[This includes a brief update in June 2023, at the end, responding to an article in The Economist]

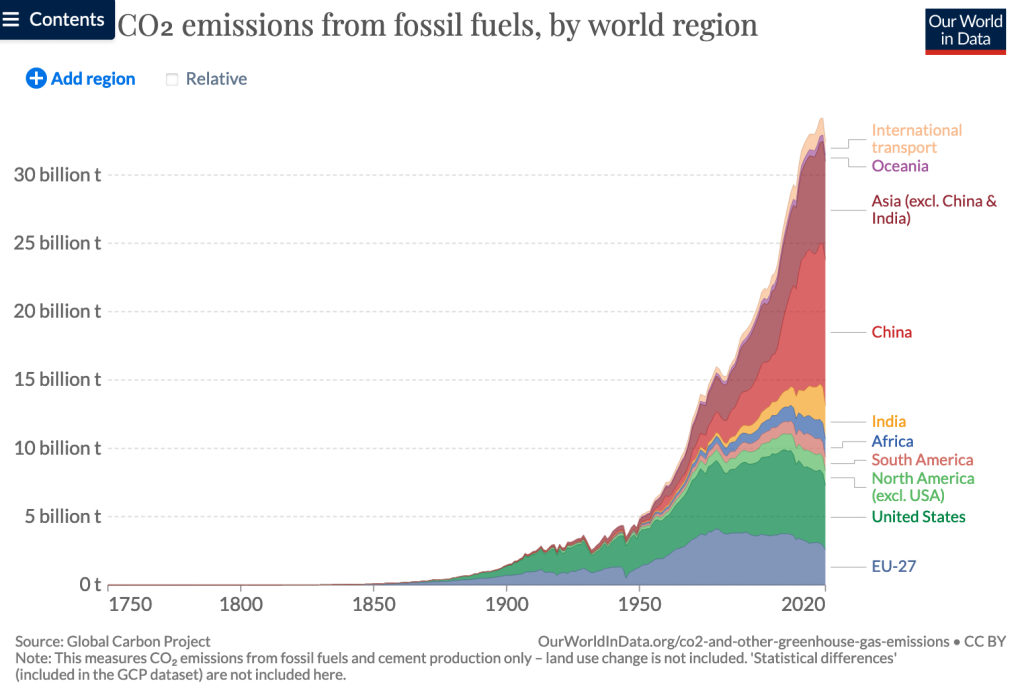

The dramatic economic growth of the last 250 years happened simultaneously with equally dramatic increases in population and concentrations of C02 in the atmosphere.

The specific question I address in this post is: What might happen with economic growth now that it has become clear that total fertility rates are dropping well below replacement levels in all high income countries and that the use of the atmosphere over the past three centuries as a free way to dispose of carbon generated by economic and population growth is now leading to rapidly increasing costs as a result of disasters caused by extreme weather.

