It is fashionable to extol things that are local, for instance small businesses and locally-grown food. The word local and the term locality have meanings that derive from the Latin ‘locus’ which means place, and in everyday language these are more or less synonymous with place. Localism, which also is undergoing a surge in popularity, refers to social and political philosophies that give priority to local control to attitudes and practices, which is to say to approaches that champion places.

Inexplicably, the ideas of local, locality and localism have been scarcely mentioned in discussion of place. This post is my initial, cursory attempt to redress that, though I suspect it only skims the surface. I pay particular, critical attention to issues associated with localism because that seems to offer possible ways for implementing ideas about the fundamental role of place in our experiences of the world and also possible ways that will reflect the worst aspects of place.

Local

There is little about the importance of the local that is new, except that it is now in part a matter of choice, whereas for most people for most of human history it was an unavoidable fact of life. Food once had to be grown locally and distributed through local markets. Building materials mostly had to from nearby because there was no easy, inexpensive way to move them long distances. Most people lived their lives in small territories and spoke with local accents in regional dialects. This deep engagement with and dependence on whatever was local has been progressively eroded since the early 19th century, first with trains and the telegraph, and more recently with motor vehicles, air travel, television, and all the other innovations of modern communications that have facilitated placelessness.

Since about 1970 resistance against the erosion of place identities has grown, and the merits of choosing and protecting whatever is local have been advanced through heritage preservation, the revival of farmers’ markets selling local produce, the recognition of the need to attend to the idiosyncracies of local ecosystems, and the use of locally sourced building material in sustainable development and design. The idea of the local is now widely celebrated.

Two cautions need to be made about this . The first is that ‘local’ is a convenient and appealing term which evades precise geographical definition. It can be applied to a neighbourhoods, a town or city, a region or even a state or province. The only consistencies seem to be that the local is something that is less than nation-wide and certainly not international in origin or scale.

The second caution is that, paradoxically, a preference for things local is a widespread and international movement. A Google search for websites and images advocating the local reveals instances from across North America, in Britain, New Zealand, Mexico and Europe. Totally-locally is a British company, developed by Chris Sands who describes himself as a “branding person, place maker, marketeer,” that offers grass-roots, open-source local branding and has provided advice to many different places in Australia, France, Austria, North America and Ireland as a basis for improving local economies.

Localism and Subsidiarity

Localism refers to political and social philosophies that emphasize the local (meaning something less than national or global) in history, culture and identity. There are several versions of localism, including some inspired by socialist ideals or bioregionalism, and others deriving from the conservative dislike of central government.

These all embody, at least implicitly, the principle of subsidiarity, a notion explicitly promulgated by the Catholic church in the 1890s which proposes that practical issues should be dealt with at the most immediate or local level consistent with their resolution. Subsidiarity may have been part of the spirit of the times because contemporary arguments from an entirely unrelated direction were made in 1899 by the geographer-anarchist Peter Kropotkin in his book Field, Factories and Workshops of Tomorrow. He proposed that, in a world faced with scarcity of resources and a superfluity of labor, work should be where people live, workplaces should be small enough to be created without much capital, and production should be mainly from local materials and for local use.

Subsidiarity is a notion that has echoed through the thought of those with reservations about central government, including the famous urbanist Jane Jacobs, who wrote in her last book, Dark Age Ahead (p.103), that: “Subsidiarity is the principle that government works best, most responsibly and responsively when it is closest to the people it serves and the needs it addresses.” In other words, government works best at the small scale of local places, of neighbourhoods and cities.

Problems and Possibilities with Devolved Localism

Subsidiarity has a mixed history of success, especially when it is associated with attempts by higher levels of government to devolve responsibilities. In the U.S. during the Great Depression President Hoover put faith in localism, and implemented policies to resolve poverty and unemployment by encouraging relief and aid to be provided through what he expected to be creative initiatives at local levels. However, towns and states simply did not have the resources to accomplish this and in the end direct federal actions were required.

