I have been prompted to write about placemaking partly because the Official Community Plan of the City of Victoria in British Columbia, where I have recently moved, devotes a substantial section to “Placemaking – Urban Design and Heritage”, and partly because a recent article in the Guardian about gentrification refers to placemaking not in its usual positive sense, but pejoratively, as a tool used by developers to attract the creative class to potential urban villages that displace relatively poor populations. [There is, by the way, inconsistency in whether place-making is hyphenated. I prefer it without.]

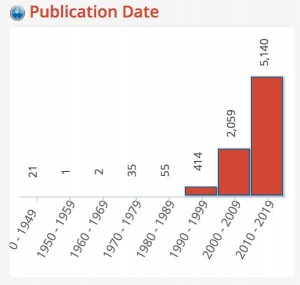

I have read a number of books and articles about placemaking, but unsystematically, and mostly published before 2005. However, when I looked up placemaking in the University of Toronto Library search engine over 7500 books and articles were listed, along with this intriguing bar graph showing numbers of publication by decade (this recent explosion in number of publications is not the norm for every topic – I checked). The recent growth is daunting, so what I will do in this post is to examine the origins and early development of the idea. I haven’t been able to find the publications before 1970 and comments on more recent stuff will have to wait.

I have read a number of books and articles about placemaking, but unsystematically, and mostly published before 2005. However, when I looked up placemaking in the University of Toronto Library search engine over 7500 books and articles were listed, along with this intriguing bar graph showing numbers of publication by decade (this recent explosion in number of publications is not the norm for every topic – I checked). The recent growth is daunting, so what I will do in this post is to examine the origins and early development of the idea. I haven’t been able to find the publications before 1970 and comments on more recent stuff will have to wait.

The current popularity of placemaking revealed in the name of this New Zealand chain of home improvement stores.Whakatane, 2014.

Origins

It’s not clear where or when the idea of placemaking arose, or who first used it. Wikipedia says it is a term that came into use by architects, planners and landscape architects in the 1970s, and that the idea derived from the work of Jane Jacobs and W.H. Whyte. This is the claim of the Project for Public Spaces (mentioned in the last section of this post), and while it is consistent with the view that PPS advocates, as far as I know neither Jacobs nor Whyte wrote explicitly about placemaking. Indeed, the first book with the word in the title that I have found is an archaeological study by George Andrews, published in 1975: Maya Cities: Placemaking and Urbanization, Andrews uses the word to mean simply the founding of settlements.

I was recently reminded that in Place and Placelessness (1976, pp.67-78) I wrote explicitly about placemaking in terms of how distinctive places are made, and on what grounds these might be considered authentic or contrived. Authentically made places arise when the physical, social, aesthetic and spiritual needs of a culture are adapted to particular sites, and this can happen unselfconsciously through vernacular practices, or selfconsciously through thoughtful design; contrivance is when identities are invented or imposed. I suspect I borrowed the word ‘placemaking’ from someone else, but I didn’t identify any specific source. And to the extent that this section of my book attracted any attention, it was authenticity and not placemaking that interested critics.

Five Different Early Approaches to Placemaking

Implicit Placemaking in The Timeless Way of Building: Christopher Alexander’s 1979 book The Timeless Way of Building is about qualities inherent in vernacular architecture, and how the ability to create these qualities might be recovered. His book is, however, implicitly about placemaking. “It is not essential that each person design or shape the place where he is going to live or work,” he wrote. “Obviously people move, are happy in old houses…It is essential only that the people of a society, together, all the millions of them, not just professional architects, design all the millions of places.” This, he suggested, can be achieved through the development what he called “a pattern language,” a design approach he explicated in several subsequent books.

Explicit Placemaking and Community Identity: In the late 1980s the planner Dolores Hayden began to study the mostly suppressed cultural histories of ethnic minorities and women in Los Angeles, and their possible value for a concept of historic preservation that she discussed to in her 1988 paper in the Journal of Architectural Education 41 (3), 45-51 “Placemaking, Preservation, and Urban History” . “Places make memories cohere in complex ways,” she has suggested, but 5,140 5,memories also make places cohere and the formal recognition of these places through restoration and preservation can be powerful ways to reinforce community identity.

Explicit Placemaking in Archeological Contexts: Placemaking: production of built environment in two cultures, by David Stea and Mete Turan in 1993, defined placemaking as being about the context of built form and the production of architecture and settlement. Their interest, which continued the archaeological notion of placemaking first used by Andrews, was in the generative forces and purposes of ordinary building activity in abandoned settlements in Cappadocia in Turkey and of the Anasazi in New Mexico.

Explicit Placemaking in Planning and Design: Much of the current enthusiasm for placemaking seems to stem from Lynda Schneekloth and Robert Shibley (eds) 1995 Placemaking: the art and practice of building communities. This was the first book to consider both the idea and the practice of placemaking at length and with reference to community-based approaches to planning and design.

An illustration taken from Spotify illustrating the community approach to placemaking as employed by Project for Public Spaces

The authors gave placemaking a broad definition (p.1) as “the way all of us as human beings transform the places in which we find ourselves into places in which we live. It includes building and tearing buildings down, cultivating the land and planting gardens, cleaning the kitchen and rearranging the office, making neighborhoods and mowing lawns, taking over buildings and understanding cities.” Placemaking is sometimes invisible and sometimes dramatic. It includes everything from everyday acts of maintenance, renovation and representation, to exceptional events such as moving into a new house or master planned developments.