Long-term parallel paths

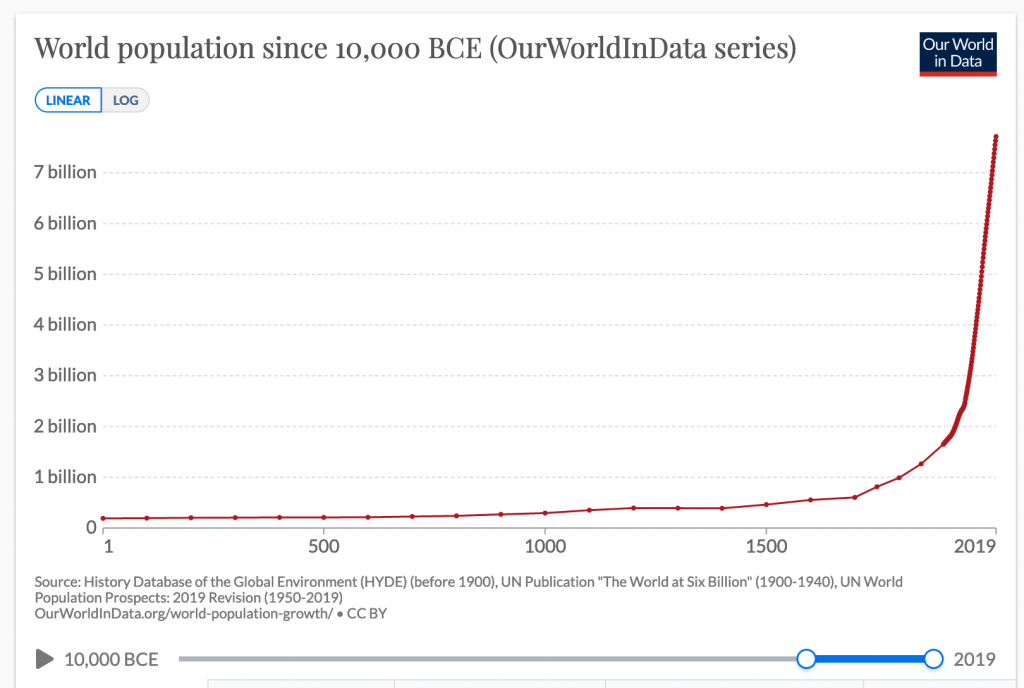

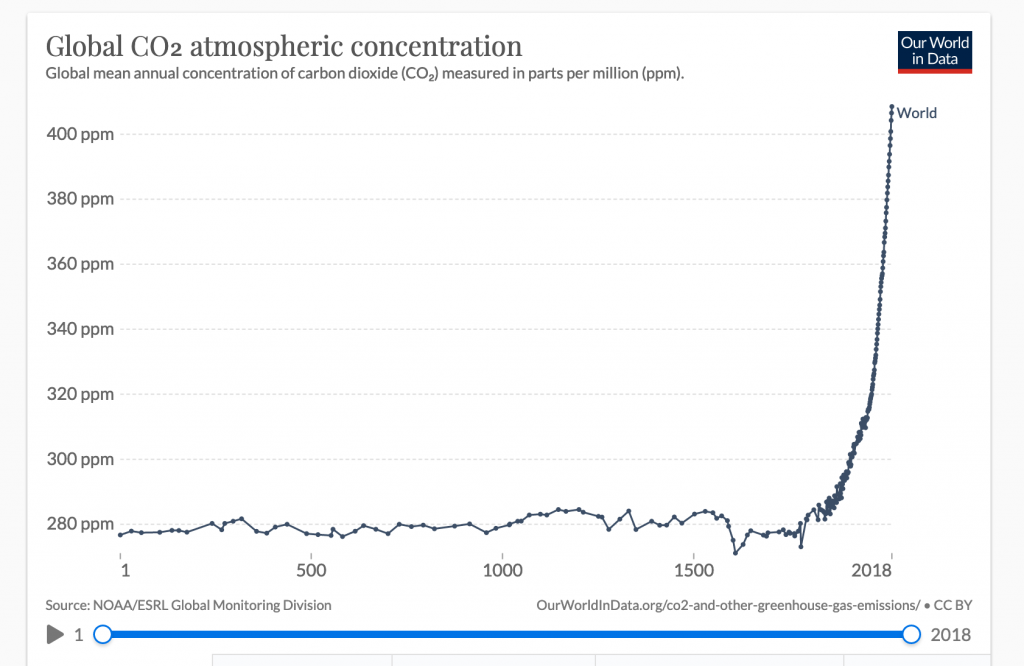

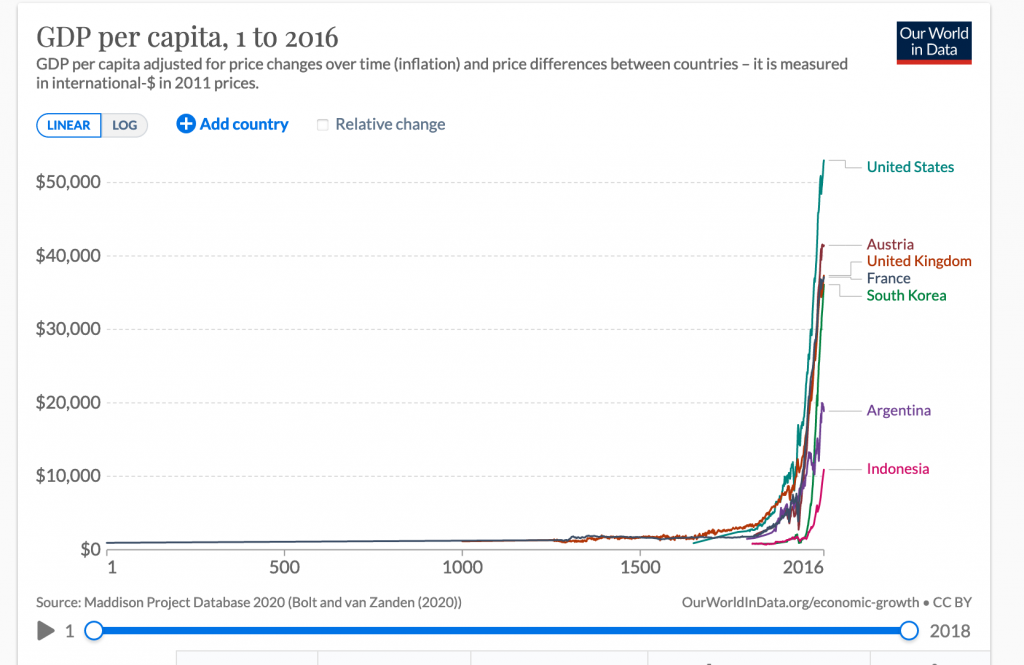

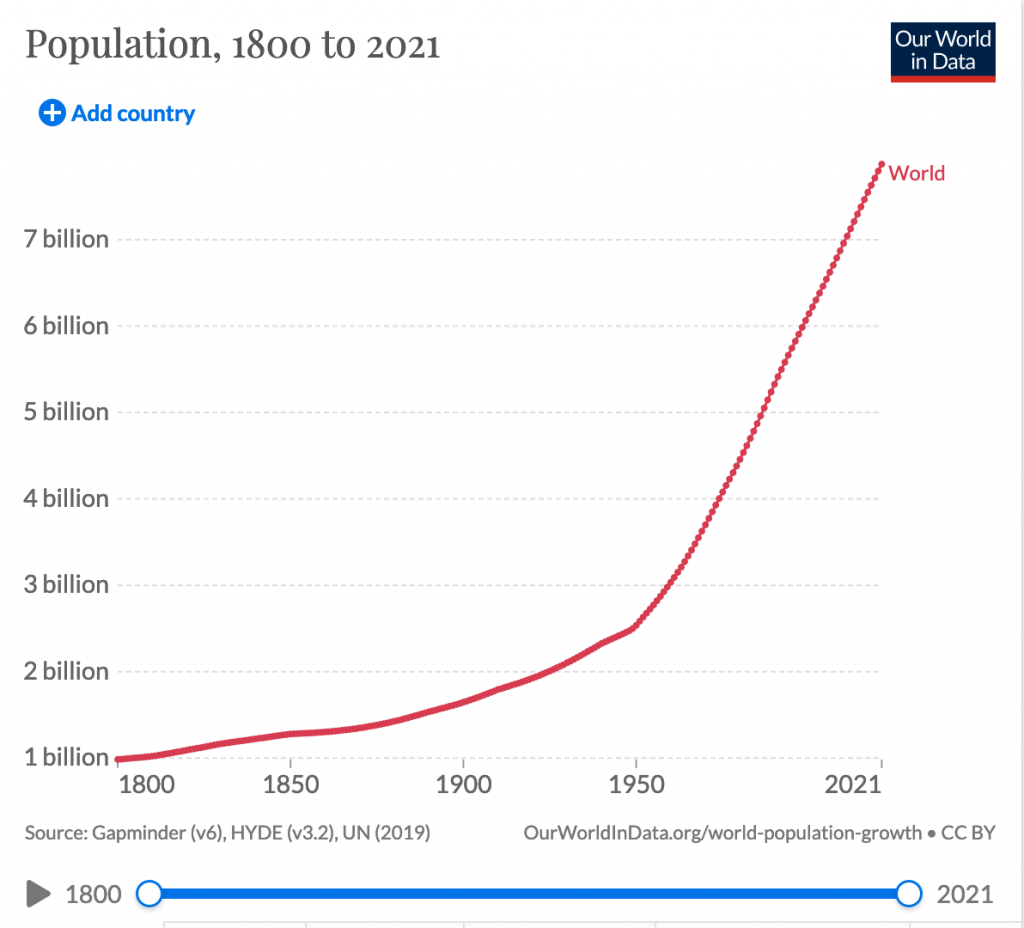

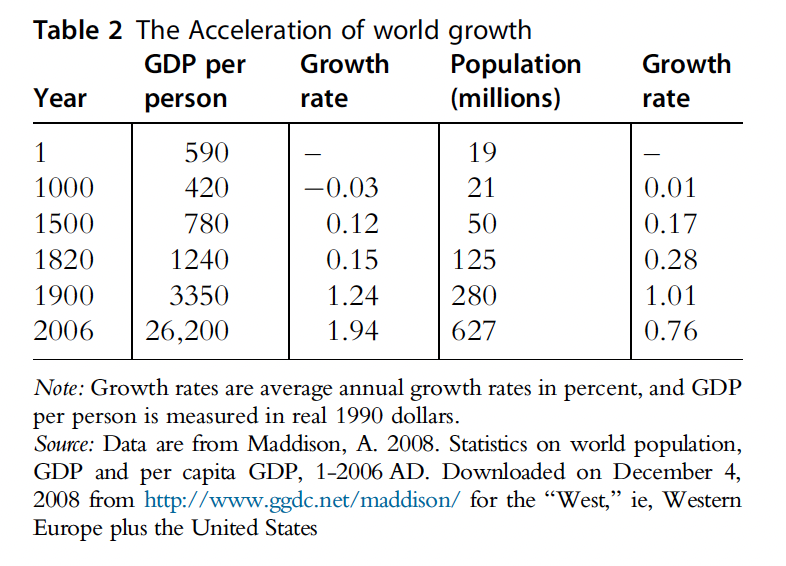

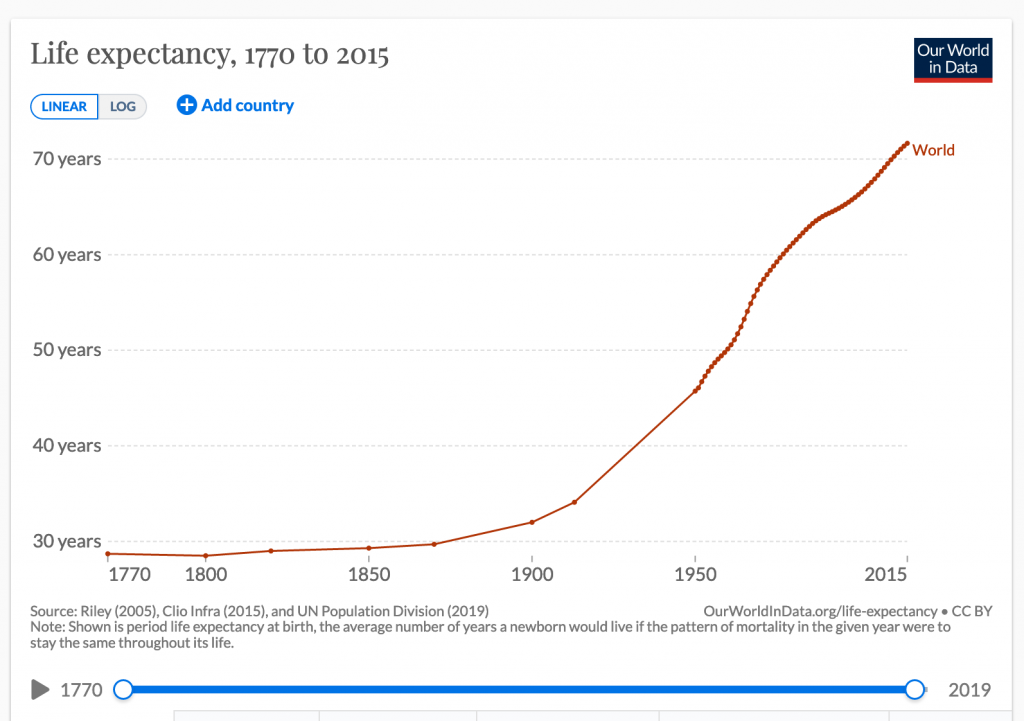

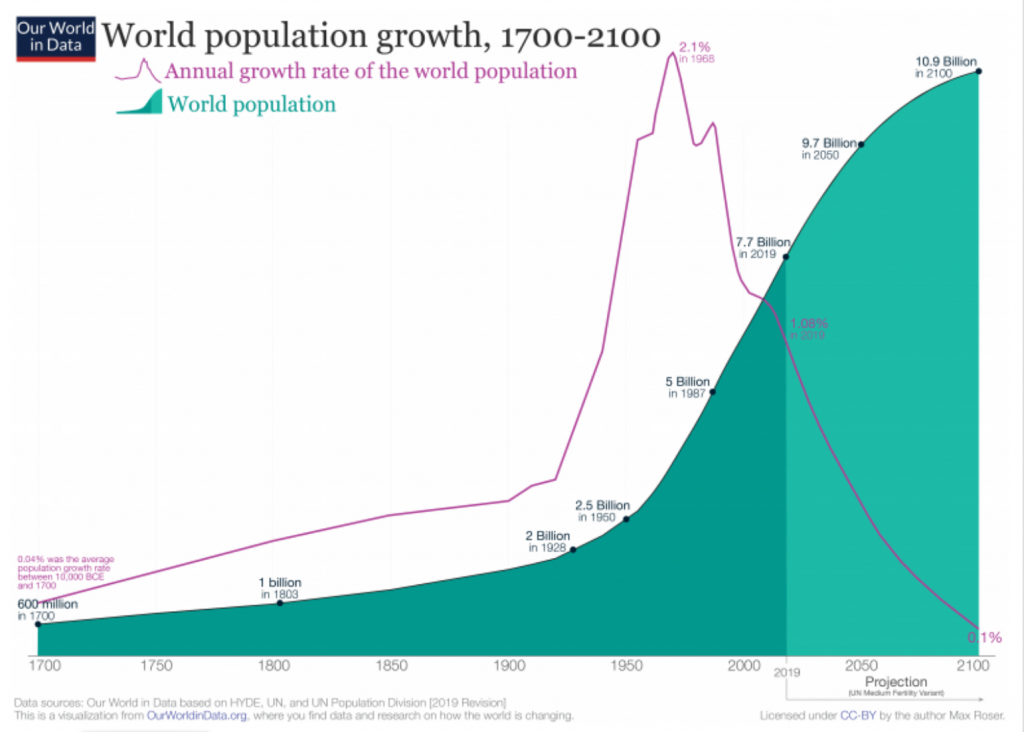

Graphs of changes over the last two millennia in global population, economic well-being (represented by GDP per capita) and concentration of carbon in the atmosphere all show a dramatic increase beginning in the 18th century and continuing to the present. These have been world-historical changes. Before the middle of the 18th century annual growth rates were about 0.01%, in other words scarcely changing. Then somewhere between 1750 and 1800 they all began to accelerate and since have grown at rates exceeding 1.5% a year, doubling every forty-five years or so.

(NOTE: many of the graphs I use here are screen captures from Our World in Data, an excellent source of data about many different topics. On their website many of the originals are interactive, allowing the horizontal time scale to be adjusted and/or different countries to be represented. These tools are not active here, and some embedded captions may be incorrect).

In terms of economic growth, regardless of what its origins are thought to be, there is no question, as the Bank of England has noted wryly, that it is quite a new thing. Before the 18th century overall standards of living, as well as populations and CO2 concentrations had scarcely changed for several millennia.

However, if they are considered just over the last 250 years, these changes seem more like smooth slopes than cliffs. Populations, initially in industrialized countries and later in less developed ones, began to edge up in the late 18th century and then to gradually accelerate until the mid-20th century. GDP per capita and CO2 concentrations followed a similar growth curve, though they lagged population growth by about half a century.

Interconnected growth

It seems to be the case that each of these three trends has contributed to the more or less simultaneous growth of the others.

Populations began to grow in European nations at about the same time the paradigm of economic growth associated with capitalism came to be adopted, and the same time as innovations in science enabled ideas about growth and progress to be translated into technologies that took advantage of the free good of the atmosphere as a way to dispose of CO2 emissions and increase productivity.