A more recent attempt at downloaded localism was made in Britain in 2011, when the Localism Act of Parliament set out a series of measures intended to transfer power from central government to local authorities and communities. A 2018 commission on the future of localism by a lobby group appropriately called Locality and which coordinates 550 local community groups, found that this legislation had, in fact, achieved no substantial devolution of power to localities. The commission commented that, among other things, the creation of successful local communities based on strong relationships between local government, citizens, and local businesses that share a commitment to place, requires the disruption of existing political hierarchies.In other words, localism cannot be achieved simply by some form of downloading.

A rather different interpretation of the effects of the Localism Act (comes from the Royal Society for the Encouragement of the Arts, Manufacture and Commerce. This British group is interested in how culture and the arts are embedded in local identity. It maintains that the devolution of political power in Britain is, in fact, gathering pace, and argues that in this context a richer understanding of place-based identity and local distinctiveness is more essential than ever. In a number of reports the RSA explores what it refers to as “the place-based dimensions of inclusive growth” with particular attention to economic assets and how these can adapt to structural economic changes and unequal growth. It also advocates that a well-informed picture of heritage resources at a local level is needed to inform place-making and place-shaping initiatives.

Grassroots Localism, Small Business and a Global Vision

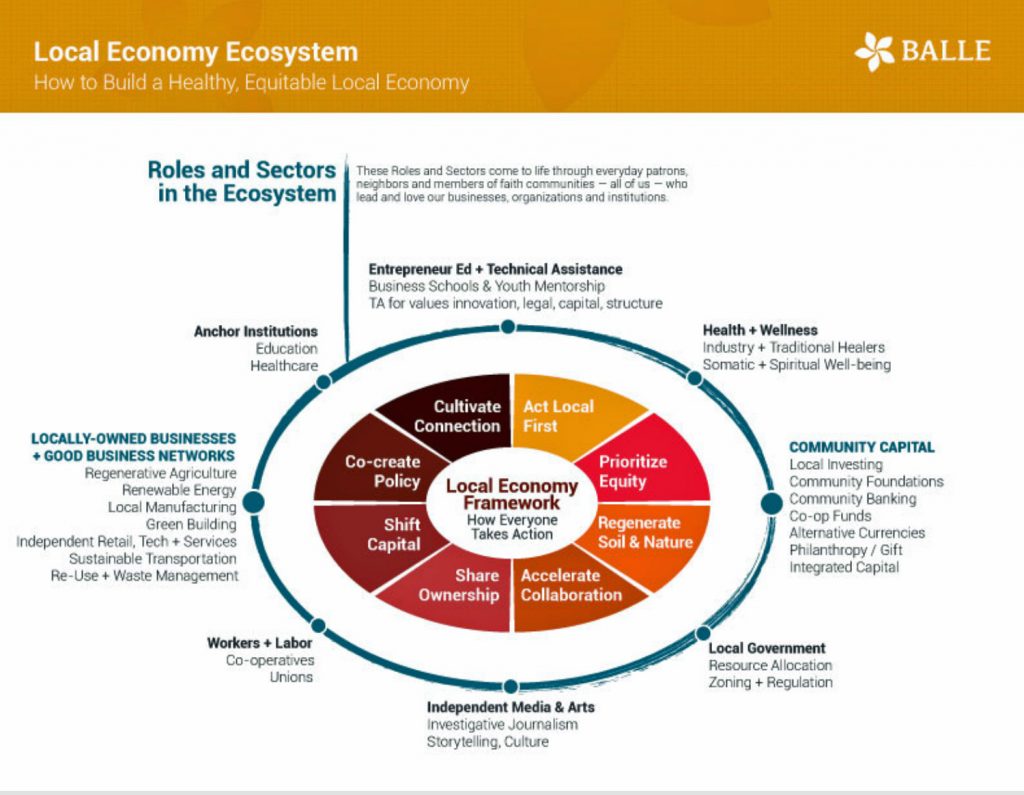

In North America recent advocacy for localism has followed a different course. For example, the Business Alliance for Living Local Environments (Balle) was founded in 2001 as a grassroots organization that could support small businesses and the possibilities they offer for the sustainable use of environments and sustainable local economies. Balle is now networked across 43 states and provinces in the US and Canada, and has connections with over 150,000 small businesses.

