This post is a summary of some ways place has been discussed in literary criticism that may have relevance for a broader understanding of place experience. Though it refers to a few books that are often considered to be based in particular places (such as Thomas Hardy’s Wessex novels, or Thoreau’s Walden) it is not a review of them. It is really just a synopsis of interpretations about the role that place plays in literature that I come across and think are interesting. It elaborates remarks I made in previous posts on writing about places, and Islandia (a novel that is about sense and love of place)..

Place as Context or Background

The most straightforward use of place in fiction is as a background to a story. William Zinsser puts the matter neatly: “every human event happens somewhere, and the reader wants to know what that ‘somewhere’ is like” (p.88). This is so even the place has nothing much to do with characters or the plot. A simple description of the setting , perhaps done in broad strokes in the first few pages, allows readers to fill in details with what they know from their own experiences or knowledge of real places. Something similar is done in movies and TV series, often with little more than a place name and a few shots of landscapes.

In this sense place is a backdrop, not unlike stage scenery, that has minimal significance for the story or the characters involved in it.. The story could happen almost anywhere, but the place where it happens provides a bit of incidental colour and interest.

Place Integration and/or Metaphor

This is a more sophisticated literary use of place, in which it serves a symbolic role that embroiders the story. Linn Ullmann, a Norwegian writer (who I cited in the post on Writing about Places) suggests: “Before you can write a good plot, you need to write a good place.” To support this contention she refers to a comment in a story by the Canadian author and Nobel prize winner Alice Munro: “Something had happened here. In your life there are a few places, or maybe only one place, where something has happened. And then there are the other places, which are just other places.” The settings where something happened are where meaning resides and they contain and embroider the story and amplify the characters. In effect, for writers such as Munro without a place there is no story.

Leonard Lutwack discusses place in more literary terms in The Role of Place in Literature. He takes a broad definition of place as “all inhabitable space,” which includes all forms and scales of scenery, setting and location, and considers the various ways the particular identities of these have been used throughout the history of literature in order to reinforce personalities and plots. He pays considerable attention to the rhetorical and metaphorical purposes place can serve.

Regardless of whether places in works of literature are rooted in fact or not, Lutwack’s view is that they serve a symbolic function. He argues that a core element in much American writing in the 19th and early 20th centuries were the distinctive places and regional settings that provided challenges and opportunities. Since then there is evidence of increasing placelessness in literature associated with the implications of dislocation, disorientation, detachment from home and the restless mobility of modern life. Lutwack also notes “If there is any place at all in the lives of this new breed of character,” he writes, “it is the highway itself.” p 227

This is, however, often ambivalence in this place:story relationship – bucolic landscapes do not necessarily mean mellow personalities, and undifferentiated spaces do not always mean placelessness. Virginia Woolf, for example, wrote in a celebratory tone of the anonymity and whirling flow of the city.

