This is a short account of the various places where I have lived for at least several years, especially the early ones, because these have presumably informed my thinking. In contrast to much writing about place, which often emphasises roots, belonging and deep attachments, my place experiences can be appropriately described as peripatetic and multi-centred. I am not quite sure where I belong but I have always been engaged with where I am. I like to think this gives me both a resistance to nostalgia and a breadth of perspective but I could be wrong.

Place Beginnings: Carla Liotta, a psychoanalyst, writes about place in her book Soul and Earth that: “If one knows how to look, the beginnings hold everything.” This has been reinforced by many others, including Edith Cobb in her remarkable study of The Ecology of Imagination in Childhood.

The village church in Catbrook, made, I believe, from a prefabricated kit at the end of the 19th century.

I have ambivalent recollections about where I grew up. My earliest place memories are of a village, really a hamlet, called Catbrook situated on the Welsh side of the Wye Valley. It was a scattering of cottages and some small farms with a few cows, chickens and pigs mostly surrounded by forests. We were a single parent family, poor, living in a damp, cold bungalow that had an outside privy. Electricity and piped water came to the village in the mid-1950s; until then drinking water had to be carried in buckets from a community well. We had no family connections there, though my mother had grown up nearby. The village of Tintern, a couple of miles away in the valley, had a ruined Cistercian Abbey, painted by Turner and celebrated in poetry by Wordsworth. My village had no monuments; indeed there were no very old or distinctive buildings. The local church and village hall were both made of corrugated metal. [I drove through the village in 2009 and it has changed almost beyond recognition. Evidence of rural gentrification is everywhere. The little cottages have almost all been replaced by bulky houses with Land Rovers in the driveway. Sporty Spice of the Spice Girls is said to have a house there.]

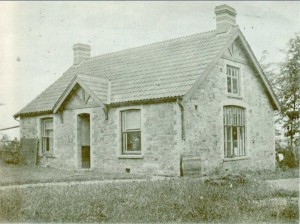

The house my grandfather built in 1908, when this photo was taken, and where I lived as a teenager. It still looked much the same eighty years later.

The place was not pretty, and there is little about it that makes me nostalgic. Nonetheless, the people living there had a mundane practicality that I still admire – they grew a lot of their own food, fixed machines, repaired houses, did what was needed to get by. And I did develop attachments to it because I knew its roads and fields and houses and people, played on the boys soccer team and shared in practical activities such as haymaking. These attachments were rudely broken when I was an early teenager and we moved four miles to another hamlet of scattered and humble cottages to live in the house my mother had grown up in. It had been built in 1908 by her father (my grandfather, who had died about ten years before I was born), who owned a small construction business. Although several of her sisters had died there, of influenza or TB, she had a deep affection for the house and the village. Long-time residents acknowledged her as fully fledged member of the community returning home. I think I was accepted because of this family association, but four miles could have been forty and my friends and childhood experiences had been left behind and I never felt as though I fully belonged.

London and Toronto: When I was eighteen I departed for university in London with few regrets about leaving these childhood places. As a student I lived in various types of accommodation (mostly in row houses) in Streatham, Alexandra Park, Camberwell, Vauxhall, Kilburn and Ealing, studied at LSE and King’s College on different sides of the Aldwych, survived the last great London smog in 1963 (when you really could not see across the street), and, except for one performance by the Rolling Stones in the Three Tuns pub at LSE, managed to miss most of the Carnaby Street swinging sixties stuff going on elsewhere in London. I spent five years in London, and enjoyed my time there but for all its attractions I didn’t develop a deep connection with it. Indeed, I have stronger memories of the shingle spit at Orfordness and the Dorset coast near Bridport, where I spent summers working as a research assistant on geomorphological projects, than I do of London.

