Common preamble to three posts on changes to place over the last 50 years

I recently posted an unpublished and not previously circulated essay at Academia.org on the ways that places and place experiences have altered since about 1970. It draws on some of my posts on this website, and also on my publications about place (mostly book chapters that might not be easily available) since about 1990. My main reason for writing the essay is that experiences of being rooted in place, belonging, attachment and so on, and indeed the forces of placelessness that might be eroding these, are not timeless and unchanging. What made sense in 1970, when I was writing my book Place and Placelessness, needs to be updated both because there are now practices for protecting, making and promoting places that did not exist then, and because the ways places are experienced have shifted dramatically in a world of cheap air travel and omnipresent electronic devices.

I assume those looking at this website and those reading Academia are mostly from different audiences, so this and two additional posts offer a sort of point form summary of my Academia essay, which is about 60 pages long. This post (#3) offers some theoretical speculations about changing relationships between place and placelessness and what they portend for the future of places. The first post (#1) considers recent changes to ways places are made. The second post (#2) deals mostly with changes since 1970 to the ways places are experienced.

Although they are really only summaries of ideas, I hope that together the three posts offer enough suggestions about recent changes for you to be able to explore them further, perhaps question some conventional assumptions about roots and sense of place, or, conversely, to refine arguments that place provides continuity in the face of change.

Changing relations of place and placelessness

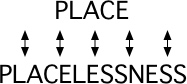

The forces of placelessness and the processes of place constantly push and pull against each other in ways that change over time. In Place and Placelessness I presented them as in opposition to each other, with placelessness eroding the distinctiveness of place. Something like this:

I subsequently began to regard them as in a dynamic balance, always pushing against one other. This interpretation, which regards everywhere as to some degree placeless, and in some ways distinctive, is both more flexible than the idea that place and placelessness are opposing forces. It also makes room for the recognition that a balance is necessary to offset situations where distinctive becomes associated with exclusion, or situations where uniformity is so extreme that identification with place becomes virtually impossible.

But even this sort of yin-yang idea of the relationship between place and placelessness fails to capture what seems to have happened with increasing mobility and the intrusions of electronic media. It does not reflect the complexities of hybrid places in mongrel cities, non-places, and the ways even heritage preservation has resulted in standardization. It now seems more appropriate to understand the relationship of place and placelessness as one of entanglement, at least partially. In some places distinctiveness is clear, elsewhere uniformity is clear, but it is also the case that non-places can be considered as distinctive places, World Heritage Sites can be overrun by mass tourism, the celebration of place can involve NIMBYism and exclusion, and the confusions of hybridity can contribute to complex and distinctive places. This simple diagram is an attempt to capture this blend of balance and entanglement:

Place as a lens to the world

There are many different ways to understand place, but one that I think has considerable methodological value is to regard it as a lens to the world. In other words, all places are microcosms of larger patterns and processes, albeit adapted to local circumstances, because they are the consequences of those processes and also contribute to them. Places are fusions of physical settings, activities and meanings that are parts of the whole world, and they are themselves wholes. It is in and through place, or more specifically through specific places with their own names, that we know the world. The wholeness of place is not something mysterious. It is what we experience everyday, at home, when we step outside, when we travel.

Given this fundamental relationship, the deliberate study of place and of places offers a means to understand the complex unity of the larger world as it is directly known and experienced, and the ways this world is changing. That said, given the heterotopian confusions of the present-day world this is not a straightforward process.

Trend to Heterotopia

Place, and the processes that give rise to places are not immutable. Fifty years ago, when I was writing Place and Placelessness, it seemed that local processes that had once led to distinctive places were being eroded by the abstract forces of modernism. This simple, binary interpretation does not apply well to many landscapes created since then in the light of heritage preservation, branding, mobility and electronic media, all processes that seem to simultaneously enhance yet undermine place identities.

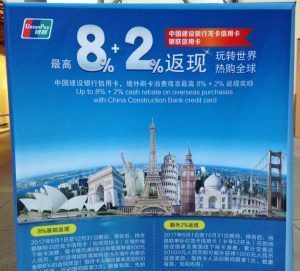

Two examples of present-day place confusion. On the left: Sense of Place clothing store is in the shopping mall underneath Kyoto Japan Rail Station. A sign in the store reads: “Sense of place is about confidence in knowing who you are and what style means to you.” On the right: a conflation of iconic skylines from world cities, on a sign entirely in Chinese in Seattle Premium Outlets, a discount mall on the Tulalip Indian Reserve, north of Seattle, where many of the shoppers are Chinese-Canadians.

Michel Foucault suggested the word “heterotopia” to characterize this confusion. A heterotopy is literally something out of place. In heterotopia most things seem out of place and it is difficult to identify any coherent logic underlying them. Old geographical notions about regions and settlements no longer apply. Everything everywhere is now interconnected, yet filled with unlikely juxtapositions and dislocated experiences.