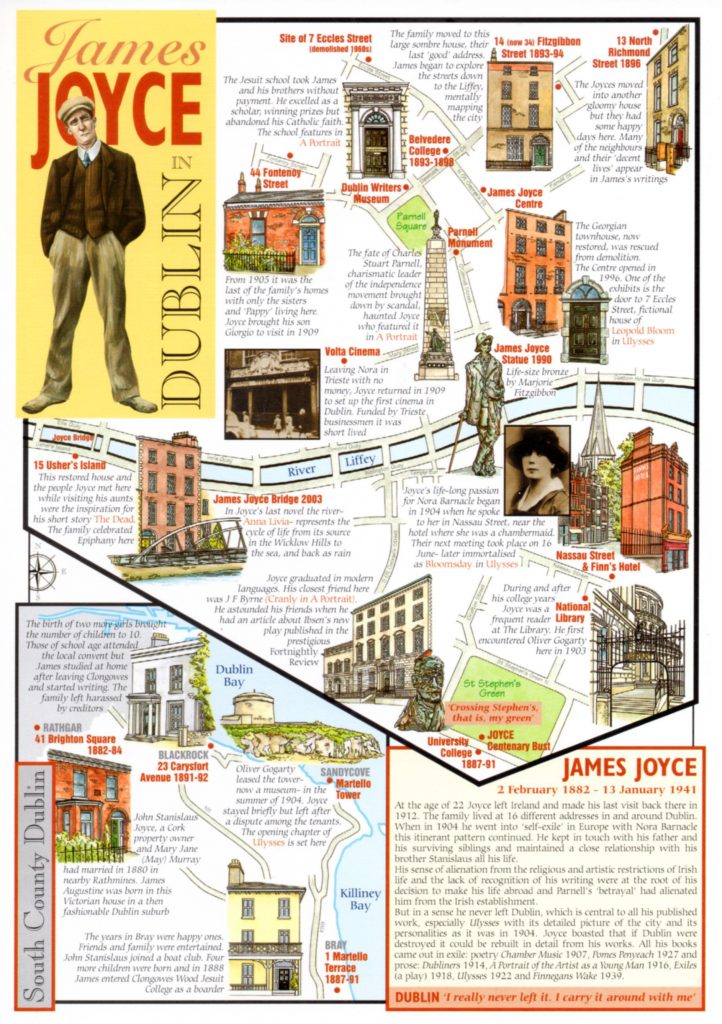

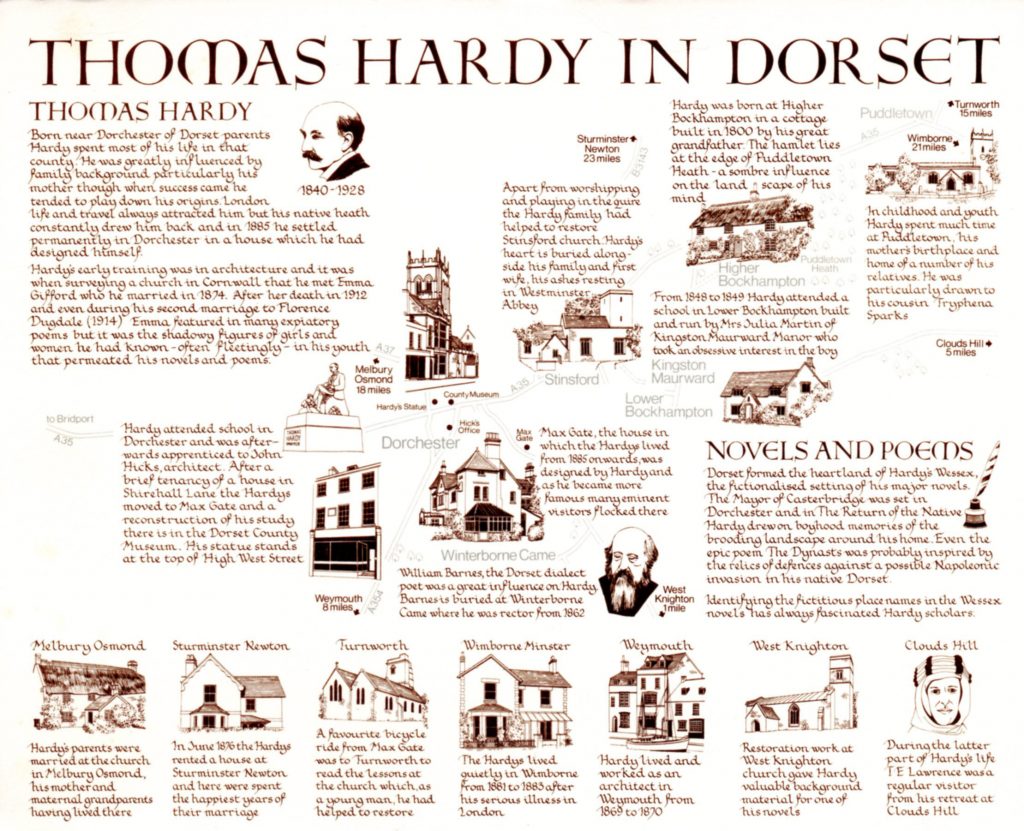

Place is also integrated into literature in more immediate ways that have to do with the author’s own experience of places either as a record or an invention of human experience. Jason Finch indicates that fiction of the English author E.M. Forster approximated real places, in some cases where he had lived, yet they were modified and given different names. Thomas Hardy did much the same in his novels of Wessex, in some cases using real places, and sometimes substituting invented place names for otherwise recognizable places – thus Oxford he called “Christminster.”

Jeffry Herlihy-Mera notes that Hemingway’s novels depend on the displacement that expatriation provided him. The places in which they are set are principal components of the narrative. Yet while Hemingway had lived in them, he always wrote about them when he was living elsewhere, a role he explicitly referred to as “transplanting” – he needed some distance to capture through his memories the traits he regarded as valuable for his writing. Incidentally, Hemingway also evaluated and esteemed the places where he worked “Madrid was always a good place for working,” he wrote. “So was Paris, and so were Key West, Florida, in the cool months; the ranch, near Cooke City, Montana; Kansas City; Chicago; Toronto; and Havana, Cuba. Some other places were not so good but maybe we were not so good when we were in them.” (cited in Herlihy-Mera, p. 56-7).