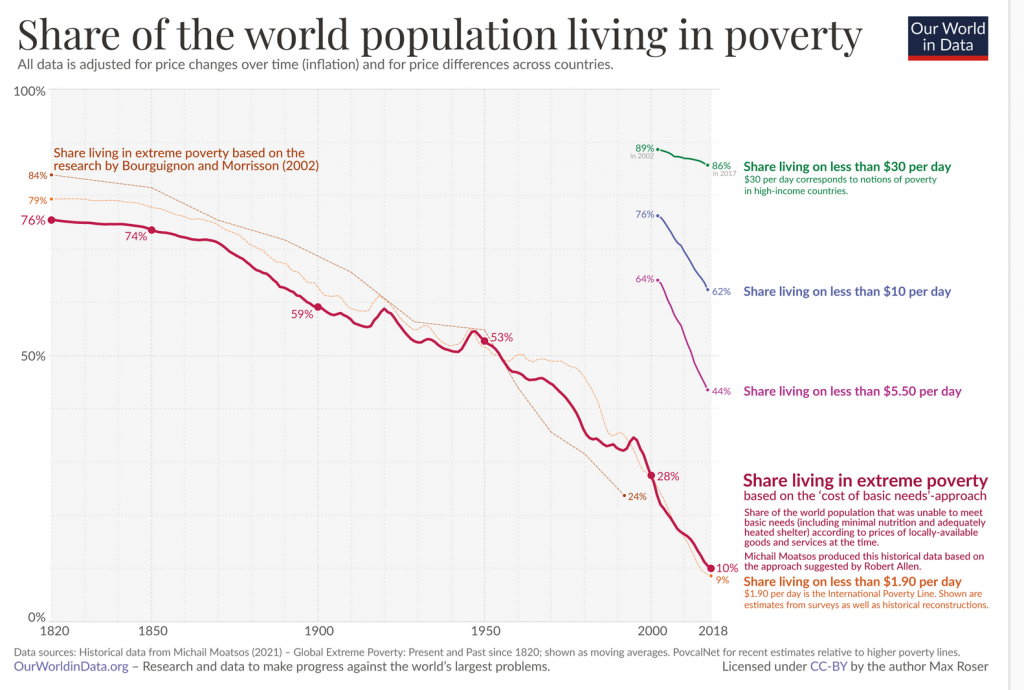

That increase in productivity led to higher GDP per capita and less poverty, which contributed to a decline in child mortality, which led to faster population growth, which (together with colonial expansion and global trading), provided larger markets for industrial goods, the production and use of which led to more carbon emissions, and so forth up the last quarter of the 20th century. In other words, population growth facilitated economic growth even as it was itself facilitated by the benefits of economic growth.

There was concern in the early 19th century that rapid population growth would lead to deprivation because food production could not keep pace with it. This turned out to be unwarranted because after about 1850 annual rates of economic growth (as reflected in GDP per capita, increased life expectancy and reductions in poverty) came to exceed rates of population growth. By 2006 global rates of annual increase in GDP per capita, at 1.94%, were almost three times the population growth rate of 0.76% per year.

What this suggests is first that population growth was, and in some places still is, an important initial stimulus to economic growth, and secondly that at some stage economic growth begins to occur independently.

Now, however, it seems possible that this independence might be threatened, partly because of falling population growth rates and declining populations, and partly because of the rapidly increasing costs of climate warming that are a consequence of carbon concentrations.

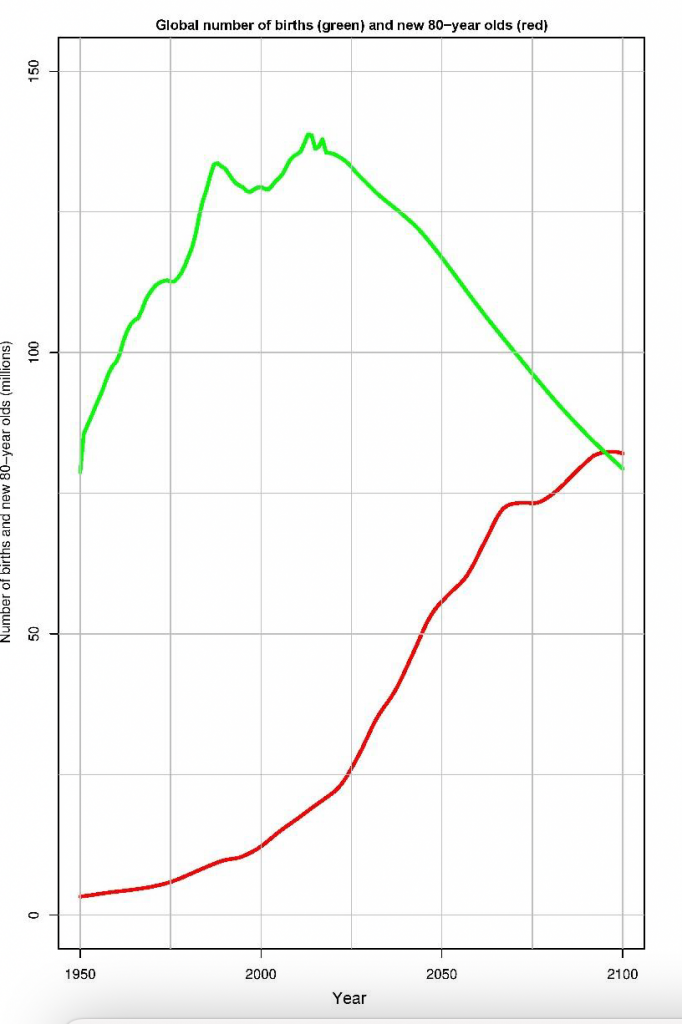

Population Decline

Rates of world population growth peaked at just over 2% a year in 1968, have declined since to about 1%, and are projected to drop precipitously to 0.1% by 2100. The time lag between rates of growth and actual populations means that world population is still rising, but the following graph, based on UN projections, suggests that the global population will gradually slow and stabilize at about 10.9 billion in 2100 as birth and death rates come more or less into balance and the global demographic transition is completed.

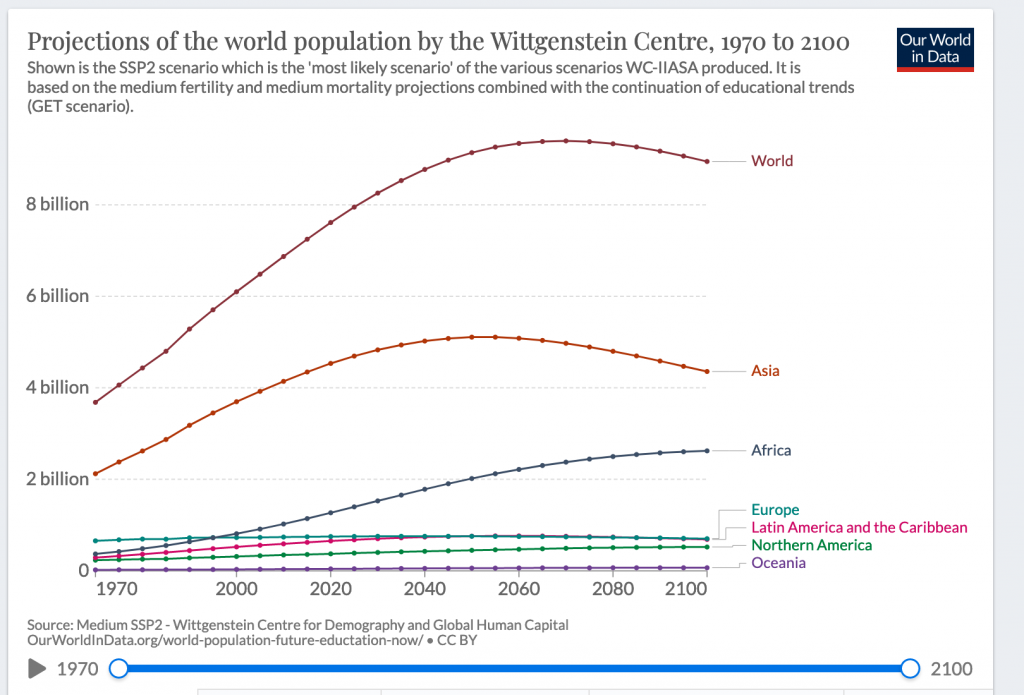

Two other population projections offer a different view. The Wittgenstein Centre takes into consideration improved levels of contraception, female education and fertility rates, and suggests that global population will peak at 9.4 billion around 2070 and then begin to decline because of pronounced drops in Asia, though these will be partially offset by continuing increases in sub-Saharan Africa until the end of the century.

