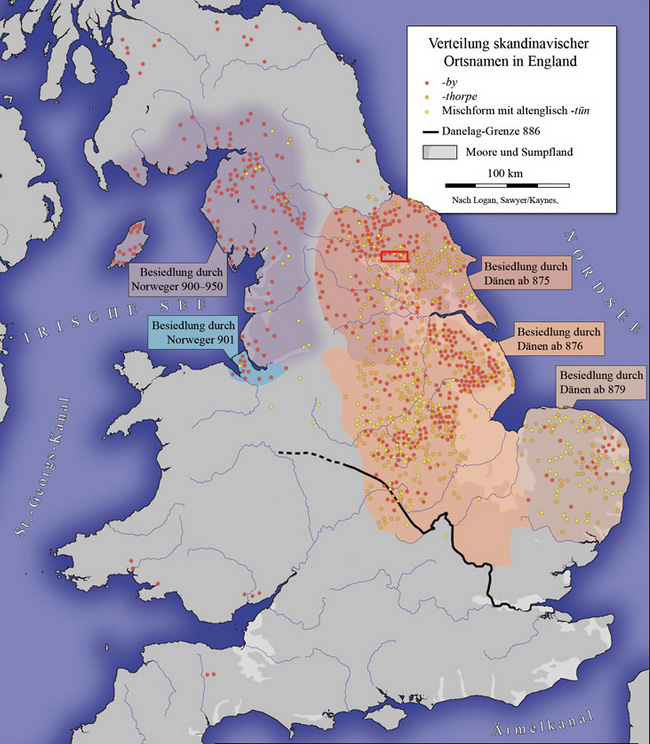

Those new immigrants left remarkably little evidence of placemaking and except for legacy of place names, which have filtered through into the names of towns and cities. In Britain, for instance, the suffix –borough is derived from the Anglo-Saxon –burh (e.g. Middlesborough) meaning fortified settlement, while –ham (Birmingham) and –by (Grimsby) both mean village, York probably comes from the Viking Jorvik. Normandy means the land of the North Men, or Vikings. Otherwise, the primary impact of the Dark Ages was one of taking places apart or allowing them to decay, of placeunmaking rather than placemaking.

Saxon (Danien) and Viking (Norwegen) place names in Britain that identify places settled during the Dark Ages by immigrants from Denmark and Norway

The History of Places continues in another post….

Places in the Middle Ages or Medieval Period that (about 1000 to 1500), the Age of Reason (about 1500 to 1800), the Industrial Period (about 1800 to 1900), and the Modern Era (about 1900 to 1970) is summarised in the post The History of Places Part Two: 1000 to the present