Circularity

While particular places often inspire authors, who then incorporate those into their stories with some fictional elaboration or modification, the relationship between places and literature often can involve a sort of circularity between places, authors, readers, authors and places.

Biographers of authors and artists almost always explore the personal landscapes of their subjects, where they grew up, where they chose to live, because without knowing the places that have mattered to them, biographers can’t form a complete sense of their work. Childhood environments, places and memory all are aspects of the foundation of prose and poetry.

In addition, novels, movies and works of art can shape how we see and interact with the places where they are set. The American writer Walker Percy wrote a novel The Moviegoer that is centred on a character for whom a place only became truly real when he had seen it in a movie. A rather version of this reinforcement occurs in literary tourism that involves visits to the places where authors once lived, or wrote about, and have in some cases have been rebranded to celebrate their fictional identities. Shakespeare and Stratford-Upon-Avon; the Globe Theatre reconstruction in London; Hobitton, which was built as a set for the movie of the Lord of the Rings and is now a tourist attraction in New Zealand. More broadly, but less easy to illustrate, is the effect fiction has on popular interpretations of places and landscapes. It is difficult, perhaps impossible, to visit Walden Pond without seeing it through the writing of Thoreau.

There are also instances in which authors engage with the real places in which they have based their stories. Jason Finch observes that the rural part of Hertfordshire in England that was where the writer E.M. Forster had lived in childhood, and which he represented in fictional form in his novel Howard’s End, is also where the first post- Second World War new town of Stevenage is sited. After spending several decades elsewhere Forster returned to Hertfordshire during the war, and despised and actively protested the plan that was being prepared for Stevenage as “a meteorite town, fallen from a blue sky” (Finch, p.384) created by “plansters” and unwelcome intruders (Finch, p.395).

Place as Nature and a Moral Imperative

Barry Lopez, a widely admired author of novels and non-fiction works about nature and environment, wrote a short essay “A Literature of Place” in which he suggests that there is a long tradition in American writing about “the impact nature and place have on culture.” This tradition includes Thoreau, Melville, Steinbeck, Faulkner, Wendell Berry and Gary Snyder. For Lopez the literature of place is a genre that has to do careful observation of the particular qualities of natural environments, and then explicitly raises questions about technological progress and modern economic development that threaten these natural places.

In his essay Lopez argues that to write about a place in this sense requires that you become intimate with its history and that in effect you establish an ethical conversation with it about what is a good or bad way to treat it. In other words the literature of place reflects this intimacy and involves a moral imperative to protect it and protest how it is threatened.