In effect, Balle is challenging the intrusions of national and international businesses into localities.The diagram below, clipped from its website, illustrates its core principles about interconnections between locally-owned business, community capital, local government, independent media and arts, labor, health and wellness, anchor institutions and technical assistance.

A specific instance of how Balle’s initiatives can work is suggested by Re>Think Local, a non-profit collaborative based in the Hudson Valley in New York State. Its aim is to build businesses and communities that are local, healthy and sustainable. It also aims to influence public policy in support of a place-based, new type of economy. Importantly, it stresses that this has to be seen as part of a global vision. Its website declares that “each of us is crafting a piece of a larger mosaic – a global network of cooperatively interlinked local economies” – in which:

• ownership matters because local ownership means local accountability and better resiliency

• place matters because supply chain decisions that choose local resources – whether food, energy, finances, or services – engender respect for environmental and human resources in a place

• opportunity matters because local means being better off, with less inequality

• nature matters because all wealth comes from nature and part of the joy of life is to be in awe of the mysterious beauty of the interconnected natural world

• relationships matter because only through co-operation will we be able to rebuild local food distribution or make local renewable energy affordable.

The New Localism and Politics

At least one conservative American periodical suggests that localism used to be “a distinctive part of the conservative lexicon” and that “traditionalists have always defended the loveliness of the local community against the monstrous monolith of the state,” but has now been claimed by liberals on the left. Indeed, the sorts of initiatives represented by Balle and Re>Think Local (and indeed by Locality and RSA in Britain) are characterized by Bruce Katz and Jeremy Novak as The New Localism, the title of a book published by the left-leaning Brooking Institutions in 2018 (it is worth noting that the phrase “the new localism” has been used in book titles and sub-titles since at least 1975, so exactly what is new about it is open to question).

The new localism, Katz and Novak suggest, is emerging by necessity as a way to solve the challenges of modern societies – economic competition, social inclusion, diversity, and sustainability. While populism on both the left and the right exploits the grievances of those falling behind in the global economy, new localism addresses them head on. It is associated with a downward shift of power from national governments to cities and local communities, as well as horizontal shifts from public sectors of government to networks of public, private and civic actors, and global networks of capital, trade and information.

Something similar has been suggested from the conservative side of the political spectrum by the European Conservatives and Reformists Groups, a centre-right group involving local and regional politicians in the European Union. In 2018 this group held a “Localism Summit” focused on the fact that cities and regions are facing challenges such as digital transformation, urbanization, climate change, disasters, and an influx of refugees. It acknowledged that these challenges “are felt locally and resonate globally,” yet advocated greater localism and reduced central regulation, and proposed that decisions about these challenges should be taken as close to European citizens as possible (which is consistent with the principle of subsidiarity that informs many EU practices).

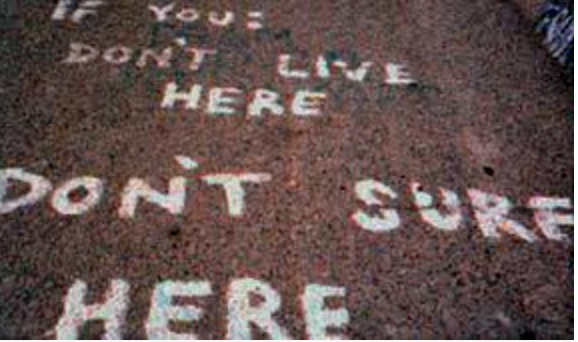

The fact that similar positions about localism are being advocated from the left and the right suggests that localism might offer ways to mitigate against the polarization that has become so apparent at higher level of government. It is, however, also the case that, as the photo of the Neo Localism installation above suggests, ideas of localism need to be approached carefully and critically. They can easily be co-opted by agencies and corporations that have little interest in anything local but find the language of localism useful for marketing. Alternatively, arguments for localism can be used to disguise discrimination against anything that is not local.

Localism and Exclusion

Simin Davoudi and Ali Madanipour, (in Reconsidering Localism, Routledge, 2015) point out that localism has both progressive and regressive paths. On the one hand it offers grassroots strategies for shaping sustainable, human-scale communities. On the other hand it can promote practices and attitudes that invoke a poisoned sense of place and exclusionary practices. In localism there is often an implicit sense that non-locals, people not like us, corporate chain stores, foreign products, are undesirable, their presence in a place needs to restricted, and the qualities and identities of places are best protected by those who consider themselves to be local.