This fragment of a streetscape in North York in Toronto is a mundane example of the unlikely juxtapositions of heterotopia. Roses New York offers a fusion of North American and Persian food, upstairs is an Egyptian psychic, next door a Korean-Japanese restaurant, the billboard advertises fictional places on Canadian TV.

This fragment of a streetscape in North York in Toronto is a mundane example of the unlikely juxtapositions of heterotopia. Roses New York offers a fusion of North American and Persian food, upstairs is an Egyptian psychic, next door a Korean-Japanese restaurant, the billboard advertises fictional places on Canadian TV.

Although heterotopia is not entirely new (unlikely juxtapositions have always happened whenever different cultures have come into close contact), in the last half century it has hugely intensified with multi-centred living, mobility and transnationalism. What is remarkable is that, not unlike electronic devices, it has so quickly become familiar and taken for granted in the mobile world and mongrel cities of the early 21st century. What is perhaps even more remarkable is that it seems to be associated with the decline of Enlightenment ideas of rationalism, truth and reality. The “thrown-togetherness” (Doreen Massey’s term) of many newly created places seems to be one expression of the sense that anything goes, that any belief or ideology is valid even if it unsupported by empirical evidence. Hybrid places and heterotopian landscapes are in themselves harmless, and in some ways reflect the diversity and openness of the present-day world that is a consequence of the decline of oppressive, restrictive practices that masqueraded as rational and realistic. However, they are not incidental superficial phenomena so much as manifestations of confusion associated with the paradigm shift that is happening at the end of the rationalist era that has lasted several centuries, confusion that is being reinforced by the emergence of social and political forces that deny evidence, resist diversity and promote exclusion.

The most intense example of heterotopia may be the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. The ruined building was remarkably left standing at the epicentre of the atom bomb explosion. It is a World Heritage Site that preserves destruction and reasserts the continuity of place, yet is also the place where rational knowledge reached beyond reason.

The most intense example of heterotopia may be the Hiroshima Peace Memorial. The ruined building was remarkably left standing at the epicentre of the atom bomb explosion. It is a World Heritage Site that preserves destruction and reasserts the continuity of place, yet is also the place where rational knowledge reached beyond reason.

The Openess of Place

Though there are no obvious guidelines to help make sense of what is happening as rationalism loses its once privileged position, I think a phenomenological return to place offers possible clarifications in a way that is neither poisoned by the confirmation biases of exclusion nor coldly detached. What I mean by a phenomenological return not only considers the importance of belonging somewhere, but, in the present-day context, also attends to flows of information, mobility and heterotopia. More specifically it has to consider the constant interconnections between here and elsewhere that are an unavoidable aspect of current place experiences. Jeff Malpas refers to place as an “open, cleared yet bounded region in which we find ourselves gathered together with other persons and things, and in which we are opened to the world and the world to us.”

The increased openness of place has eroded the distinction between place and placelessness. One response to this is an attempt to reverse change and deny difference; this is a retreat into parochialism and exclusion that are manifestations of a poisoned sense of place, and it has been exacerbated by the echo chambers of social media. The other response embraces openness and diversity, and recognizes that local and global connections are present everywhere. From this perspective every place is a portal to the world. This is implicit in multi-centred lives, time-space compression, and the global village. It is increasingly how people everywhere connect with geography. It regards heterotopia as positive even if its manifestations are baffling. Above all it acknowledges that humanity is shared regardless of local differences.

An everyday instance of the openness of place. A sign in the small town of Sidney in British Columbia for LaLoCa, a store that sells products, according to the small print. “Products from ethical social enterprises and fair trade producers from Vancouver Island, BC & around the world.”

Responsibility and the Future of Places

The social and technological changes of the last fifty years which have affected place and place experiences will not be undone in the foreseeable future. We have moved far beyond the world before modernism in which the distinctiveness of places arose from rooted and geographically separated communities. Distinctiveness is now based partly on the protection of cultural, built and natural heritage defended by forceful international, national and local organizations, partly on place branding and placemaking that have become entrenched in business and planning practices, and partly on what people with multicentred lives bring to the places where they currently live. And not least because of these new commitments to distinctiveness it is inconceivable that there will be an untrammelled revival of the modernist placeless predilection for replacing whatever was old with something efficient and new, though principles of international uniformity will continue to be manifest in landscapes of skyscraper offices, production plants, distribution centres and non-places associated with the global economy.