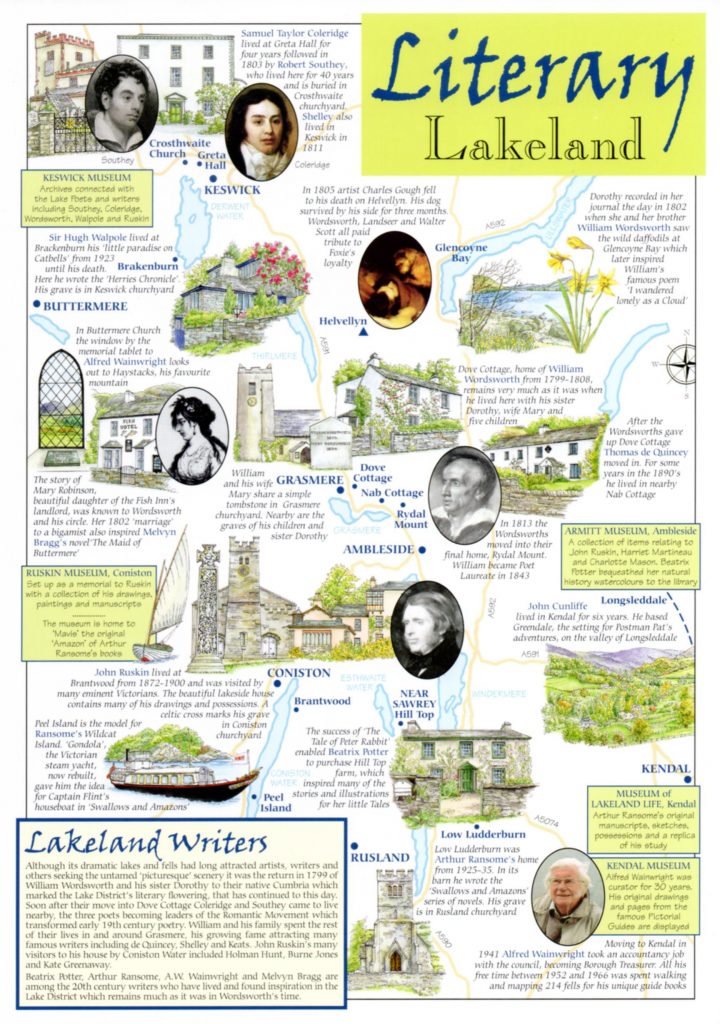

This moral imperative probably originated with the Romantic movement. It was, for instance, part of the association between landscape and literature for those who lived in and wrote about the Lake District in England. “The world is too much with us,” William Wordsworth wrote in 1807 as the Industrial Revolution gained momentum. “Late and soon, getting and spending we lay waste our powers. Little we see in nature that is ours.”

Place in Literature as Parochial, Exclusionary and without Historical Perspective

Roberto Dainotto in Place in Literature: Regions, Cultures, Communities offers a rather different and more academic argument. He is critical of the role of the conventional interpretation of place in literature because “it is fundamentally a negation of history.” It is tied to regionalism, which is “the idea of place as a fixed background of human sensibility” and assumes that places have their own positive, local traditions., which are mostly divorced from social and economic history.

Implicit in literature that celebrates place, he suggests, is the idea that different place traditions are the basis for happy coexistence. “The goal posited by the literature of place “is therefore an ethical one: to replace the ‘insufficient’ historical remedy with the geographical cure – a cure that…will let tradition survive and be honored, sheltered in the boundaries of place” (p.14). Issues of class, power and political economy, which Dainotto from his political economics perspective regards as primary, are mostly ignored if not suppressed. According to his interpretation the literature of place is exclusionary, inward looking, avoids the realities of social change, technological progress and political struggles.

He supports this with interpretations of Thomas Hardy, D. H. Lawrence and the philosophical writing about home of Martin Heidegger. These represent place as free from the contingent imposition and crises of what know as history. For instance, in Hardy’s Return of the Native each main character is the personification of a place, and it is set in the fictional rural region of Wessex in the 1840s and 1850s where there are no railways or evidence of modernity, and distant cities are filled with vice and corruption.

Dainotto acknowleges that “nations are monstrous inventions, with a tendency to violence”, (p.169), but his view is that the literature of place with its “archaic and more pervasive dream of placeness” presents a much more more serious problem because it can, as Heidegger’s roots in and celebration of peasant life in the Black Forest demonstrated, lead through rural regionalism to fascism. (See the post on Power and Place for some discussion of this criticism of Heidegger).

Dainotto’s critique of place is broadly consistent with the thinking of others, such as Doreen Massey, who have taken a rather narrow interpretation of place as bounded, permeated by tradition, and anti-urban, and then condemned it for being parochial and exclusionary. Though examples of this view of place can certainly be found in literature, it is a selective interpretation. There is also a literature depicting societies that are so caught up in universality and equality that they negate place, including Zamiatin’s We and Huxley’s Brave New World, with the consequence that they promote placeless forms of authoritarianism.

My view is that the best way to understand literature through the lens of place is to consider the ways in which it reveals the often ambivalent tensions between what is local and specific, and what is universal or widely shared. In this view, which is I think is widely represented in works of fiction, events and lives in particular places are inexorably caught up in processes of historical and social change.

References

Dainotto, Roberto, 2000 Place in literature: regions, cultures, communities, Ithaca, N.Y., Cornell University Press.

Finch, Jason, 2011 E.M. Forster and English Place: A Literary Topography, Abo Akademie University Press, Finland

Herlihy-Mera, Jeffrey, 2011 In Paris or Paname: Hemingway’s Expatriate Nationalism, Amsterdam: Rodopi (see especially Chapter 2 “The Role of Place in Literature’.

Lopez, Barry, 1997 ” A Literature of Place,” University of Portland, Portland Magazine, Summer 1997. Available online here

Lutwack, Leonard, 1984 The Role of Place in Literature, Syracuse University Press.

Ullman, Linn in Joe Fassler, “Before you can write a good story your have to write a good place”, The Atlantic April 2014. Available online here.

Zinsser. William, 1990 On Writing Well, Harper and Row.