Their book is based on four case studies (two were in Roanoke) in which architects and planners had recognised the importance of place, and treated placemaking as a community based approach to design. Schneekloth and Shibley put these into a conceptual context. “Each act of placemaking,” they wrote (p.191)., “embodies a vision of who we are and offers a hope of who we want to be as individuals and as groups who share a place in the world.” The tasks of placemaking are therefore inherently political and moral acts, and if they are poorly conceived, the authors noted, placemaking can actually result in destruction of people and places.

A capitalist view of placemaking. I took this photo of a sign in Melbourne airport in 1985.

Placemaking as Place Production and Reproduction: The Marxist geographer David Harvey devoted considerable attention to place in his 1996 book Justice, Nature and the Geography of Difference. He wrote about place production (which he also refers to as place construction and place formation, though he rarely used the word placemaking). He drew on the novels of Raymond Williams to argue for a dialectical conception of places as being “received, made and remade,” rather than fixed entities (p.29-34). And he argued that it is the activity of place construction and production that allows us to achieve a sense of belonging somewhere.

For Harvey place production/placemaking is a social process that has momentum, meaning and political-economic implications. It is a process of carving out relative permanences that are nevertheless always subject to change, dissolution and replacement.

Anthropologist Arjun Appadurai made much the same point in Modernity at Large (1996), though he referred to it as the production of locality. Locality, he suggested, is reproduced in neighbourhoods, and requires hard and repeated work to produce and maintain, work that requires deliberate, risky and even destructive actions.

Placemaking since 2000

Of these five early approaches to placemaking it is, I think (admittedly without having read a substantial sample of recent literature), the community-based design approach to placemaking that has taken off, though the other ideas are not entirely dormant. For example, David Seamon and others have linked Alexander’s ideas to a phenomenological interpretation of place, and his ideas have been translated into practice by architects such as Gary Coates. Hayden’s proposals for placemaking through recognition of the importance of place for disadvantaged communities seems to have been translated into the use of artworks for placemaking. See for instance Rhona Warwick’s 2006 book, Arcade: Artists and Placemaking, which is about the importance of artwork in former slums in Glasgow.

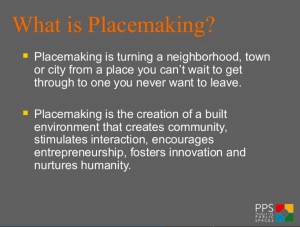

Notwithstanding these, placemaking now usually seems to refer to community-based design of small urban spaces. This is especially apparent in the work of the influential consulting group, Project for Public Spaces. Their website is replete with discussions and suggestions:

- “Placemaking is both an overarching idea and a hands-on tool for improving a neighborhood, city or region. It has the potential to be one of the most transformative ideas of this century.”

- “Placemaking is the process through which we collectively shape our public realm to maximize shared value. Rooted in community-based participation, Placemaking involves the planning, design, management and programming of public spaces…Placemaking is how people are more collectively and intentionally shaping our world, and our future on this planet.”

- “It takes a place to create a community, and a community to create a place.”

Here are two images from the PPS website:

More generally, urban designers and planners almost everywhere seem have adopted the idea of placemaking as a key aim of their work (see for example, Carmana and Tiesdell (eds) 2006 The Urban Design Reader, the publications of CABE (Centre for Architecture and Built Environment) in the UK, the City of Victoria Official Community Plan), though the emphasis on community engagement is variable and the usual impression is that placemaking is always a good and positive practice. A more critical notion of place production and reconstruction nevertheless sometimes rises to the surface, as in the 2010 book The Placemaker’s Guide to Building Community by Nabeel Hamdi, who once worked for the GLC on social housing. In it he writes (p.222): “We now recognise that there will always be limitations to community participation and good governance, given the networked rather than place-based structure of community in cities, and given the persistence of unequal power relations and corruption locally, nationally and globally.” And Dylan Trigg, in his 2012 book The Memory of Place suggests an entirely different notion of placemaking as a personal act that involves self-awareness of experiences and memories of somewhere, and in which imagination is an act of placemaking for the future.

A Final Cautionary Note – mostly copied from my post on Non-Place/Placelessness

• Unmaking of Place (or placeunmaking). This infrequently used term is, I think, invaluable as a caution about placemaking – best laid plans too often go awry. Jame Kalven, who spent many years working and placemaking in public housing projects in Chicago, uses it to describe the consequences of the Plan for Transformation in which the city demolished projects in order to make places supposedly better but which were, in his view, an assault on the identities of those for whom these doomed places were home. The transformation was, in a sense, the polar opposite of preservation and placemaking.

The fact is that all placemaking is a process of creative place destruction, replacing an existing place with one that is thought to be an improvement. Those whose places and communities are being replaced, even if they are in aging standardized apartment towers that were the products of clean-sweep renewal, are unlikely to regard it positively, especially when it is part of the planning toolkit used by developers to create urban villages that promote gentrification.

The image on the left is from

The image on the left is from  •

•