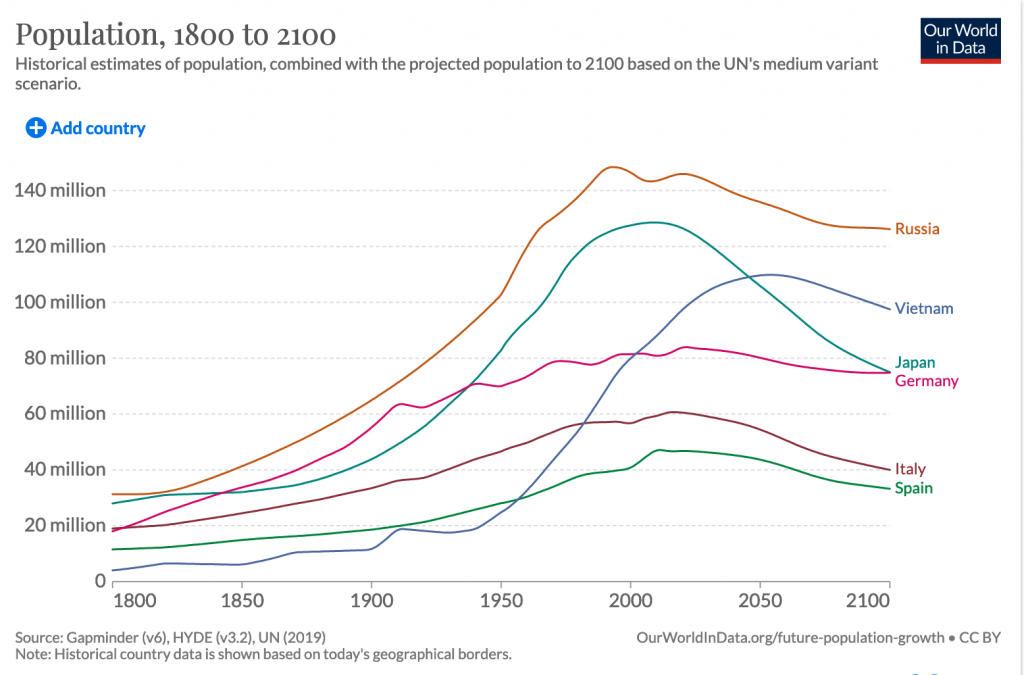

The apparently gentle curve for global population decline masks what are likely to be substantial changes for individual countries, as indicated below. Populations in China, Russia, Japan, Italy and Spain are already beginning to shrink, and Germany and Vietnam will soon follow.

A third population projection, published in The Lancet in 2020, forecasts even earlier and greater levels of decline than these graphs show. It anticipates that global population will peak in 2064 at 9.7 billion, and then fall to 8.8 billion by 2100. More specifically, it suggests that populations of 23 countries will decline by about half over the course of this century. These include Japan (128 million to 60 million), China (1.4 billion to 732 million), Spain (46 to 23 million; Italy (61 to 31 million).

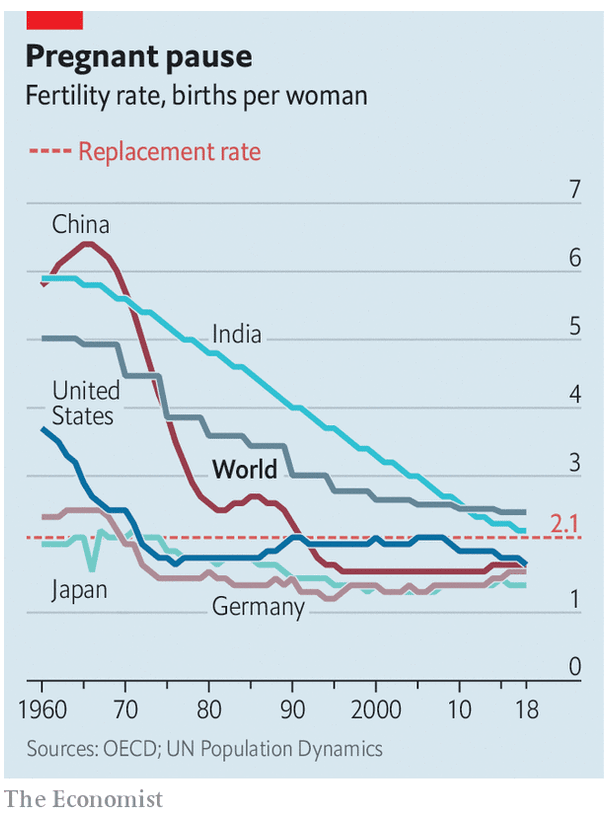

The reason for these steep declines, revealed in tables accompanying the article, is that total fertility rate, the number of children born per woman of child-bearing age, has already fallen well below the replacement level of 2.1 in those countries, and indeed in every country in Europe and North America. India and Latin American will soon follow, and by 2100 only a handful of countries will be sustaining their population. The authors of the Lancet article do not expect fertility rates to recover to replacement levels.

Consequences of Population Decline

The consequences of global population decline are half a century or more in the future. But for some countries declines are already underway, and within one or two decades will amount to reductions of many millions. It is not entirely clear what the consequences of this scale of population loss will be. It has been argued by some that fewer people should mean a reduction in environmental impacts, less congestion, and higher wages because there well be fewer people working. However, if GDP per capita continues to grow in spite of population decline, then environmental impacts could actually increase because wealthier individuals have larger environmental footprints than poor people. Moreover, there are strong indications that urbanization is increasing even as populations decline, which means that congestion in cities is unlikely to diminish. And some economists have made a compelling case that lower fertility rates are associated with growing economic inequality because inherited wealth is concentrated among fewer children.

If GDP per capita does not continue to grow at a rate that can offset the loss of population, a falling tax base will lead to a decline in basic services, and probably reduced technological and other innovation because that usually come from the young. But if GDP per capita continues to grow faster than the decline in population, as it has recently in Japan, standards of living will actually improve as populations fall.