One instance in which localism as exclusion of outsiders has become explicit is with surfing. In surfing the term ‘localism” refers to attempts to prevent outsiders from getting access to local beaches. As surfing has become an increasingly popular and international sport preferred surfing locations have become increasingly crowded, local surfers have come to see themselves as being displaced by outsiders, and have sometimes acted aggressively to keep the best localities for themselves.

Beaches with good surfing waves are comparatively rare, and excessive crowding destroys their value for everyone who wants to enjoy them. Localism as understood by surfers, it has been suggested, is a particular sort of response to a tragedy of the commons, the environmental tragedy that follows when individuals each try to get the best for themselves from a scarce but publicly accessible (or common) resource and the cumulative effect is to destroy the value of that resource for everyone. Something very similar is beginning to be apparent in anti-tourist protests in Venice, Barcelona and elsewhere. And on a global scale, climate change is a version of the tragedy of the commons in which the atmosphere is being treated as a free receptacle for greenhouse gases by almost all places in the world, all of which will experience the consequences of changes in climate and few of which show much determination to aggressively reduce emissions.

The regressive tendency to exclusion and to some version of the tragedy of the commons is always possible when the merits and needs of particular places are advanced over those of everywhere else. Resolutions to such problems requires policies and strategies that respond to the idiosyncracies of particular localities, yet transcend those places and are in some manner global in their scope.

Localism and Globalism

Localism and globalism are not opposed; they define each other. The benefits of locally based commitment and responsibility have to be tempered by acknowledging that what happens locally always in some way interacts with regional, national and international processes and responsibilities. This acknowledgement is apparent, for instance, when Re>Think Local (discussed above in the section about Grassroots Localism) makes it clear that its vision is one that sees the local as part of a larger mosaic in which all groups advocating localism are parts of wider networks and interlinked economies. It was also apparent in what Lewis Mumford wrote about the work in India of Patrick Geddes, one of the founders of modern planning, in the second decade of the 20th century : “If one part of his thinking was attached to the region, indeed to the village or hamlet, another was attached to the whole planet” (Lewis Mumford, 1947, “Introduction” Patrick Geddes in India, ed J. Tyrwhitt, Lund Humphries, p.9). If localism is to be considered a possible way to formulate a politics of place, it is essential that it avoids falling into the isolationist error of regarding a local culture or place as in any sense complete, final or self-sustaining, even as it celebrates the distinctiveness of places and the deep attachment of people to them.

Interconnectedness between localities, regions and the world as a whole cannot be wished away or shut out by walls and fences. The authority and responsibility of higher levels of government is needed to coordinate local practices, for instance in dealing with natural disasters or to combat climate change and economic inequality, and indeed in encouraging local sustainability.

From the perspective of politics, localism is not about replacing all levels of higher political authority with local ones, but about a shift in the balance of power, in effect adopting subsidiarity so that responsibility and effective decision making occurs closer to the problems that have to be resolved. It is about ensuring that place is always an important consideration in the formulation of policies and practices at all levels of government.

From the perspective of place, localism seems to invoke aspects of dwelling, of engagement with the world that invokes sparing, preserving and caring for the earth in its specific manifestations in places. Localism involves responsibility, both in the sense of taking responsibility for place and in the sense of responding to the character of place. It challenges tendencies to adopt generic, placeless solutions and offers a way to balance centralist abstractions and arrogance with the immediacies of places. At the same time it requires acknowledgment of philosopher Jeff Malpas’s description of place as an “open, cleared yet bounded region in which we find ourselves gathered together with other persons and things, and in which we are opened to the world and the world to us” (Jeff Malpas, 2006, Heidegger’s Topology: Being, Place, World, MIT Press, p.221, and also my comments in a separate post on this website).

As a positive politics of place localism must respond to the openness of every place, an openness that is grounded in the complex unity of somewhere particular, yet opens outward to the world even as it is open to the diverse political, economic and environmental processes that affect all places in the world.