In 1967 I moved to the PhD program in Geography at the University of Toronto, where, after an initial flirtation with natural hazards, my academic interest in place and placelessness developed. I made more or less annual trips back to my mother’s village, at first alone and then with my new Canadian family, and was able to witness a sort of stop-action sequence of remarkable changes. New motorways that reached less than a dozen miles away made the village easily accessible to London and other cities which had previously been a full day’s journey away. Many long-time villagers took advantage of resulting increases in property values and sold their damp little cottages to surgeons and television executives working in London or Birmingham, who promptly renovated and enlarged them beyond recognition. Other villagers did stay but had new houses built, or moved to more convenient sheltered housing in nearby towns; some bought villas in Spain. The village shops and then the village school closed and were converted to houses. Only a handful of the families I knew when I was growing up are still there.

The street in Highland Creek in eastern Toronto where I lived in the 1980s. This suburban community had many self-built houses from the late 1940s and had grown up around a 19th century village core.

I sold the family house when my mother died – it would have been impossible to maintain from the far side of the Atlantic – and my connections with the places where I grew up have been broken except for a field adjacent to the old family house that I inherited, still own and rent to one of the few remaining original families. It remains an enduring thread to my place beginnings in an otherwise peripatetic life. I have returned to London only as a tourist. I spent more than 45 years in Toronto, where my footloose habits seem to have persisted because I lived in seven different neighbourhoods, some in the central city, some in the post-war suburbs and others in the inner streetcar suburbs. For many of those years I worked partly at the downtown campus of the University of Toronto and mainly at its suburban Scarborough campus, where the main building is a massive poured concrete megastructure internationally famous among architectural historians and the location of David Cronenberg’s first horror movie. So rather than engaging deeply with one part of Toronto my experience was of living in a sequence of different places within the city. The one characteristic they shared was their walkability – even in my suburban places it was always possible to walk to local stores.

The view of Ballard Locks from our condominium in Seattle, Puget Sound and the Pacific on the left, and freshwater Salmon Bay and the canal to Lake Washington on the right. The installation in the foreground is called Waves and is much photographed and enjoyed by visitors.

Multicentred Place Experience: In 2010 we bought a condominium in Seattle to be closer to our grandchildren there. This is in an unremarkable 50 year old building with a remarkable view that looks over Ballard Locks, a major tourist destination and a scene of constant activity and entertainment as the Pacific fishing fleet and recreational boats come and go. I quickly developed a strong connection with this place where freshwater and ocean meet. However, taxation and health care issues restrict the amount of time Canadians can spend in the United States, and to be closer to our family we broke our ties with Toronto and bought a house in a former streetcar suburb of Victoria in British Columbia, one of the most walkable and bike friendly cities in North America. We regularly travel between Victoria to Seattle. Our other daughter moved to Ottawa to study and work, and now lives in Gatineau on the Quebec side of the the Ottawa River, so my family is scattered across North America, and my place commitments are divided between Toronto, Ottawa, Seattle, Victoria, and a field in Wales.

A Reflection on my Peripatetic and Liminal Place Experiences: Perhaps the main point to take away from this account of my lived place experiences, is that they have very little to do with roots, belonging, and the sort of nostalgic associations that frequently arise in discussions of place. My reasons for moving around have been mostly practical and family ones – to study, to find better accommodation when I was a student, when I married, when we had children, to move closer to my work, to downsize and move closer to my wife’s work when our children left, to move closer to our grandchildren. In retrospect, it also seems to be the case that many of my experiences have been at borders of things and ideas (the academic term for this is liminal). My mother’s house had a view looking across the Wye Valley from Wales to England; the Geography department I studied at in London was partly at LSE and partly at King’s College; as a discipline geography straddles social and natural science; my work in Toronto spanned downtown and suburbs; Ballard Locks are where ocean and freshwater meet; I now have allegiances on both sides of the American-Canadian border, to French and English Canada and to my field in Wales that offers a view of a bit of England. Place in my experience is not a simple, centred and enduring phenomenon.