The authors of the Lancet report think that shrinking and aging populations will pose substantial economic problems as governments struggle to cope with smaller working age populations and fewer taxpayers to provide funds need to meet the growing needs of the elderly, including health care and pensions. Some countries, such as Canada, are expected to continue to maintain or grow their populations through liberal immigration policies, but in others “the desire to maintain a linguistic and culturally homogeneous society will outweigh the economic, fiscal, and geopolitical risks of declining populations”. In other words, population decline could lead to intensifying nationalist and exclusionary political views.

Charles Jones, an economist at Stanford, has made what thus far seems to be the most sophisticated theoretical investigation of the economic impacts of declining populations. In his paper “The End of Economic Growth?” he pursues the idea that in many economic growth models the size of a growing population plays a crucial role because it leads to the growth of new ideas. When he introduces population decline (he refers to it as “negative growth”) into these mathematical models, the result is that innovation and the stock of knowledge stagnate and economic growth grinds to a halt. His conclusion is that if this happens standards of living will stabilize at a reasonably high level, but the population will continue to fall.

At least one commentator, Robert Harding in the Financial Times, suggests that in fact these processes may already be at work in Japan where, even though GDP per capita has risen, almost all recent income growth for working people has been soaked up by tax rises and higher house prices, factors that suppress fertility and therefore contribute to the ongoing population decline.

Under such conditions it will become increasingly difficult to maintain infrastructure and services such as public transit, first as individual buildings are abandoned, and then as neighbourhoods and rural communities become increasingly deserted. Unless the drop in fertility is offset by immigration from places where populations continue to expand, the enormous legacy of built environments created for peak populations will become a growing burden for aging and smaller populations.

The Costs of Climate Warming

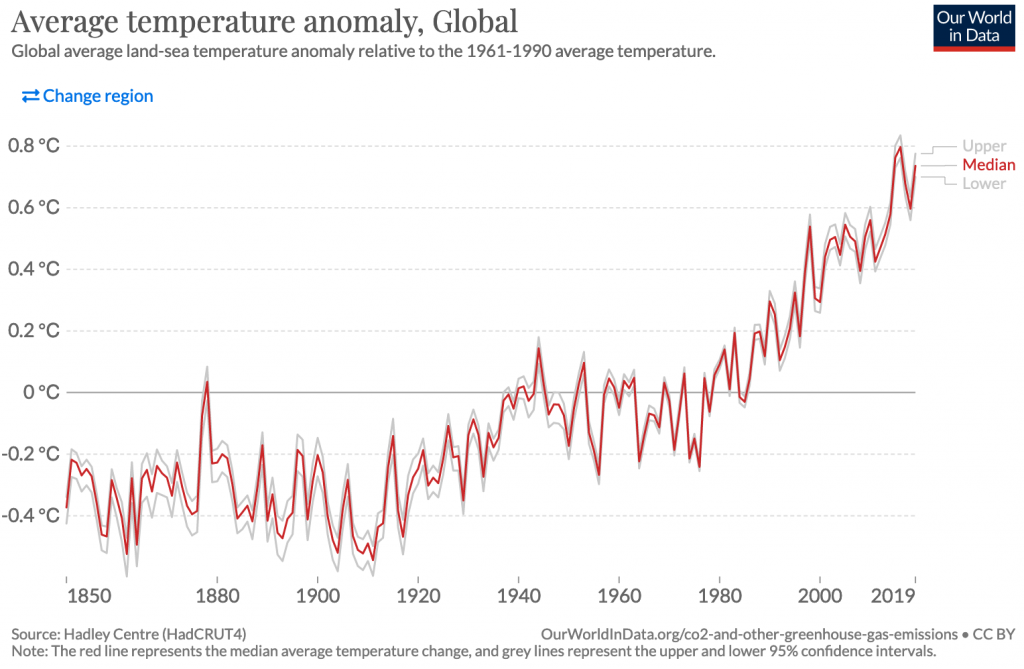

Since the 1980s it has become obvious that treating the atmosphere as a convenient and free way to dispose of CO2 emissions has contributed to a steady rise in global mean temperature. This has serious implications for causing changes in climate and weather, especially extreme weather, for the rest of this century and beyond.

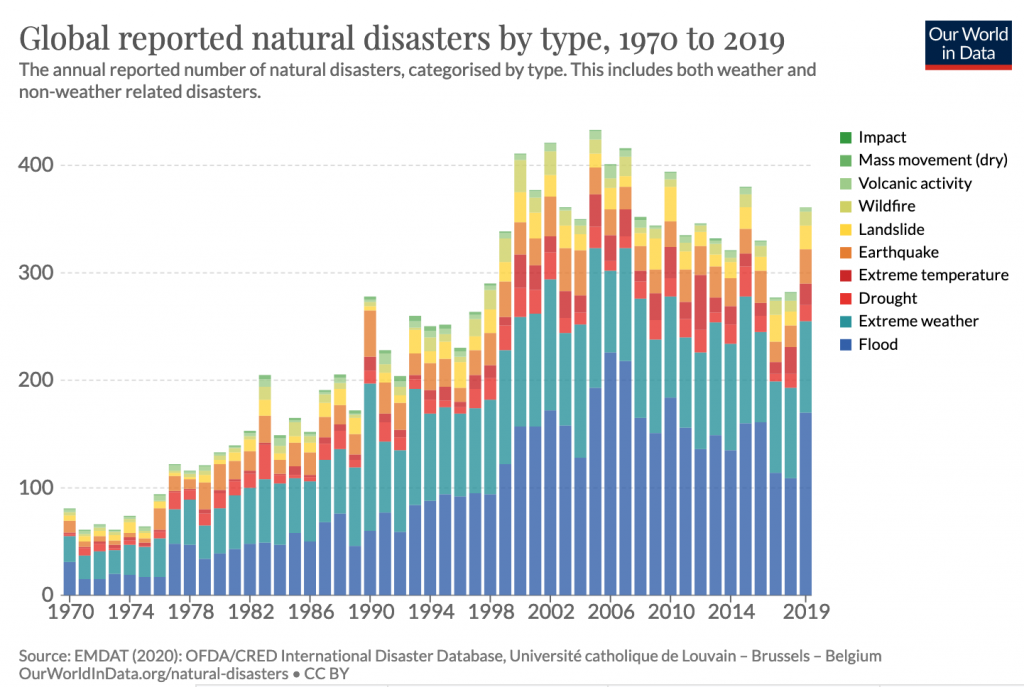

I will begin this consideration of the costs of climate change with evidence of recent trends in natural disasters.

In spite of this increase, since 1970 there has only been a modest increase in the number of annual globally reported natural disasters (especially floods and extreme weather), and suggestions of a slight decline since 2006.