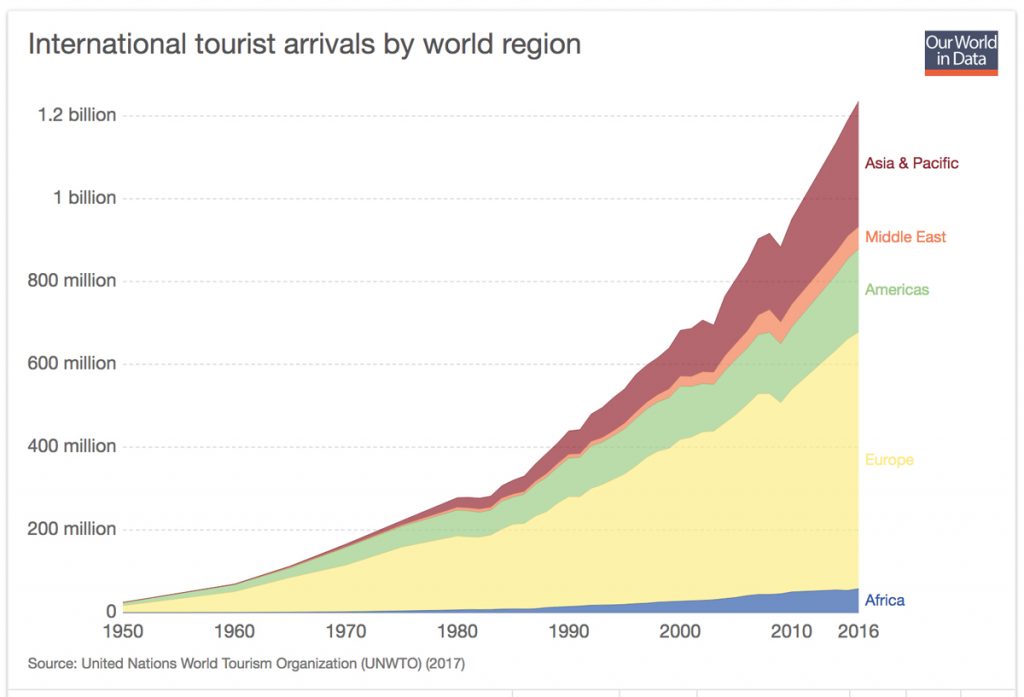

Mobility, whether for tourism or migration, is expected to increase substantially in the coming decades. Cities will continue to hybridize, electronic communications will intrude further and in devious ways into place experiences, heritage preservation and branding will further reinforce distinctiveness. The specific consequences of these trends will vary in intensity and character from place to place and over time. From the perspective of those who consider mobility, multi-centred lives and electronic communications as processes that diminish sense of place and erode rootedness, this is regrettable. My own view is that while these irreversible changes have may have diminished lifelong rootedness in place, they have actually reduced the prevalence of placelessness and have broadened experiences of the diversity of places. They are not without their problems, such as the inconsistent uses of the idea of heritage, the fact that place branding is an indication of submission to neo-liberal economics, the way tourism sometimes overwhelms cities, and electronic media can facilitate exclusionary, parochial attitudes. Nevertheless, on balance I regard the changes a positive trade-off because both because they mostly reinforce place identities and especially because they foster a sense of the openness of place, the understanding that places are portals to the world.

The importance of the openness of place lies in the ways it directly informs how we can understand and take responsibility for places. First, in this ‘post-truth’ age our direct experiences of place allows us to compare the claims and opinions of politicians and supposed experts against what we encounter ourselves – actual people and real things, not ‘the public’ and consumer goods. Second, in a multi-centred mobile world we need to take responsibility for where we are, no matter how briefly we are somewhere. This can happen in countless different ways – gardening, helping neighbours, buying local produce, participation in community activities, and protesting developments that are socially or environmentally damaging. Third, openness to the world is of fundamental significance in understanding the profound challenges of the global village we all now live in, perhaps most significantly, the challenge of climate change, but also water shortages, intensifying social inequality, and the rise of exclusionary authoritarian governments.

Michel Foucault 1970 The Order of Things, (London: Tavistock Press). p.xv.

Jeff Malpas, 2006, Heidegger’s Topology: Being, Place, World (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press), p.221.

Doreen Massey 2005 For Space (London: Sage Publication), Chapter 13

On the other hand mass tourism is a mixed blessing for those places that are on its receiving end, where sheer numbers are beginning to undermine the very place qualities that made them attractive. Venice is perhaps the most extreme example, where the dwindling resident population of about 55,000 is confronted annually by about 25 million visitors, many from cruise ships, but Barcelona, hiking trails in New Zealand and many World Heritage sites, such as the Pantheon in Rome, shown here in 2017, are confronting the same problem of authentic place qualities being eroded by sheer numbers of visitors.

On the other hand mass tourism is a mixed blessing for those places that are on its receiving end, where sheer numbers are beginning to undermine the very place qualities that made them attractive. Venice is perhaps the most extreme example, where the dwindling resident population of about 55,000 is confronted annually by about 25 million visitors, many from cruise ships, but Barcelona, hiking trails in New Zealand and many World Heritage sites, such as the Pantheon in Rome, shown here in 2017, are confronting the same problem of authentic place qualities being eroded by sheer numbers of visitors.