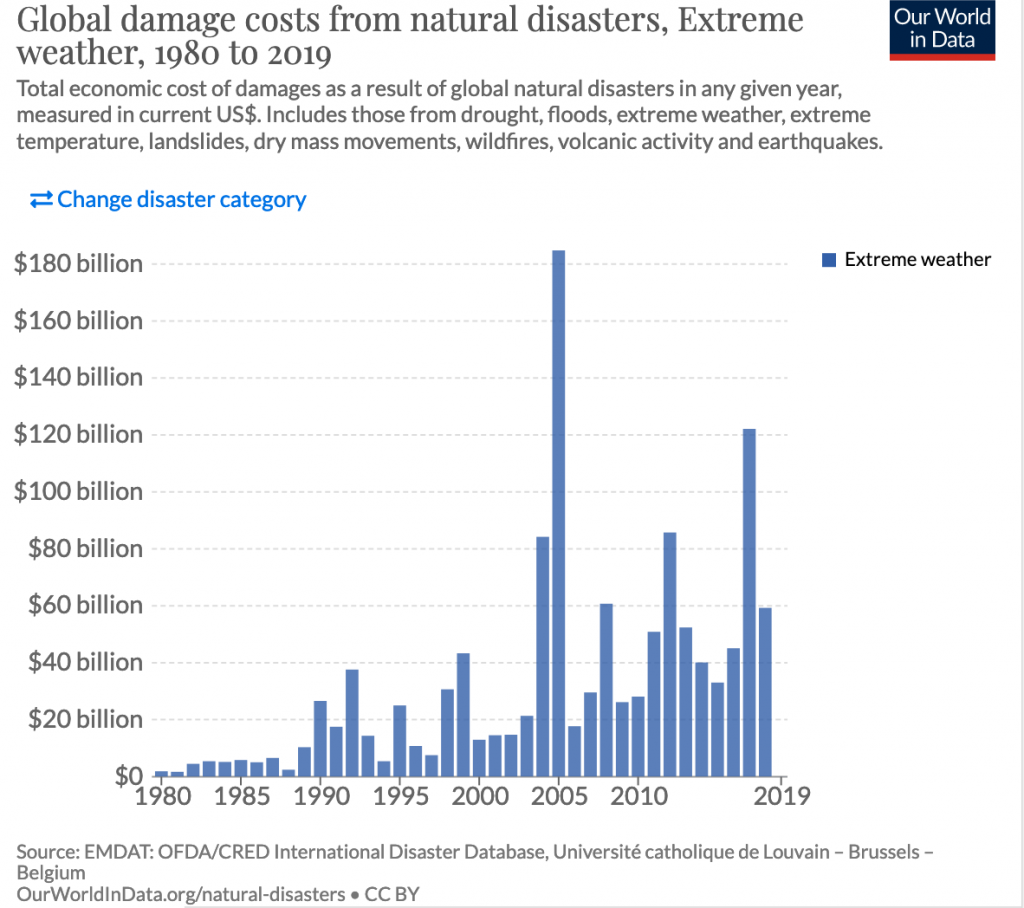

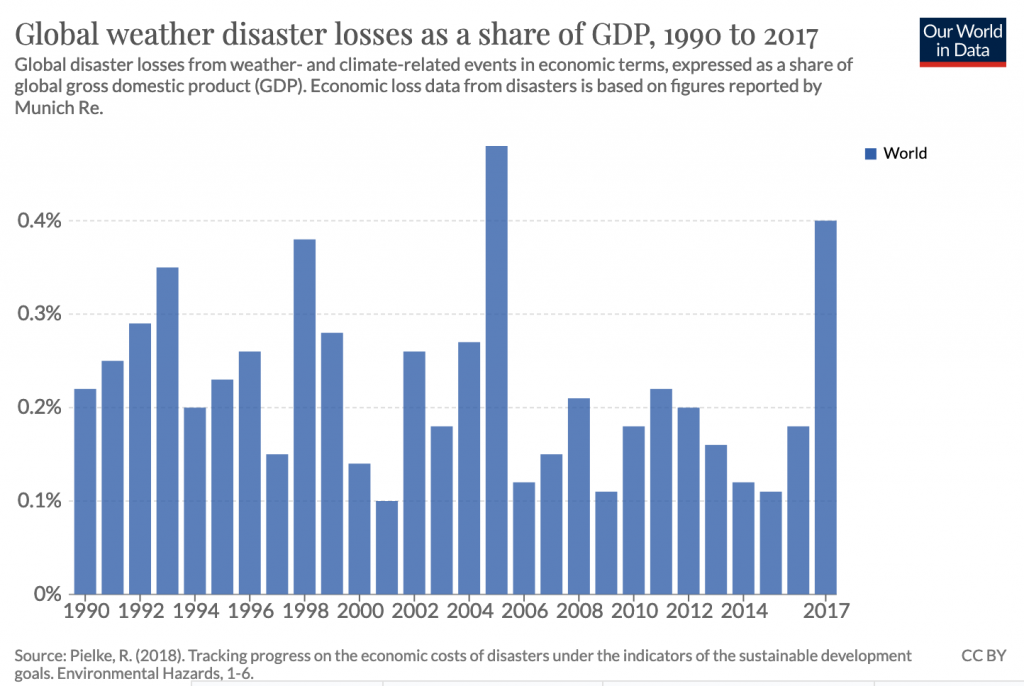

Global damage losses from extreme weather, also suggest an upward trend, but if those are considered as a share of GDP this is not the case, presumably because GDP has grown at least as quickly as those losses. On average about 60,000 people a year die from natural disasters, about 0.1% of all deaths.

However, these data on economic losses have to be interpreted carefully because there is confusion in the way losses from weather disasters are calculated, and there is a tendency to underestimate long-term effects (Botzen, Deschenes, Sanders, 2019). Nevertheless, it seems to be the case that, although natural disasters get national and international media coverage, their economic losses tend to be regional and fairly short-lived. In smaller nations, such as those of the Caribbean that are prone to major hurricanes, impacts on GDP may still be substantial, and have a significant opportunity cost because funds used for reconstruction might otherwise have been used for development initiatives.

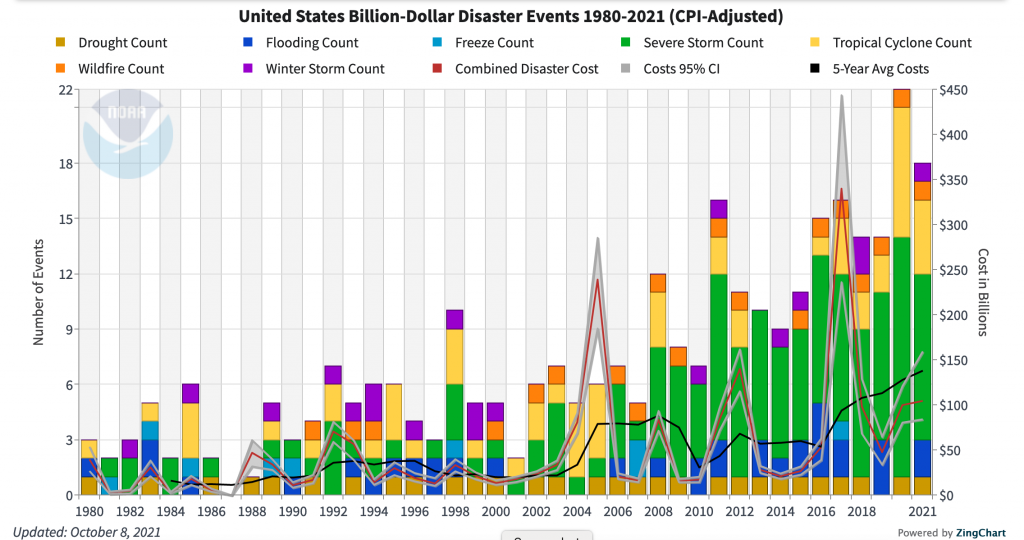

In countries with large diversified economies, such as the United States the costs of natural disasters are relatively minor (usually less than 1% of GDP, though in 2020 the $450 billion damages were about 2.25% of GDP, which was about $21 trillion). Nevertheless, they are a growing concern. Detailed records of the costs of major disaster events (by NOAA, shown below) indicate an upward trend. The number of events has grown from 2.9 in the 1980s, 5.4 in the 1990s and 6.3 in the 2000s, to 12.3 in the 2010s, and so far in 2020 and 2021alone there have been 20 major events. If this trend continues losses from climate related disasters will suppress annual growth rates in GDP, which have averaged about 3% for the last fifty years, and are declining in higher income countries.

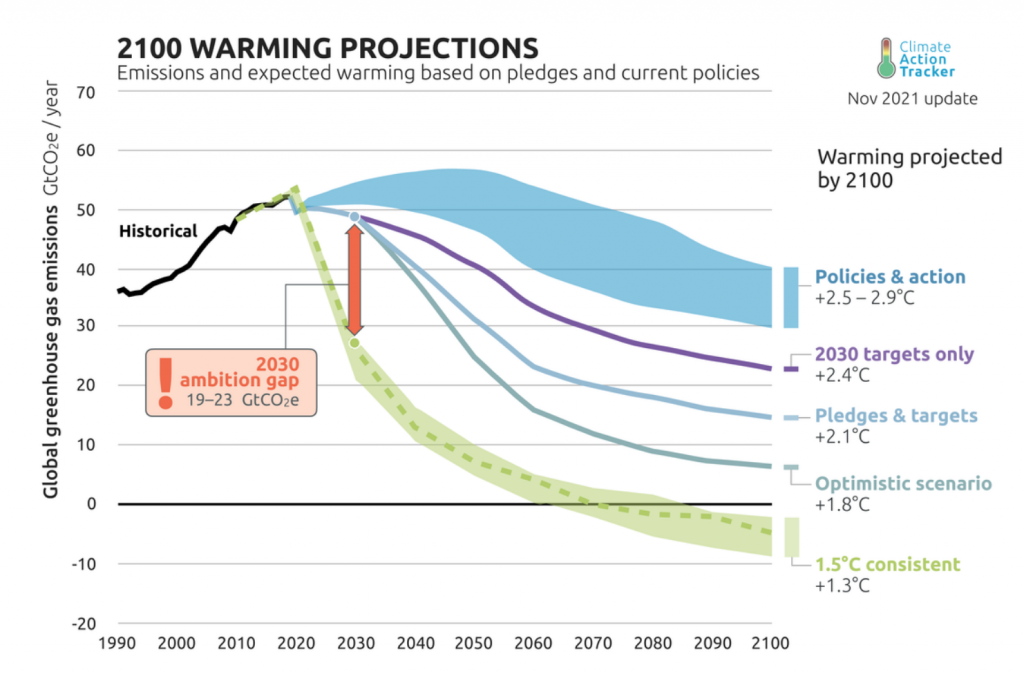

This trend also needs to be put in the context of projections of global warming. Global mean temperature has already risen about 1.2C above pre-industrial levels. How much further it will rise depends on mitigation measures and political will. The most optimistic outlook, according to Climate Action Tracker in November 2021, is an increase to 1.8C, but current policies and actions suggest something closer to or more than 2.5C. Increases of these magnitudes could lead to catastrophic losses from extreme weather in many regions of the world.

This, together with the evidence that temperatures and CO2 concentrations are greater than they have been in human history, indicates that recent trends of the number and costs of weather related environmental disasters offer few guides about what is to come. It is inevitable that the costs of dealing with climate change will climb rapidly and possibly exponentially, not only because of the damage they will cause, but also because of the transformative changes required to move closer to net zero, and because of the need to implement adaptations to handle more extreme weather that will include major expenses such things as protecting cities from rising sea levels and relocating climate refugees. It is possible that growing costs of weather disasters could almost negate annual growth in GDP.

Does this mean the end of economic growth?

When I began to think about the relationship between economic growth, population decline and climate change, my assumption was that the costs of coping with climate disasters, coupled with steadily aging and shrinking populations would be huge brakes on economic growth. However, what I have learned is that is not necessarily the case. It seems that economic growth has broken free of population growth, and one of its main drivers is now innovation, which can allow GDP per capita to be maintained even as populations decline. And it seems that the economic costs of natural disasters, at least in large diversified economies, thus far have amounted to a small percentage of total GDP, and the reconstruction following those disasters can count as contributions to GDP. While this percentage will grow in the future, I have found no indications or opinions that climate change, alone or in combination with population decline, will bring an end to overall economic growth and increases in per capita GDP.

However, from the perspective of particular places matters look rather different (as I have discussed in previous posts here and here). In some regions of the world, rural communities, small towns and even cities, face a future that involves a combination of slowly withering away as people age and the young move away, and the possibility of acute disasters of heatwaves, droughts, floods, and wildfires. Economies may continue to grow, but over the next hundred years geographies will change dramatically and everyday life in places everywhere will become more challenging.

[An afterthought, two days after posting this. I can’t help thinking that I have understated the possible impacts of the combined effects of population decline and climate related disasters, which could be much greater than the sum of their parts. The evidence so far is that a modest drop in population may be offset by innovation that results in growth in GDP per capita, and on average the costs of weather related disasters may only be a small percentage of GDP. But as populations drop by half, and if the costs of disasters regularly come to exceed annual growth in GDP as global temperatures climb, matters could take a very different turn ].

[An update 02 June 2023. The Economist has a leading article today “Global Fertility has collapsed with profound economic consequences: What might change the world’s dire demographic trajectory?” This is, for The Economist, a rather breathless consideration of global population decline that will occur later this century, written as though it is something that has just become apparent even though their writers have frequently discussed the current declines in Japan and Italy and elsewhere. It includes the remarkable comment that “The world is not close to full…” without any supporting argument, and argues, as the subtitle indicates, that we need to get population growth back on track in order to ensure economic growth (though it acknowledges that efforts in individual countries, such as Hungary and Singapore, to boost higher fertility have failed). Environmental concerns are blithely dismissed (“Whatever some environmentalists may say, a shrinking population creates problems.”)

I think this leader fails to identify the profound and clear demographic indications that economic growth and economic theory for the last three centuries or so have been tied to population growth, and that population decline will require a radically revised approach to economics, and indeed how life will be lived. The key questions are: What will economics without growth be like? How will economic systems, and for that matter urban planning, adapt to shrinkage? What will be abandoned and what retained? Or, from my perspective on place, how can places be adapted to an abundance of stuff that is no longer useful – empty houses, abandoned neighbourhoods in cities, expressways and airports and container ports that will be far too large for future needs? This may seem like the stuff of science fiction, but it’s probably less than fifty years away.]

These shifts are the context for

These shifts are the context for